Baltimore’s civil rights movement changed dramatically during the 35 years between the beginning of the Great Depression in October 1929 and the federal legislative victories of the mid-1960s. Education and criminal injustice were two of the most significant areas of organizing and advocacy during this period. For Baltimore’s segregated Black schools, the 1921 Strayer Report had prompted only limited improvements to the frustration of students and families. But, the NAACP’s legal strategy on school segregation in Maryland began to yield results in the 1930s by winning the admission of Donald Murray to the University of Maryland and the equalization of Black and white teacher salaries statewide. The 1930s also saw a renewed mass movement of Baltimore residents calling for national anti-lynching legislation and organizing against police violence. These varied efforts culminated in the 1942 March on Annapolis—the first mass demonstration for civil rights at the state capital.

After the end of World War II in 1945, a local interracial student movement, largely led by students from Morgan State College, waged a disruptive and highly visible campaign to overturn decades of segregationist policies. The rhetoric of American democracy and postwar consumer politics were powerful tools for Black activists who used sit-ins, picket lines, and boycotts to attack Jim Crow policies at parks, pools, recreational facilities, and consumer spaces, such as lunch counters, restaurants, and department stores in the 1940s and 1950s.

The 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education opened even more opportunities for Black Baltimoreans to challenge Jim Crow policies in Baltimore City and across the state of Maryland. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination in education, employment, and public accommodations, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting, were the result of decades of organizing and advocacy in Baltimore and in communities around the country.

These revolutionary changes were consistently accompanied by white reaction and opposition—including resistance to the construction of public housing in segregated white neighborhoods in the 1940s, white students and families protesting school desegregation in the 1950s, and white voters fighting against open housing in the 1960s. White liberals, including Mayor Theodore McKeldin, struggled to respond to this opposition even as it limited the scope and effectiveness of many efforts to reduce racial inequality in the decades to follow.

Freedom and the New Deal: 1929–1941

For Black Baltimoreans already burdened by employment discrimination and segregated housing, the national economic crisis following the “Black Tuesday” stock market crash on October 29, 1929, brought widespread job loss and even deeper poverty. Decades of legal and political advocacy by the Brotherhood of Liberty, Maryland Suffrage League, and others prevented the mass disenfranchisement found in other Southern towns and cities. But, despite efforts by the new local branch of the NAACP, discriminatory policies and racial prejudice by white leadership frustrated the ambitions of Black Baltimoreans seeking equal treatment by city, state, or private employers. The Afro-American neatly summarized local conditions in 1933 when the paper labeled Baltimore a “border city with Southern feelings.”1

From the outset of the Great Depression and through the beginning of World War II, Black residents responded to these challenges with a renewed campaign of protest, fighting for fair administration of criminal justice, equal employment, and equal access to education. Black activists had some support from white neighbors, including communists, progressive reformers, and, after 1935, labor organizers with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), who were seeking better working conditions and more equitable hiring.2 The years between 1930 and 1934, historian Andor Skotnes argues, were “a particularly fluid and experimental period during which various groupings” of both labor and freedom movements “worked closely together.”3

Young Black people, frustrated by the difficulty of finding work in the early years of the Great Depression, played a key role in the renewal of the local movement. In October 1931, two sisters, 18-year-old Juanita and 21-year-old Virginia Jackson, responded to the shortage of jobs by organizing the City-Wide Young People’s Forum at Sharp Street Church at Dolphin and Etting Streets. Famed Black educator and activist Nannie Helen Burroughs later called the Forum, “the best, most progressive, and analytical organization of Negro young people in America. It feels, thinks, believes, acts.”4

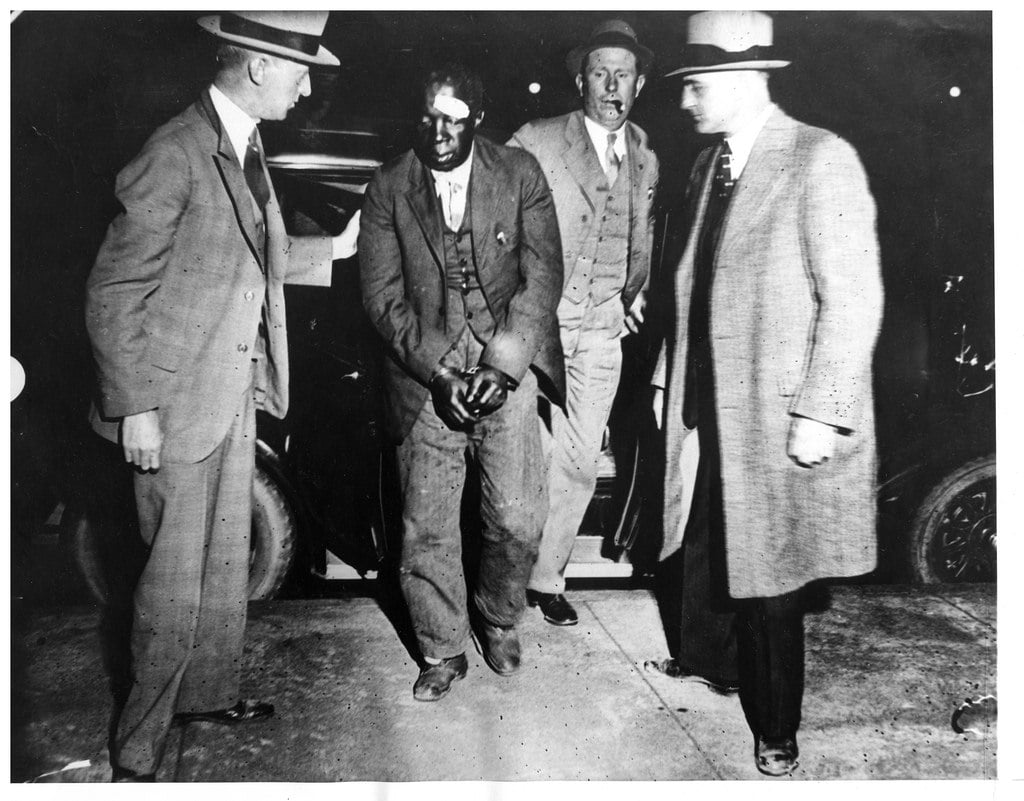

Around the same time, a series of brutal lynchings pushed residents toward more radical activism and encouraged the growth of a mass movement. The 1932 trial and 1933 execution of Euel Lee led to major protests over inequitable sentencing and inadequate protection for Black defendants.5 The brutal lynching of George Armwood on October 18, 1933, following his transfer from the Baltimore City jail to Princess Anne, the seat of Somerset County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, horrified but did not surprise Black Baltimoreans. The attack galvanized Black support for proposed federal anti-lynching legislation.6 Communists were among the most visible white allies in the defense of Euel Lee and the response to Armwood’s murder, with attorney Bernard Ades and the International Labor Defense, a legal advocacy organization associated with Communist International, taking a prominent role in Lee’s defense and in related anti-lynching activism.7

Participants in the City-Wide Young People’s Forum used a broad array of tactics—public meetings, letter-writing campaigns, newspaper editorials, and picket lines—to pressure elected officials and business owners to change discriminatory policies. Leveraging the group’s popularity, in September 1933, Juanita and Virginia’s mother, Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson worked with 25-year-old lawyer Thurgood Marshall and others to recruit hundreds of young people to picket businesses on the 1700 block of Pennsylvania Avenue that refused to hire Black workers. A successful lawsuit by business-owners barred further protests and brought this “Buy Where You Can Work” campaign to an abrupt end. Fortunately, the campaign on Pennsylvania Avenue resulted in a new relationship between Lillie Carroll Jackson and the Baltimore NAACP branch. With encouragement from Afro-American newspaper editor Carl Murphy and attorney Charles Hamilton Houston, Jackson took over as the president of the branch in 1935 and remained in that position for 35 years.8

While Jackson, Murphy, and other leaders associated with the local NAACP were among the most visible advocates of civil rights for Black Baltimoreans, the organization also relied on a large number of less well-known individuals who gave money or volunteered time to support the group. Without any paid staff, the branch relied on supportive neighbors and volunteers to fill roles such as the board secretary, a position most often held by women before 1935. For example, between 1930 and 1934, the branch secretary was Mary Cook who lived at 1422 McCulloh Street—just a few blocks away from Jackson and the Sharp Street Church.9

World War II and the “Double V” Campaign: 1941–1954

The beginning of World War II in Europe in 1939 and the United States’ declaration of war in response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 prompted the formation of new coalitions opposed to Jim Crow discrimination and segregation. For Black residents facing high rents for rooms in overcrowded houses and brutal unjust policing in the city’s segregated Black neighborhoods, the need for change was clear. Afro-American editor Carl Murphy joined other Black newspaper editors and activists in pushing the “Double V” campaign seeking victory over fascism in Europe and victory over injustice at home in the United States. In editorials and reporting in their local and national editions, the newspaper labeled Jim Crow segregation and discrimination as “Hitlerism” in a fight to influence public opinion.10

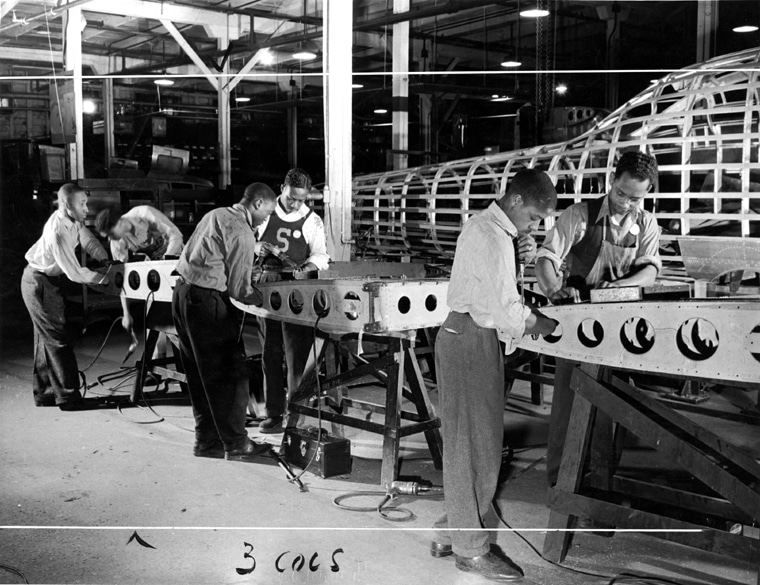

By the end of the 1930s, Baltimore activists with the local NAACP, the Baltimore Urban League, and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) worked in concert with a growing national alliance dedicated to the rights of workers and Black Americans. In December 1940, the CIO and partners launched a campaign to force the Glenn L. Martin Company in Baltimore County, one of the region’s largest wartime defense contractors, to begin training and hiring skilled Black workers. The campaign, linked to the March on Washington Movement organized by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, pushed President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 8802 on June 25, 1941—less than a week before the scheduled march in Washington, DC, The order prohibited discriminatory hiring in wartime industries and established the Fair Employment Practices Commission to enforce the new law. Thirty-year-old Clarence Mitchell, who had reported on George Armwood’s lynching for the Afro-American in 1934, joined the new commission as the associate director of field operations. By October 1941, local activists had succeeded in forcing the Martin Company to meet their demands.11

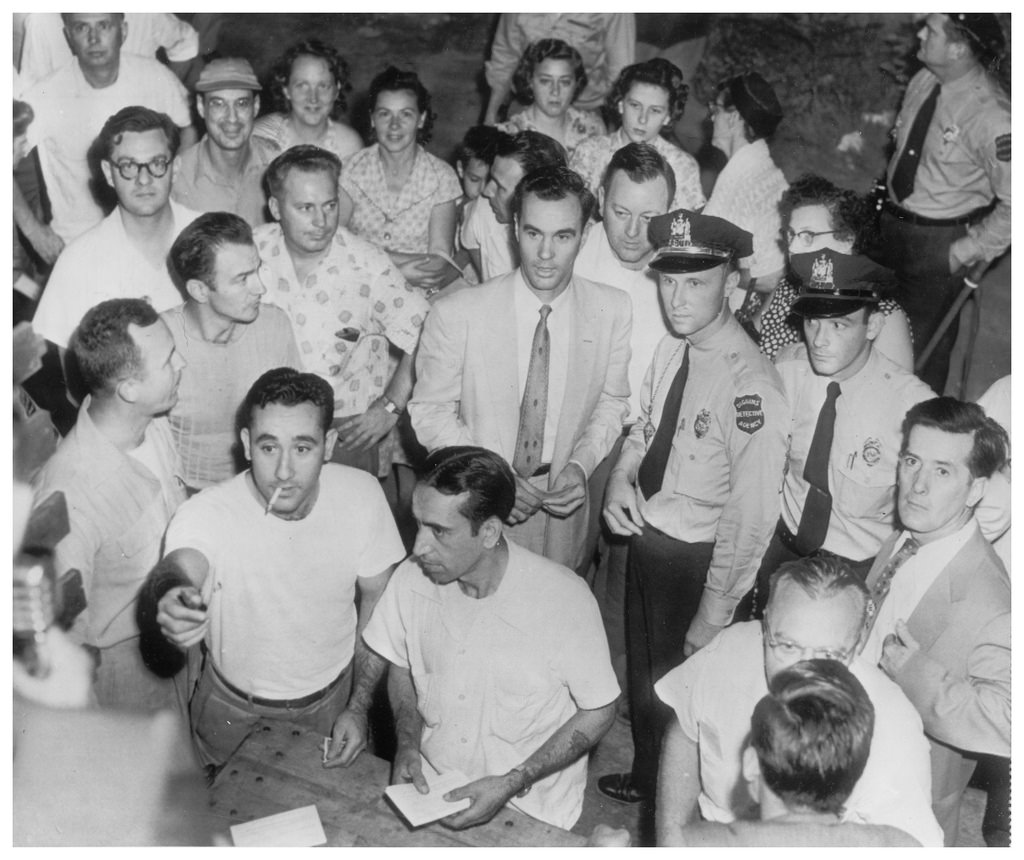

The power of the city’s unified Black community was most clearly illustrated by the March on Annapolis in 1942. On February 7, 1942, a Baltimore City police officer shot and killed Thomas Broadus, a Black US Army private from Pittsburgh. Outraged by the attack, the Asco Club, a local Black social organization, appointed Dr. John E. T. Camper, a Black physician, to seek help from Lillie C. Jackson and the Baltimore NAACP to investigate the killing. The organizers built on the momentum of the March on Washington Movement established by A. Phillip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car porters. Randolph had called off the planned march after President Roosevelt signed the executive order prohibiting discrimination in the defense industry—but Broadus’ death gave Baltimoreans a new reason to assemble.

Jackson, Camper, and other activists formed the Citizen’s Committee for Justice, chaired by Dr. Carl Murphy, and planned a march to protest the mistreatment of Black residents by Baltimore police officers. Dr. Camper, who was also a World War I veteran, later recalled:

I got fighting mad when I found how little the rights of colored people are respected, even by the law which is designed to protect them… and what’s more I’ve been mad ever since.12

Criminal injustice and police brutality affected Black Baltimoreans from a wide range of religious and professional backgrounds. The close proximity of individual activists played a role in enabling their quickly coordinated response. Dr. John E. T. Camper lived at 639 N. Carey Street, just a few blocks west of Providence Baptist Church, whose pastor, Rev. E. W. White, served as secretary to the Citizen’s Committee. Lillie C. Jackson’s home at 1226 Druid Hill Avenue doubled as offices for the Citizen’s Committee and the NAACP. Edward S. Lewis, executive secretary of the Urban League, lived at 1538 Division Street and worked out of an office at 1841 Pennsylvania Avenue.

On April 24, 1942, over 2,000 people rode charter buses, drove, and even walked from Baltimore to the State House in Annapolis for a hearing with Governor Herbert R. O’Conor. Voluntary contributions of $800 covered the transportation costs for the people traveling to Annapolis and the crowd gathered with a reportedly “serious, sober attitude.”13

Much of the testimony focused on criminal injustice and Baltimore police misconduct. Edward S. Lewis explained how Baltimore Police Commissioner Robert F. Stanton had ignored the “repeated efforts of citizens… to initiate preventive crime measures.” Rev. E. W. White, a recent president of the Interdenominational Ministers’ Alliance, described how “colored people in Baltimore are inadequately and unjustly policed” and asked Governor O’Conor to appoint “colored policeman in uniform.” Lillie C. Jackson echoed White’s message in asking for “appointment of another colored policewoman” (the police hired the city’s first Black non-uniformed police officer, Violet Hill Whyte, in July 1937). W. A. C. Hughes Jr., attorney for the NAACP, sought an investigation of police killings in Baltimore. Linwood G. Koger, an attorney, World War I veteran, and head of the Walter Green Post of the American Legion, asked the Governor to appoint a “colored magistrate.” Donald Boyce, 10th Ward Committeeman for the Republican City Committee, asked directly for the removal of Police Commissioner Robert F. Stanton.

The speakers didn’t limit their remarks to criminal injustice. Rev. George A. Crawley, leader of St. Paul Baptist Church and president of the United Baptists of Maryland, who lived at 1418 E. Biddle Street, asked for “all colored staff and membership on [the] board of the Crownsville State Hospital for Insane,” which had been established as the Hospital for the Negro Insane of Maryland in 1910. Dr. Ralph Young, who lived at 1429 E. Monument Street, asked for Black participation on the Maryland Tuberculosis Commission, telling the Governor “we need to have a part in administration of our own institutions.” Carl Murphy testified on discrimination in the defense industry; Mrs. Virgie Waters, president of the Beauticians’ Association, “urged representation on the State board” regulating beauticians; and, 21-year-old Harry A. Cole, a junior at Morgan College and later the first Black person elected to the Maryland State Senate, simply “spoke for youth.”14

The March on Annapolis was the largest freedom demonstration in Maryland history and it led Governor O’Conor to appoint the statewide Commission on Problems Affecting the Negro Population to consider the protestors’ concerns.15 The organizing abilities and financial support on display at the Maryland State House (AA-685) helped make Baltimore’s civil rights movement “increasingly grassroots in character” during the late 1930s and early 1940s.16 Frustration with O’Conor’s limited response to the protest prompted activists to invest time and money in extensive voter registration efforts in the early 1940s.

The Baltimore NAACP’s political organizing helped liberal Republican Theodore McKeldin win office as Mayor in November 1942. As Mayor from 1943 to 1947, McKeldin lent his support to many long-sought demands by Black Baltimoreans. For example, in March 1944, Mayor McKeldin appointed George McMechen, NAACP activist and attorney, as the first Black person to serve on the Baltimore school board.17 Unfortunately for his supporters, McKeldin’s first campaign for Maryland Governor in 1946 was unsuccessful. McKeldin’s opponent, Governor William Preston Lane Jr. had served as the state attorney general when a group of white Marylanders lynched George Armwood 13 years earlier and did little to change the state’s approach to civil rights as governor.

After World War II ended in 1945, the landscape of race and activism began to quickly change as Black residents started to buy homes in formerly segregated white neighborhoods west of Fulton Avenue. The 1948 US Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer made the deed restrictions keeping out Black residents unenforceable and the crowding in segregated Black neighborhoods made Black households more willing to risk the antagonism of white neighbors in order to buy a home for their family.18 At the same time, suburban developers began to build huge numbers of new homes in Baltimore County with support from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Only white households could access FHA mortgages to purchase houses in these suburban neighborhoods.

Despite these challenges, young people again led the attack on segregation in Baltimore with a new commitment to using direct action and civil disobedience to advance their cause. In the 1940s, Black and white teenagers undertook a series of protests over segregation at parks and recreational facilities.19

In February 1947, Black students from Morgan State College began protesting the segregated seating at Ford’s Theatre on Fayette Street—launching what became a sustained multi-year campaign by the Baltimore NAACP, including picket lines, actor and audience boycotts, and political pressure by local elected officials.20 Ford’s Theatre allowed Black actors to perform on stage but offered Black patrons segregated seating in an area known as “the pit” due to the limited view of the show. Black theater patrons could purchase tickets at the theater’s main window if they were willing to then, walk around to the alley, climb a three-story staircase, and find a seat in the last few rows of the second balcony. The Lyric Theatre (B-106), in comparison, maintained the opposite policy where the theater prohibited Black performers from their stage, but allowed general seating.

In an effective early local use of nonviolent direct action, between 1953 and 1954, the local chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Baltimore Urban League, and Americans for Democratic Action organized a campaign protesting segregated lunch counter service at the Kresge, Schulte United, Woolworth, and McCrory’s “five-and-dime” stores on the 200 block of W. Lexington Street. In January 1955, students from Morgan State College joined CORE in nonviolent sit-ins at the Read’s Drug Store at Howard and Lexington Streets and at a second location in Northwood Shopping Center and successfully ended the chain’s policy of lunch counter segregation.21

Local activists continued to push the city to begin desegregating schools and other public facilities under Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., who served as mayor from 1947 to 1959. For example, in August 1951, a lawsuit by the Baltimore NAACP against the school board opened a limited set of classes at Polytechnic High School to Black students.22 In 1950, Governor Lane survived a bruising primary challenge by Democratic candidate George P. Mahoney (running on an anti-tax platform) but lost to Theodore McKeldin in the general election.23 Between 1951 and 1959, Governor McKeldin again delivered for Black supporters by establishing the Commission on Interracial Problems and Relations in 1951 and ending segregation at most state parks in 1953.24 In 1953, Governor McKeldin directly urged the owners of Ford’s Theatre to end their segregated seating policy. The theater reversed their policy and brought the years-long protest campaign to an end. C. Fraser Smith observes that while Governor McKeldin "deserved the ceremonial accolade" when he won a 1953 award from the local Hollander Foundation recognizing his role, "no-name workers had done the heavy lifting" in desegregating the theater.

Moreover, the slow and incremental pace of change represented by the desegregation of Ford’s Theatre could not be sustained long. The Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision and an increasingly active student movement brought new pressure on elected officials to dismantle Jim Crow policies in Maryland much more quickly.

Brown in Baltimore: 1954–1965

On May 17, 1954, the US Supreme Court announced its decision in Brown v. Board of Education, ruling that separate but equal schools were unconstitutional. The ruling essentially overturned Plessy v. Ferguson and established a new legal foundation for the modern civil rights movement. The pace of school integration after the ruling varied widely across the country. Unlike many other Southern cities and other jurisdictions in Maryland, the Baltimore school board, chaired by Walter Sondheim, responded quickly to the decision by announcing a plan to end legal segregation. The city continued the long-standing policy of “open-enrollment” (where any student could attend any school) but simply dropped the requirement that Black students attend segregated “colored schools.” For Lillie C. Jackson and members of the Baltimore NAACP, the decision held the promise of a revolution. On June 11, 1954, Jackson shared her response to the ruling in a letter Gloster Current, long-time director of branch and field services for the national NAACP: “We are all Americans and the Jim Crow must go.”25

Within a few short years, the US Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the Civil Rights Act of 1960, to protect federal voting rights and prohibit discriminatory voting rules. While the 1957 bill was famously filibustered by Democratic Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, all of Maryland’s Senators and Congressional Representatives voted in the bill’s favor.26 When President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the 1957 law, it was the first civil rights bill since Reconstruction. The law created the US Commission on Civil Rights that—while initially limited to fact-finding—played a key role in documenting injustice around the country.

Locally, students continued to take the lead on civil-rights activism. In late April and early May 1955, after a series of student protests, involving hundreds of Black students from Morgan State College and white students from Johns Hopkins University, Douglas Sands, a prominent student activist and the president-elect for the Morgan State student council split the Social Action Committee of the Morgan State Student Government Association and formed an independent organization known as the Civic Interest Group (CIG).27

Outside of Maryland, the student-led nonviolent protest movement achieved a new national prominence following the sit-in protests in Greensboro, North Carolina, and the subsequent formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in April 1960. This example illustrates the importance of training and information sharing within the movement in this period. A later oral history suggests a publication documenting the success of Morgan State students and Baltimore CORE members in using sit-ins to protest segregation at lunch counters on Lexington Street in the 1950s inspired Greensboro activist George Simkins Jr. to reach out to CORE field secretary Gordon Carey to come to North Carolina and help support the student protestors.28

On March 15, 1960, student activists from Morgan State College, Johns Hopkins University, and Goucher College with CIG launched a new campaign against segregated restaurants. As many as 300 students participated in the first week of protests at the Rooftop Dining Room, at Hecht-May’s department store, and at the Northwood Theatre adjacent to Morgan’s northeast Baltimore campus. On March 26, the protests moved downtown as teams of Morgan State students targeted four downtown department store restaurants around the intersection of Howard and Lexington Streets: Hecht-May, Hutzler’s, Stewart’s, and Hochschild Kohn. By May 1960, the campaign had resulted in the integration of 12 previously segregated downtown restaurants.29

The next year, in 1961, after embarrassing incidents of discrimination against African diplomats at restaurants along US Route 40 in Maryland and Delaware, the national organization of CORE saw an opportunity. CORE recruited local volunteers from CIG and several other organizations for the “Route 40 Project,” which would challenge the segregated facilities in a massive “Freedom Ride” on November 11, 1961. Just days before the ride began, however, 47 restaurants along Route 40 agreed to desegregate due to both the threat of protests and pressure from President John F. Kennedy’s administration. CORE called off the ride but sent the volunteers gathering at DC’s Howard University to Baltimore instead where they picketed some of the city’s segregated restaurants.30

CIG continued to organize and, two years later, in July 1963, Black and white students and activists came to the Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Baltimore County to demand the business integrate. Activists had protested the park’s segregated admission policy for around a decade, but the July protests organized by CIG, CORE, the NAACP, and the National Council of Churches (NCC) brought more pressure than ever before. On July 4 and July 7, Baltimore County police arrested nearly 400 protestors (including nearly two dozen Catholic and Protestant clergy and Jewish rabbis) for trespassing. It took a few months more, but, on August 28, 1963, the park’s owners agreed to a settlement negotiated by then County Executive Spiro T. Agnew ending their segregation policy.31 That same summer, Black church leaders, business owners, and activists also worked to recruit and transport thousands of Baltimore residents to Washington, DC, in support of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. As a generation earlier, Baltimore’s experienced community of activists and proximity to Washington, DC, helped tie the work of local activists into a broader national agenda.

The integration of Baltimore’s businesses and neighborhoods was undermined, however, by white residents relocating in large numbers to the increasingly segregated white suburbs. In 1958, the Maryland State Commission on Interracial Problems observed that Baltimore’s problem “is not with violence” around neighborhood integration, in contrast to other cities like Detroit or Chicago, but with the frigid withdrawal” of white residents.32 Between 1950 and 1960, the population of Baltimore County grew by over 80%, from 270,273 to 492,428 people. In the same 10-year period, Baltimore City lost population for the first time, dropping from 949,708 to 939,024 people. The proportion of Black residents grew from around 24% to 35% in the same period. Between 1960 and 1970, the population of Baltimore County continued to grow, increasing population by another 26%. Similarly, between 1950 and 1970, the population of Anne Arundel County grew by more than 250% jumping from just 117,392 people in 1950 to 297,539 in 1970.

This massive movement of white residents, popularly known as white flight, was directly encouraged and subsidized by housing and transportation policies at all levels of government. Baltimore County zoning prioritized the development of single-family housing developments, often financed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and used zoning to largely exclude the development of more affordable multifamily housing.33 The expansion of federal highways, including the Jones Falls Expressway (I-83), which began development in 1955, and the Baltimore Beltway (I-695), which opened in stages between 1955 and 1962, made it easier for white commuters to move away from the city center to segregated enclaves.34 Baltimore County also resisted the construction of public housing, forcing long-term county residents to seek affordable housing within the city.35

Sixty-two-year-old former Governor Theodore McKeldin took office for his second term as Baltimore’s mayor in 1963—20 years after the start of his first term as mayor in 1942. In June 1966, he spoke directly to white constituents about their apathy towards the limited progress of civil rights in Baltimore:

… while we have moved, we have not moved toward the solution of these problems with the speed and vigor with which we are capable. We have not really attempted, as a community, to understand the plight, the unrest, and the feelings of those who have been denied. We have not attempted to understand why, even after significant progress, our negro brethren still insist that all is not right nor community—that there is much to be done.36

Thirty-five years after the Young People’s Forum formed at Sharp Street Church, 24 years after the consequential March on Annapolis, and 12 years after the Brown decision, Black people in Baltimore continued to struggle for freedom.

Politics and Activism

Black Baltimoreans continued organizing and often worked with labor activists to form political coalitions and alliances. In Maryland, a growing population of Black registered voters, helped elect candidates with greater support for policies that advanced Black civil rights—notably including Theodore McKeldin, who served two terms as Mayor of Baltimore and two terms as governor. Elected officials were also forced to respond to numerous direct-action campaigns organized by Black students in this period. A growing movement sought to hold elected officials and local business leaders accountable to new local and federal requirements for equal rights.

New Deal Democrats and Black Voters: 1930–1940s

In the 1930s, the growing alliance between labor and civil rights activists helped turn electoral politics into a powerful tool for policy change in Baltimore and Maryland. A few months before the 1932 election, the Afro-American helped to organize a registration drive for Black voters, highlighting the fact that in Baltimore City, “37,908 colored people are registered and ready to vote, and 54,000 of us are slackers and ineligible to cast a ballot because we have not registered.”37 The drive was supported by former City Councilmember Walter S. Emerson and leading members of the A.M.E. Church, and local socialist and Communist leaders were invited to participate.38

While the realignment of Black voters from the Republican party to the Democratic party began with the New Deal in the 1930s, Republican candidates in Maryland still sought and won significant support from Black voters. In 1934, Baltimore’s Black voters helped to defeat long-serving Democratic Maryland Governor Albert Ritchie in favor of Republican Harry Nice. During Nice’s term as Governor from 1935 to 1939, Black Republican activist Marse Calloway organized a rally at Bethel A.M.E. Church to push the Governor to promise to appoint Black police officers to the Baltimore City Police Department.39 The Governor offered a limited compromise by directing the department to hire the city’s first non-uniformed police officer, Violet Hill Whyte, a 40-year-old Black educator.

In May 1943, Black voters helped defeat Baltimore’s long-serving Democratic Mayor Howard W. Jackson in favor of Republican Theodore McKeldin. McKeldin’s liberal views on civil rights won him significant support from Black voters, including many registered by the NAACP in the group’s “Vote for Victory” drive.40 As Mayor, and later Governor, McKeldin was accessible to Black activists in a way that no other white elected official in Baltimore had been before. As Rev. Marion Bascom, a civil rights activist and leader of Douglas Memorial Community Church, later noted: “People didn’t have to have a ‘sit-in’ demonstration to see Mr. McKeldin. Mr. McKeldin was available and this, I think, made all the difference.”41

While there was substantial local support for Republicans Nice and McKeldin, who embraced a civil rights platform, ultimately these candidates did not reverse the realignment of Black voters from the Republican to the Democratic Party. Black voters in northern cities were key to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s reelection in 1936.42 Commenting on Roosevelt’s 1936 election, Black mathematician and writer Kelly Miller celebrated the end of the “Solid South” control over the Democratic party and called the election a “victory of liberalism over reaction.” Baltimore’s Clarence Mitchell, however, remained skeptical of the depth of the Roosevelt administration’s commitment to equal rights for Black Americans, observing: “When you start from a position of zero, even if you move up to a point of two on a scale of 12, it looks like a big improvement.”43

In Baltimore, hotel owner Thomas R. Smith was one of the city’s few stalwart Black Democrats in the early twentieth century, and the Smith Hotel was remembered by the Sun, at the time of the building’s demolition in July 1957, as “almost a shrine to much of Baltimore’s Negro population.” Built in 1912, the hotel served as a “gathering place for Negro visitors from as far north as New York and as far west as Chicago.”44

Black Political Power and White Reaction: 1950s–1960s

The success of Black voters in exerting pressure on elected officials built organizing capacity that helped lead to the election of Black elected officials in the 1950s and 1960s. On September 15, 1942, Linwood Koger was the first Black candidate to win a Republican primary election for the State Senate in the Fourth Legislative District—thanks to the support of a political organization led by Marse Callaway.45 In December 1946, Victorine Q. Adams, later the first Black woman to win a seat on the Baltimore City Council, established the Colored Women’s Democratic Campaign Committee, and, together with the NAACP, organized regular voter registration campaigns in the 1940s.

Harry A. Cole, who had testified at the March on Annapolis in 1942, won a seat in the Maryland State Senate in 1954. In 1958, Verda F. Welcome and Irma George Dixon became the first Black women to be elected to the House of Delegates, and, in 1962, Verda Welcome became the first African American woman to be elected to the Maryland Senate.

But this same period also saw a renewed effort by white elected officials to capitalize on the reaction of white Marylanders who opposed the civil rights movement and sought to maintain the status quo. Thousands of white Baltimoreans in the city and suburbs voted in support of George C. Wallace, the segregationist Democratic Governor of Alabama, in the 1964 Democratic primary for President and for Barry Goldwater, a Republican Senator and opponent of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, in that year’s general election.

Radical Spaces, Students, and Interracial Organizing: 1930s–1960s

The Black student movement that grew between the 1930s and 1960s found supportive mentors and allies in a variety of locations. For example, in the late 1920s, the Communist Party hosted interracial dances at the Monumental Lodge No. 3, Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World, at 1528 Madison Avenue, drawing over 400 people to a dance in 1929. In 1955, teenage members, both white and black, of the regional YMCA held an interracial conference including a session on “Understanding Other Races,” where participants signed on to a statement calling for the end of segregated “separate socials” as a “positive step the Hi-Y and Try Hi-Y can take to help abolish prejudice.”46

One important site for Morgan State University student activists between the 1940s and 1970s was Morgan Christian Center (B-5250), now known as the Morgan State University Memorial Chapel. Designed by Towson-born African American architect Albert Irvin Cassell, the Morgan Christian Center and the adjacent parsonage were built with the intent to sustain the religious roots of Morgan College following the school’s 1939 sale to the state of Maryland. Rev. Dr. Howard L. Cornish, a 1927 Morgan graduate and math professor, became the director of the Morgan Christian Center in 1944. Cornish lived at the parsonage and supported student civil rights activism up until his retirement in 1976.

Students also found space on the Johns Hopkins University Homewood campus for radical organizing. In 1953, Chester Wickwire accepted a position as the executive secretary of the Johns Hopkins University campus YMCA and the chaplain for the university. Using space at Levering Hall on the Homewood Campus, Wickwire provided “a haven for liberals on an otherwise conservative campus” and ran “ran various student life programs such as concerts, dances, and movie screenings while simultaneously organizing political discussions about civil rights, pacifism, the Cold War, and Vietnam.” In the fall of 1955, about a dozen white male students formed the Students for Democratic Action (SDA), affiliated with the Americans for Democratic Action, and started to compile a list of discriminatory policies at Baltimore hotels. The next spring, the group joined SDA chapters around the country in raising money to support the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama.47 Wickwire was an active participant in the civil rights movement and an ally of the SDA and CIG throughout his time at Johns Hopkins University.

Homes, Neighborhoods, and Transportation

Decades of pervasive housing segregation gave Black Baltimoreans few options for affordable, safe, and well-maintained homes or apartments. In the 1950s and 1960s, activists continued to struggle against exclusion in suburban neighborhoods and new challenges as “blockbusting” real estate speculators sought to exploit the Black households that had moved to formerly segregated white neighborhoods. At the same time, highway and urban renewal projects disproportionally affected Black residents, destroying long-established Black neighborhoods and displacing residents. While the combined shifts of white flight and Black displacement transformed the city’s racial geography, by the mid-1960s, housing remained as segregated as ever before.

Redlining and White Flight: 1930s–1960s

The Great Depression, New Deal policies, and World War II all led to major changes in public policies around housing and transportation in Baltimore. At the outset of the Great Depression, the number of new houses built in the US annually dropped by over 90% from a high of 937,000 in 1925 to 93,000 in 1933.48 In Baltimore, a shortage of new homes and widespread job loss led existing homeowners to stay in place and reinforced existing patterns of segregation. A series of federal housing laws associated with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal helped to further reinforce housing segregation in American cities. The federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), established in 1933, created “residential security” ratings, today known as “redlining” maps, that discouraged lending in neighborhoods occupied by Black Americans. Similarly, the National Housing Act of 1934 created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to underwrite loans for building, rehabilitating, and buying houses, but these loans were generally not available to African Americans.49

The Housing Act of 1937 offered new federal funding for cities like Baltimore to engage in “slum clearance” and build new public housing projects. These included Edgar Allan Poe Homes (B-5119, built 1938) and McCulloh Homes (built 1940)—two of the earliest public housing projects for Black Baltimoreans. Poe and McCulloh Homes consist of a series of two- and three-story garden apartment buildings facing open pedestrian-oriented courts making these new residences dramatically different from the small rowhouses that had previously housed poor Black residents. But even with a handful of new public housing projects, the combination of segregation and a growing population moving to Baltimore to work in the defense industry resulted in severe overcrowding. For example, from January 1941 to November 1941 alone, housing vacancies for units open to Black occupancy shrank from .8% to .1%.

While it was rare for private developers to use FHA mortgage insurance for housing complexes for African Americans, one of example exists in eastern Baltimore County. Day Village, a 500-unit, two-bedroom duplex community, opened in 1944 along Avondale Road in Dundalk in response to the high demand for housing for workers at defense industry factories during World War II. Despite being located within the predominantly Black Turner’s Station (BA-3056) community, Day Village faced opposition from the white Dundalk Home Owner’s Association who opposed any housing projects for Black workers. Joseph P. Day, the New York developer behind the project, stated that the project provided “a proper environment for many who have been forced to live in crowded, unsatisfactory conditions.”50 A May 1945 advertisement in the Afro-American stated: “People have flocked to see Day Village. … For the first time real homes in a fine setting are available—no more slums and poor environment.”51 By 1947, the FHA touted the project as “one of the outstanding rental housing projects developed for Negros under the FHA program.”52 Day Village provided higher-quality housing, commercial services and recreational opportunities for its Black residents and likely spurred similar developments nationwide; however, Day Village was ultimately still a segregated Black community. 53

In a letter to Mayor McKeldin in July 1945, in response to the efforts by a group of 350 residents in the Fulton Avenue area to prevent Black residents from moving west, the NAACP argued “growth demands that we take in those streets that fringe our area since every attempt to enter new sections is vigorously denied.” The Citizens Committee for Justice and the Baltimore Urban League observed “the need for more housing is most sharply felt in the Negro community, where there are virtually no vacancies of any type.”54 An October 1948 editorial in the Sun described the “colored section of most cities” as “already dangerously overcrowded” and noted that only 2% of new housing built in Baltimore in 1948 was open to Black occupants, despite representing 20% of Baltimore’s total population.55 By 1950, Baltimore had 226,053 Black residents, representing 23.8% of the population but occupying only 19.4% of the city’s dwelling units. This pattern continued into the early 1950s—of the 53,000 permits issued for new homes in the Baltimore metropolitan area from 1950 to 1953, only 3,200 were open to Black households, even as the Black population increased another 10%.

In response to this housing crisis, beginning in the late 1940s, Black residents began to move into blocks at the western, northern, and southern edges of the segregated Black area known as Old West Baltimore (B-1373). In some cases, Black residents were met with violence by white neighbors. In 1945, a group of people, described by the Afro-American as “hoodlums who resented having the Millers move into a white neighborhood,” threw bricks at the home of James Miller and his family at 816 N. Fulton Avenue, breaking glass in the front door and windows.56 In August 1948, a house on the 1300 block of Payson Street just to the north of the district was subject to an arson attempt, attributed to retaliation against a white Jewish homeowner who had “broken” the block by selling a property to an African American homeowner in 1946.57 In July 1950, on the 2300 block of Lauretta Avenue, someone vandalized the home of Ms. Beatrice Sessoms, a native of North Carolina who came to Baltimore two years earlier, and her nephew.58

In reporting on the 1945 case of James Miller on Fulton Avenue, however, the Afro-American, suggests that violence was the exception rather than the rule, writing:

Of at least fifty houses on Fulton Avenue now owned by colored persons between the 500 and 1800 blocks, only one case of violence has been reported by one of the three families now known to occupy homes there. The James Miller family, which moved into 816 N. Fulton Avenue on February 15, reported that bricks were thrown through a window and door panel on the following Saturday. The second floor of this house is occupied by the William Montgomery family… Among Fulton Avenue property owners are the Rev. Hiram J. Smith, Dr. Bruce Alleyne and the Medicos Club, an organization of physicians and dentists. “For Sale” signs may be seen all along Fulton Avenue.59

These changes only accelerated following the US Supreme Court’s 1948 decision in the case of Shelley v. Kraemer. The landmark decision ended the legal enforcement of racial covenants (previously upheld by the Supreme Court in their 1926 decision in Corrigan v. Buckley) and marked a significant expansion in Black households’ access to new houses. In an interview for Dr. Edward Orser’s study on the racial transition of Edmondson Village, one Black west Baltimore resident recalled the almost alarming speed of his neighborhood’s racial transition in the late 1940s:

Black people started moving out of the confined areas somewhere around 1947 or 1948, but what would happen was that whites would evacuate a block or two blocks, and black people would move in. The evacuation would take place first. I remember streets like Fulton Avenue, Monroe Street—they were once totally white, and they went through the transition and changed somewhere between 1946 and 1949—that was the time I was in service. When I went in, there were no black people when I came out, there they were black streets… But it wasn’t integration… it was an evacuation.60

In 1949, Afro-American columnist Lula Jones Garrett quipped that Baltimoreans were playing the “change-the-address” game, explaining, “What with the local yokels forsaking the ghettos and moving into swankier mansions, it takes a special edition of the directory to locate your best friends these days.”61

The approval of the Housing Act of 1949 dramatically expanded access to mortgages for white Baltimoreans, but left Black activists feeling skeptical when federal officials expressed their concern over poor housing conditions for Black Americans. For example, Clarence Mitchell praised Albert Cole, administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency for a prominent speech before Detroit’s Economic Club on February 8, 1954, but noted that Cole’s “fine words” avoided “the basic problem.” Mitchell predicted “we shall continue to have the Levittown, Birmingham, and Baltimore type of problem” (meaning officially sanctioned residential segregation) until the federal government adopted a “flat policy” of non-discrimination.62

Historian Richard Rothstein, has argued that redlining by HOLC and the FHA in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s “necessitated the contract sale system for Black homeowners unable to obtain conventional mortgages” and “created the conditions for neighborhood deterioration” in historically segregated Black neighborhoods after World War II.63 Contract buying and the associated practice of “blockbusting” were reportedly widespread in Baltimore, Chicago, Cincinnati, Detroit, Washington, DC, and other cities.

In this exploitative practice, real estate speculators encouraged white fears of Black households moving into previously segregated white neighborhoods, to induce white property-owners to sell at reduced prices. The speculators could then re-sell the same houses to Black families at much higher prices. Because Black families had fewer options for financing, often the speculators would finance the purchase, charging much higher rates than white buyers could obtain under FHA financing. Rothstein emphasizes the connection between blockbusting and persistent housing segregation, writing:

Blockbusting could work only because the FHA made certain that African Americans had few alternative neighborhoods where they could purchase homes at fair market values.64

“Blockbusters” used a range of tactics to take advantage of both sellers and buyers. In an oral history, one white west Baltimore resident, Thomas Cripps, recalled seeing a suited man walking in the neighborhood around his home at 2323 Mosher Street carrying signs that read “This House is Not for Sale.” By implying that the neighborhood was imminently threatened with racial transition, the man likely hoped to motivate white homeowners to sell their house fast and at a low price. Two years later, Cripps’ family became the first household on the block to sell their home to a Black family—Ellsworth F. Davage, a Baltimore County schoolteacher, and his wife Elizabeth.65

For Black buyers like the Davages, blockbusters often offered to sell houses using land-installment contracts or buy-like-rent arrangements, also known as lease-option contracts, that allowed homeowners to purchase property without an initial down payment or closing charges. Since these arrangements did not immediately transfer title to the property, buyers risked losing their homes if they missed even a single payment. Consequently, while the homeownership rate for Black residents increased by 194% between 1940 and 1950 (compared to 58.8% for white residents), a 1955 survey by the Maryland Commission on Interracial Problems and Relations found that 53% of Black respondents had purchased their homes through contract buying arrangements rather than regular financing.66 During the late 1950s, the Maryland Commission on Interracial Problems and others finally engaged with the ongoing process of racial transition with the beginning of advocacy and organizing efforts to promote “neighborhood stabilization.”67

Baltimore Urban League, the Maryland Commission on Interracial Problems and Relations, and the Citizens Planning and Housing Association recruited community organizations to help combat continued white flight and avoid the rapid resegregation of newly integrated neighborhoods. In July 1958, the Allendale Lyndhurst Improvement Association’s president L. E. Larsen signed on to the plan but had little hope for success. Larsen observed that his area of west Baltimore was “already faced with pressure from blockbusting realtor tactics and population shifts” and grimly predicted that “the exodus from the city of the stable core of responsible citizens will likely be accelerated and the inevitable consequences will be a set-back to many of the long-range plans now being developed and implemented.”68

In 1959, local organizing around fair housing led to the founding of Baltimore Neighborhoods Inc. by James Rouse, Ellsworth Rosen, and Sidney Hollander Jr. The group sought to promote stable integrated neighborhoods by educating residents about fair housing laws, demanding enforcement, and pushing for stronger policies, but there were few neighborhoods where their efforts succeeded. The neighborhoods along Edmondson Avenue west of the Gwynns Falls were among many areas that flipped from segregated white to segregated Black in little more than a decade. The area south of Edmondson Avenue, now known as Allendale, changed from more than 99% white in 1950 to 62% Black in 1960 and, a decade later, 92% black. The Edmondson Village neighborhood remained 99% white in 1960 but had changed to 97% Black by 1970.69

Highway Building and Transportation Planning: 1930s–1960s

Highway construction was another major factor influencing regional housing. Income inequality limited automobile ownership among Black households and segregated Black neighborhoods were disproportionally displaced by highway projects. The pattern of road building in Black neighborhoods was well-established by the 1930s. For example, while the Howard Street Bridge over the Jones Falls was not completed until 1938, planners in the early 1920s were indifferent to the anticipated displacement of three blocks of Black households, explaining that the property they stand upon is “too valuable to be occupied by unsanitary, tumble-down residences.”70 In 1947, as the neighborhoods around Druid Hill Park began to change, the city started widening Druid Lake Drive.71 The plan to move more automobiles through the largely Black area included the conversion of Druid Hill Avenue and McCulloh Street into one-way streets prompted an unsuccessful 1948 lawsuit by the NAACP. In 1964, despite significant opposition from nearby residents, the city expanded Druid Lake Drive again.72

The most notable of the road projects planned and debated in this period was an east-west highway known as the Franklin–Mulberry Expressway. Planning for the project began in 1940 when City Planning Commission engineers first proposed a major east–west highway. In 1942, Baltimore commissioned a highway design from New York planner Robert Moses, who delivered a proposal requiring the demolition of 200 city blocks and the displacement of 1,900 residents. Moses was unconcerned with the possible displacement of residents along the highway corridor, suggesting, “Nothing which we propose to remove will constitute any loss to Baltimore.”73 Moses argued that the demolition of “slums” was a benefit as “the more of them that are wiped out the healthier Baltimore will be in the long run.”74

The passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which authorized the interstate highway system and expanded funding for road projects (including the proposed east-west expressway). By the 1960s, concern over the highway plans developed into organized opposition. For example, in 1966, a group of west Baltimore residents established the Relocation Action Movement (RAM) to fight for fair compensation for west Baltimore residents displaced by the highway. RAM members clearly saw the connection between the highway proposal and the broader conditions of racial segregation and inequality. When transportation planners rejected the group’s proposal to direct the highway into a tunnel on the basis of the substantial costs, one RAM member exclaimed, “It always has been expensive to operate a segregated society.” RAM joined a large coalition of community organizations known as the Movement Against Destruction (MAD) that undertook a prolonged campaign of protest and legal action to fight the construction of the highway.75 While the system was never fully completed, a section of the highway was cut through west Baltimore in the mid to late-1970s destroying hundreds of houses in the path.

Postwar Urban Renewal: 1950s–1960s

Local “slum clearance” campaigns dating back to the late nineteenth century expanded in the 1930s through Public Works Administration support for “slum clearance.” In the 1940s, Baltimore gained acclaim for a new code-based housing strategy known as the Baltimore Plan, that, as historian Emily Lieb observes, “sought to use housing-code enforcement and privately-sponsored restoration efforts as a substitute for public housing.”76 In 1945, the Commission on City Plan of Baltimore published a report, known as the “Hubbard Report,” that highlighted five “blighted residential areas” of the city for redevelopment, all largely occupied by Black households. The report led to a ballot amendment approved by Baltimore voters to establish the Baltimore Redevelopment Commission and empower the commission with the eminent domain authority they would use to acquire private property for redevelopment.

One of the largest areas targeted for redevelopment was the area around the Fifth Regiment Armory, which had been labeled “Redevelopment Area 12” in the 1940s, considered as the “Amory site” for the convention center in the early 1950s, and eventually designated as the Mount Royal Fremont urban renewal area by the Baltimore Urban Renewal and Housing Authority (BURHA). In September 1953, Dr. Robert L. Jackson, the only Black member of the City Planning Commission, criticized a proposal to locate a new state office complex in the area, noting that the project would force 950 Black families to move. Richard L. Steiner, director of the city’s redevelopment projects, did not offer much hope that residents could return to rent in the area following the construction of planned buildings. While he anticipated new housing for 370 families, he refused to guarantee that the new buildings would be open to Black tenants, saying, “That’s in the hands of the redeveloper.”77

On November 4, W. A. C. Hughes Jr., a Black attorney who frequently represented the local NAACP in civil rights cases, joined a meeting of the Property Owners and Merchants Association of the Third Redevelopment Area Project No. 12 at Union Baptist Church on Druid Hill Avenue and encouraged neighbors to organize and fight. Hughes argued that “under no matter, shape or form” could most of the project area “be justifiably described as slum or blighted areas under the definition outlined in the codes of the city and State.”78 At a City Council committee hearing on November 14, Hughes testified that the proposed demolition sites included his own office and property owned by his mother and warned that redevelopment turned Black Baltimoreans into “the displaced person.” He cited a survey from the Baltimore Urban League of the recent redevelopment of Waverly which found that the city paid Black families an average of $3,726 for their homes but paid $4,108 to white families—at a time when it cost Black families an average of $7,836 to purchase a home and only $6,126 for white families.79 The mayor, City Council, and white members of Mount Royal Protective Association pushed on despite objections, and plans for the area’s redevelopment moved forward.

The city’s plans for the area received a boost in 1955 with an amendment to the Housing Act that permitted local governments to use the program to fund the construction of public facilities. The first Housing Act in 1949 set aside $1 billion in federal aid for postwar urban renewal, demolition, and redevelopment in “slum” areas. The subsequent Housing Act of 1954 added new requirements for comprehensive planning but reduced requirements for building new affordable housing in the areas targeted for clearance. Later amendments exempted universities from earlier provisions requiring that projects include new housing construction.

Baltimore’s elected officials and most housing reformers embraced the new infusion of federal funding. In 1956, Mayor Theodore McKeldin merged the Baltimore Redevelopment Commission, with the Department of Health’s Office of Housing and Law Enforcement, and parts of the Department of Planning to create the new Baltimore Urban Renewal and Housing Authority (BURHA). BURHA took over the designation of a growing number of urban renewal areas in and around downtown Baltimore and the administration of related projects.

Urban renewal encountered critics from the very beginning—although few white observers remarked on policy’s discriminatory effects. In 1955, a Sun editorial reflected on the proposed demolition around Harlem Park (an area the Commission on City Plan of Baltimore and the Redevelopment Commission called "ripe for urban renewal"), noting:

Even today the park is still there and the houses which surround it are for the most part gracious and dignified in their outward appearance... Inside they may be ghastly tenements, for all we know. But is it really necessary to dispose of them as so much rubbish?80

By May 1957, Elizabeth Murphy Philips could report on a host of businesses, churches, and community groups displaced from urban renewal areas in east and west Baltimore. After 17 years at 1107 Madison Avenue, C. A. Johnson's Barber Shop had moved to 2026 Smallwood Street. After nine years at 1017 Madison Avenue, Charlie and Myrtle Burn's Club 1017 was planning a move to a “newly-refurnished” building at 1426 Pennsylvania Avenue. Displaced churches included Trinity A.M.E Church (moving from Biddle and Linden Streets to Hoffman and Collington) and Perkins Square Baptist (moving from George and Ogston Streets to Warwick and Edmondson). After 15 years in operation at 406 Dolphin Street, Day's Employment Agency decided to open a second location at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Presstman Street—"just in case" their block of Dolphin Street was selected for demolition. Other businesses were threatened with demolition, but had not yet found a new building, including the York Hotel at Dolphin Street and Madison Avenue and the W. Sampson Brooks Elks Lodge at 1202 Madison Avenue.81

In many of the city’s urban renewal areas, a disproportionate share of the displaced residents were black. According to federal reports, between 1955 and 1964, 1,614 families (58% identified as black) were displaced from the Mount Royal Fremont urban renewal area between Bolton Hill and Mount Vernon. The extension of the Mount Royal Fremont urban renewal area along Eutaw Street resulted in the displacement of another 1,518 families (57% identified as black). The Mount Royal Plaza Project (the current location of the State Center office complex) resulted in the displacement of 1,328 families (84% identified as black). In east Baltimore's Broadway area, 95% of the 1,110 families, and, in Harlem Park's two designated urban renewal areas, 100% of the 733 displaced families are identified as black.82 While urban renewal projects resulted in the construction of new schools, senior housing, and public office buildings, the consequent displacement was traumatic for many residents and did not address the structural inequality that continued to drive disinvestment in historically segregated Black neighborhoods.

Schools and Education

In the 1930s, Black families in Baltimore and the surrounding region grew increasingly impatient with the discriminatory under-funding of segregated Black schools. For years, the parents in Baltimore County had sought the construction of a high school for their children. The county refused their requests and continued the practice of sending Black students to segregated high schools in city. The state of Maryland even paid tuition for Black students to attend colleges in other states if they sought a college degree unavailable at one of Maryland’s historically Black institutions. These examples illustrate the challenges around school equality as parents, students, and activists sought to secure equal opportunities and equal facilities even within the segregated system.

Ultimately, however, demands for equality turned into demands for integration. The successful case of Murray v. Pearson (1935) led to the integration of the University of Maryland School of Law. Legal action by the NAACP also forced the early desegregation of Baltimore Polytechnic High School in 1952. Following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, the pace of change increased. Baltimore officially ended the long-standing practice of maintaining segregated school systems. Unfortunately, by the early 1960s, it was clear that most students in the Baltimore region, both Black and white, were still attending segregated schools. Parent-led efforts for more substantial change were undermined by the persistence of housing segregation across the region and white elected officials who refused to make school desegregation a political priority.

School Equality and Desegregation Before Brown: 1930s–1950s

During the 1930s, school administrator Francis Wood continued to build on the changes suggested by the 1922 Strayer school survey. Between 1929 and 1940, Wood increased attendance rates to more than 85% for Black elementary and junior high school students and more than 90% for Black high school students.83 In 1931, the old State Normal School was converted into the George Washington Carver Vocational-Technical High School, the first public school in Maryland to provide vocational training to Black high school students. The building, located at the northeast corner of N. Carrollton and W. Lafayette Avenues, was originally designed in 1876 by Francis Earlougher Davis, and vacated in 1915 when the segregated white Normal School moved to Towson. The building was later converted to school district offices before becoming a high school.

While teacher salaries had been effectively equalized for white and Black teachers in Baltimore City in 1925, other jurisdictions around the state continued to discriminate against Black educators. Between 1936 and 1939, Black teachers, represented by the Maryland State Colored Teachers Association, the Baltimore branch of the NAACP, and the NAACP national office, led a statewide campaign to address this issue. The campaign forced the Maryland State School Survey Commission to consider the issue, and new legislation established an “equalization fund” designed to subsidize equal salaries for white and Black teachers statewide by January 1942 and for white and Black school supervisors by 1945.84 According to historian Andor Skotnes, the successful statewide advocacy campaign was “an important factor in the resurgence of the freedom movement in the ‘border’ and southern states of the late 1930s and early 1940s” seeking to follow Maryland’s example. It was also a vindication of attorney Charles Hamilton Houston’s “strategic vision” of using Maryland as a “legal laboratory” where civil rights advocates could combine “litigation based on the Fourteenth Amendment with mass mobilization to overturn Jim Crow in the educational sphere.”85

Even as Francis Wood, along with many Black teachers and families, advocated for improvements to Black schools within the segregated system, others fought to end school segregation everywhere from elementary schools to universities. The best-known case from this period was Murray v. Pearson (1935), where Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston won Donald Gaines Murray’s admission to the University of Maryland law school. The court determined that by providing only one law school for Maryland students the state could only fulfill their obligations under the Equal Protection Clause of Fourteenth Amendment by opening the school to all students—both white and black. The case was the first major suit in the NAACP’s broader education campaign, and attorney Charles Hamilton Houston cited the extensive coverage of the Murray case in the Afro-American as a model of how “court proceedings” can help sway public opinion.86

National NAACP staff and more than 500 delegates from across the country celebrated the local win at the NAACP’s annual meeting in Baltimore later that year. Juanita Jackson had recruited around 200 youth delegates for the event and, according to Patricia Sullivan, the gathering “offered a venue for delegates to report on developments in their communities to a nationally representative group; develop contacts; debate, refine, and develop strategies and tactics; and see their efforts within the full context of NAACP activity.”87 In a speech to the delegates, Walter Francis White presented the victory in Murray as a promising sign: “If you are willing to struggle with us… who knows but there may be Negroes in the universities of states such as Mississippi and Arkansas.”88

The following year, the NAACP offered Thurgood Marshall a six-month position at their New York office. In October 1936, Marshall closed his office in Baltimore and moved to New York to start full-time.89 Fortunately, Marshall and the NAACP continued to support educational advocacy in Maryland. For example, the NAACP’s National Legal Committee campaign against segregated schools and discriminatory education policies led the Maryland General Assembly to pass a law mandating equal school terms for white and Black students in 1937.90

Persistent advocacy finally won Black Baltimoreans a seat on the city school board. On April 9, 1942, Dr. Carl Murphy, acting as chairman of the Baltimore Citizens Committee for Justice, sent a letter to Mayor Howard Jackson arguing for the appointment of an African American person to the school board.91 Where prior efforts had failed, this one succeeded with the 1944 appointment of George F. W. McMechen, an 1895 graduate from Morgan College and an African American lawyer, to the Baltimore City Board of School Commissioners.92 In the late 1940s, Carl Murphy and Juanita Jackson Mitchell began pushing to desegregate Baltimore public schools, and, in 1952, the NAACP and Thurgood Marshall successfully forced the city to permit a small group of African American students to enroll at the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute on a limited basis.93

In the years following the early success at the University of Maryland law school, barriers to Black students and faculty began to fall at other area colleges, universities, and professional schools in Baltimore and Maryland. In 1947, Dr. Ralph J. Young became the first African American to join the teaching staff at Johns Hopkins Hospital. In 1950, Frederick I. Scott became the first African American student to graduate from Johns Hopkins University. That same year, Juanita Jackson Mitchell became the first African American woman to graduate from the University of Maryland law school. In 1951, Hiram Whittle became the first Black undergraduate to enroll at the University of Maryland in College Park.94

School Integration After Brown: 1954–1960s

In contrast to the “massive resistance” seen in other Southern cities, Baltimore responded quickly to the 1954 US Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The school board announced a new “open enrollment” policy where Black and white students could attend any school. After a brief outbreak of unrest at four recently integrated white public schools, representatives of nineteen civic, religious, educational and labor groups came together to form the Coordinating Council for Civic Unity to support the “peaceful opening of schools.” The group, composed largely of white organizations, reportedly “served as an information clearing house and ‘fire brigade’ on the alert for other racial friction.”95 Baltimore’s move won praise at the time, but historian Howard Baum notes the critical flaw in the plan: “Explicitly, [the school board] would not discriminate against black children; implicitly, neither would it act on their behalf.”96

Within a few years, two trends in student enrollment were clear. The first was the growing but still moderate racial integration of city schools. The second was the school district’s transition from majority white to majority Black as large numbers of white families withdrew their children.97 Baum has argued that the ambiguity of the “open enrollment” policy may have “added to racial anxiety” for white families: “Parents could not know what a school’s makeup would be when classes started…. This uncertainty not only added to anxiety but also made leaving city public schools a choice with a more predictable outcome."98 By 1960, a majority of students in Baltimore’s school district were black. While one-third of Black students now attended formerly white schools, many students continued to attend segregated schools.

In 1963, a group of frustrated white and Black parents, known as “28 Parents,” presented a report to the school board describing how students continued to experience segregation. The activists identified three contributing factors:

-

Building new schools in racially segregated neighborhoods made a segregated student population more likely

-

Prioritizing enrollment for neighborhood children when schools were “overcrowded,” reinforced existing patterns of segregation

-

Administrators acting directly and indirectly to discourage integration

Regarding these administrative actions, historian Howard Baum described how some white principals “encouraged white parents to transfer their children out when black enrollment grew” and rejected any Black students who applied to transfer to predominantly white schools.99 Even within integrated schools, “ability tracking” separated Black and white students within shared school buildings. The 28 Parents report highlighted a disturbing reality for civil rights activists as Baum concluded:

After a decade of legal segregation, most children attended class with majorities of their own race… By the time the board ended practices that limited choices, the desegregation policy had a ten-year history associated in the public mind with continuing segregation."100

When, the 1964 Civil Rights Act created a federal interest in desegregating schools, the federal government began to put pressure on city officials to take further action. Still, progress remained limited. In August 1967, one report observed that while the Baltimore City and Baltimore County school systems had “made some progress toward desegregation within their systems,” but, when “considered as a single ‘metropolitan’ system,” they had made “no progress at all, by any criterion.”101

Public Accommodations

Equal access to public accommodations continued to be a highly contested issue during this period. Baltimore’s growing Black population demanded more than the limited number of parks and recreational facilities open to Black residents. In addition, during and after World War II, rising expectations of equal rights for Black Americans as consumers helped make theaters, department stores and restaurants into popular targets for protest. Student groups, particularly those from Morgan State College, proved instrumental in efforts to desegregate downtown department stores and lunch counters. By the early 1960s, public pressure, lawsuits and legislation had resulted in the desegregation of public beaches and parks, as well as department stores and theaters. The changes spread across the state after Maryland passed a law to desegregate public accommodations in 1963.

Public Parks and Recreational Facilities: 1930s–1950s

The 1930s and 1940s saw several notable campaigns to challenge segregation in Baltimore’s public parks and recreational facilities.102 For example, in September 1934, after persistent requests by Black golfers the Carroll Park (B-4609) golf course began allowing them to use the course but kept them segregated from white golfers by limiting them to specific days of the week. In 1938, two Black golfers, Dallas Nicholas and William I. Gosnell, sued Baltimore City to try to overturn this policy but they were unsuccessful.103

After World War II, a number of youth-led protests were more successful. On December 17, 1947, a group of white and Black young people organized an integrated youth basketball game at Garrison Junior High School to protest segregation in local youth recreation. Another interracial protest took place on July 11, 1948 when a group of young Black and white tennis players organized a game on the tennis courts at Druid Hill Park (B-56). The protest led to a lawsuit against the city, Boyer v. Garrett (1949), that resulted in the court overturning the city’s long-standing policy of racial segregation in city parks.104

In 1950, a group of Black activists attempted to purchase tickets for the beach at Fort Smallwood Park (AA-898), a popular recreational park owned and managed by Baltimore City but located in Anne Arundel County. When park workers refused to sell tickets to the activists, they sued the city initiating a prolonged legal action. Eventually, in 1955, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals found in favor of the activists in Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City v. Dawson, linking the Brown decision to the necessity of integrating public facilities, writing:

It is obvious that racial segregation in recreational activities can no longer be sustained as a proper exercise of the police power of the State; for if that power cannot be invoked to sustain racial segregation in the schools, where attendance is compulsory…it cannot be sustained with respect to public beach and bathhouse facilities, the use of which is entirely optional.105

In November 1955, the US Supreme Court ended the debate by upholding the decision by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals without even issuing a separate opinion.106

The critical importance of equal access to parks and recreational facilities was tragically demonstrated in 1953 when a Black boy died while swimming with friends in the Patapsco River. The only swimming pool open to Black residents was Pool No. 2 located in Druid Hill Park. Arguing the boy would not have died if the public pool in his southwest Baltimore allowed Black swimmers, the Baltimore NAACP filed suit against the city to force the desegregation of Baltimore’s public swimming pools. The NAACP won their case and the city’s newly desegregated pools opened on June 23, 1956.107

Theaters, Department Stores and Restaurants: 1938–1960s

In many American cities, including Baltimore, downtown department stores had special significance. Historian Paul Kramer called the stores “some of Baltimore’s most prominent sites of civic culture and modernity.”108 The combination of prominence and prejudice made these stores a key target for protests over an extended period from the late 1930s through the 1960s. The discrimination African Americans faced in public accommodations was not just one of simple exclusion. Historian Paul A. Kramer notes that the discriminatory “racial practices” at Baltimore’s downtown department stores included three main aspects:

-

Refusing to serve Black customers at lunch counters

-

Prohibiting Black customers from trying on or returning clothing, and

-

Discriminating against Black workers by only hiring Black people as maintenance or stockroom workers, elevator operators, porters, and restroom attendants.

The prohibition on returns from Black customers (known as the “final sale” policy) reveals one of the fundamental motivations behind racial segregation—“anxieties and fears about physical contact between whites and blacks.” Kramer continues to explain:

For most whites, blacks represented sources of unspecified physical and moral pollution … Black and white bodies might “touch” in the exchange of forks and plates at store lunch-counters. Even more threatening to whites was the possibility that the clothes they tried on or purchased might bear an invisible taint of black physical contact.109

Notably, in early 1943, when the Baltimore NAACP sought to overturn the state’s Jim Crow laws, the repeal bill they supported was sent to state legislature Hygiene Committee rather than the Judiciary Committee for consideration.110

Some of the earliest efforts to change store policies started between 1938 and 1940 when the Baltimore Urban League and NAACP met for private negotiations with downtown department store owners and urged them to end their discriminatory policies against Black shoppers. Local Black activists met again with a representative of the Retail Merchants Association in February 1943, but no policy changes followed. A more public protest started in 1945 when the Afro-American newspaper began their “Orchids and Onions” campaign to celebrate stores that did not discriminate against Black shoppers (“Orchids”) and to shame downtown department stores with discriminatory policies (“Onions”).111

One early challenge to these segregationist policies came from an interracial group of activists affiliated with the local chapter of CORE who used public pressure and sit-ins to protest segregated lunch counters—a strategy used previously in New York City in 1939 and by CORE members in Chicago in 1942. Afro-American columnist Mrs. Elizabeth Murphy Phillips noted their success on November 7, 1953:

Thanks to the Committee on Racial Equality, (CORE), the Urban league, and the Americans for Democratic Action, (ADA), more stores in the 200 block W. Lexington St. are realizing there is no color line in the dollars you spend. Lunch counters and restaurants in the Kresge and Woolworth Five and Ten have been serving all customers for several weeks. McCrory’s has just reversed its policy and will serve all comers […] Schulte United in the 200 block Lexington is still acting silly.112

The scope of such campaigns was limited in comparison to the overall challenge for Black residents in the 1950s. For example, one 1955 survey found that 91% of 191 randomly selected Baltimore businesses reported either the “exclusion” or “segregation” of Black customers.113 In January 1955, CORE’s campaign against segregated lunch counters on Lexington Street ended with the successful desegregation of the Read’s Drug Store chain.