Black residents and activists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century sought to fulfill the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment through organizing, protest, and legal action. Clear examples of this work are found in two of the most significant civil rights organizations in Baltimore’s history: the Brotherhood of Liberty, established in 1885, and the Baltimore branch of the NAACP, established in 1914.

The promise of equality and political power, however, encountered stubborn and violent resistance as white Americans promoted the ideology and politics of white supremacy following the end of slavery. White Americans embraced Jim Crow segregation across the country and the Democratic Party pursued an aggressive strategy of disenfranchising Black voters in the southern United States. This national and local commitment to racial segregation came at a critical moment in Baltimore’s physical development and growth. In 1888, the city annexed a ring of developing suburbs from Baltimore County and, in the early 1890s, private investors built new electric streetcar lines to serve the residential neighborhoods extending out from the city center. Expanding transportation options supported the early growth of rowhouse neighborhoods for white Baltimoreans. Black residents, however, were excluded from these areas by threats of white violence, the refusal of property owners to sell or rent to Black residents, and, later, restrictive covenants excluding all non-white residents.

The push and pull of Black activism and white reaction were central to the electoral politics of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century Baltimore, including a statewide push for the disenfranchisement of Black voters in the early 1900s and national debates over women’s suffrage in the 1910s. Segregation shaped how Baltimore’s Black households occupied homes, organized civic groups, and used public space. Widespread discrimination largely determined the experiences of Black workers seeking jobs and Black students and teachers dealing with unequal schools and salaries. The Brotherhood of Liberty and the NAACP both tackled this wide range of issues criticizing injustice everywhere from steamships to schools to prisons and police stations.

Early Activism and the Brotherhood of Liberty: 1880s–1900s

On June 22, 1885, Rev. Harvey Johnson invited five Baptist ministers to his home at 775 W. Lexington Street. The group hoped to turn the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted equal protection under the law, into a better life for their Black congregants, families, and neighbors. To achieve this goal, they established the Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty and declared their mission “to use all legal means within our power to procure and maintain our rights as citizens of this our common country.”1

Harvey Johnson was born to enslaved parents in Fauquier County, Virginia, in 1843 and arrived in Baltimore after the Civil War in 1872 to serve as pastor at Union Baptist Church (B-2965). Four years earlier, the church had moved from Lewis Street (near Orleans Street and Central Avenue) in east Baltimore to the former Disciples Meeting House on North Street (today known as Guilford Avenue) between Saratoga and Lexington Streets.2 In 1877, writer Amelia Etta Hall moved to Baltimore from Montreal, Canada, where she met and married Harvey Johnson. Through the couple’s leadership, membership in the church increased from 268 people in 1872 to over 2,000 in 1885—a powerful base of support for the Brotherhood’s activist agenda.3 By October 1885, the Brotherhood of Liberty had won its fight to see then 26-year-old Everett J. Waring admitted to the state bar, making Waring the first Black lawyer able to practice in Maryland. In her study of the Brotherhood, historian Bettye Collier-Thomas quotes Johnson’s understanding of the importance of Black lawyers to the broader agenda of Black freedom: “there must be Negro lawyers, men who have themselves suffered and who will fight the people’s fight, because the people’s fight will be their own battles!”4

Over the next few years, Johnson, together with Waring and other allies, waged an energetic campaign against the state’s prohibition on interracial marriage and discriminatory provisions in the state bastardy law. The bastardy law entitled unmarried white women to seek financial support from a child’s father but did not offer the same right to unmarried Black women. These discriminatory state policies, known to activists as the “black laws,” had their roots in the restrictions imposed on both enslaved and free Black residents before the Civil War.5 The Brotherhood of Liberty began planning to bring a test case that would take the issue to the state Supreme Court, and a group of women connected to the A.M.E church started raising money to cover the cost of a lawyer.

Finally, in early 1888, the Maryland state legislature, facing legal threats and determined public pressure, enacted an indirect solution. The legislature updated the code of general public laws and dropped the word “white” from state bastardy laws as well as with the stated requirements for jury service and admission to the bar.6 The campaign’s success was both symbolic—an official recognition that the state’s laws should not discriminate—and practical—clearing the way for Black Baltimoreans to use state courts in their legal fight for equal treatment under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments.

Historian Dennis Halpin explains the Brotherhood of Liberty’s activism “sought to further define the implications of the Fourteenth Amendment, draw the wider community into activism, and seek redress for various injustices.” The group’s strategy of using legal test cases became a model for successful legal activism in the twentieth century—an approach most famously championed by Charles Hamilton Houston, dean of Howard University Law School and the NAACP’s first special counsel.7

On September 6, 1888, the Brotherhood of Liberty celebrated the community’s victory by hosting a picnic at Irving Park near Annapolis Junction, inviting Black Marylanders and friends from Washington, DC, to gather together, recognize their progress, and rally for the work ahead. “We ask not special legislation, but the enforcement of the law as it is,” Rev. Johnson declared before a crowd of 2,000 people. Johnson urged continued pressure:

We must organize, raise money, contest our legal wrongs in the courts. We should agitate and contend until every vestige of color discrimination is swept from the laws. We demand educational facilities for our colored children; we demand colored teachers for colored schools; we demand the right to travel upon common carriers; we demand non-molestation by bad white men; we demand the same law meted out to other men. This is our case; it is just. The right will triumph.8

This initial court victory enabled further legal action by the Brotherhood. In addition to its work to amend the state Bastardy Act and challenge laws prohibiting intermarriage, the Brotherhood of Liberty also pushed for improved educational conditions for Black students and represented the rights of Black workers charged with murder during the Navassa Island trial in 1889 and 1890. In 1889, the workers rose up in protest over brutal conditions in a remote guano mining operation owned by the Navassa Phosphate Company of Baltimore, leading to the death of five white supervisors. Historian Bruce Thompson argued that these cases were distinct from earlier advocacy efforts by suggesting that the Brotherhood of Liberty in the 1880s and 1890s used the law to “defend black civil rights against encroachments by whites.” Thompson also highlighted the limits of their advocacy, noting that the Brotherhood was never in a position to use legal suits to “strengthen, re-establish, or expand black civil rights.”9

The Brotherhood of Liberty and other activists faced an enormous challenge—an explicit and pervasive culture of white supremacy that dominated American society and politics in the 1880s and 1890s. White Democrats throughout the South, Maryland included, responded to the rising power of residents since Reconstruction by seeking to disenfranchise voters and create a culture of segregation. “Whites created the culture of segregation in large part to counter black success, to make a myth of racial difference, to stop the rising,” observed historian Grace Elizabeth Hale.10 It was no surprise then that the Maryland legislature rushed to pass a ban on interracial marriage in January 1884—just weeks after Maryland-born Frederick Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white suffragist and abolitionist.11 White Baltimoreans—including Confederate veterans, Ladies’ Memorial Associations, elected officials, and the Democratic Party—deployed racist stereotypes and “Lost Cause” myths to justify lynchings, disenfranchisement, discriminatory employment practices, unequal schools, and unjust courts and policing in the late nineteenth century.12 For example, in 1891, Baltimore lawyer William Cabell Bruce wrote a short book, entitled The Negro Problem, that made a case for disenfranchisement with Social Darwinist arguments using the language of science to justify a belief in inferiority and white superiority.13

The movement did not go unchallenged. Bruce’s book prompted a response from Rev. Harvey Johnson whose published remarks for the Monumental Literary and Scientific Association of Baltimore attacked the logical and historical basis of Bruce’s arguments. But, by January 1894, speaking before a crowd at Metropolitan A.M.E. Church in Washington, DC, Frederick Douglass despaired: “I hope and trust all will come out right in the end but the immediate future looks dark and troubled. I cannot shut my eyes to the ugly facts before me.”14 Little more than two years later, the US Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) granted federal approval to racial segregation and encouraged the spread of Jim Crow policies across the country by establishing the “separate but equal” doctrine and legitimizing state laws that permitted racial segregation.

The move to erect public Confederate monuments in Baltimore illustrates how these ideas grew to dominate popular culture around the end of the nineteenth century. Although the Society of the Army and Navy of the Confederate States in Maryland resolved to erect a monument on Eutaw Place back in January 1880, Mayor Ferdinand Latrobe, rejected the idea as too divisive.15 Twenty-three years later, on May 2, 1903, hundreds of people, including mayor and Confederate veteran Thomas Hayes, gathered at the dedication of the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument on Mount Royal Avenue. The crowd waved “the battle flag of the old days,” listened to Maryland, My Maryland (a song written by James Ryder Randall, a Maryland native and Confederate sympathizer, with lyrics calling on Maryland to join the Confederate rebellion against the federal government), and celebrated the aging white Marylanders who joined the Southern rebellion 40 years earlier.16

The new monument directly followed the Democratic Party’s return to local political power through an explicitly white supremacist campaign. While the Democratic Party largely dominated city and state politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, in 1895, Republican Mayor Alcaeus Hooper and Governor Lloyd Lowndes Jr. won office in an “landslide” election that gave Baltimore a Republican Mayor and Governor for the first time since 1867. Republican candidates for City Council overtook Democratic candidates in an overwhelming 17 of the city’s 22 wards.17

Regrettably for the 50,000 Marylanders who helped vote Republicans into office, according to historian Bettye Collier-Thomas, “once elevated, the Republicans all but ignored black interests.” In response to their 1895 loss, local Democrats rallied around slogans labelling Baltimore a “White Man’s City” and elected Thomas G. Hayes as mayor in 1899.18 Segregationists who won electoral victories based on the suppression of voters across the country were emboldened by the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision to enact new Jim Crow laws. For example, in 1904, Maryland passed a measure mandating racially segregated railroad coaches and, in 1908, extended the law to include electric trolley lines and steamboats.19 Historian Bruce Thompson noted that opponents to the law in Baltimore secured “an exemption [from the law] for travel within Baltimore” but, outside the city, all Marylanders “suffered the ignominy of being separated.”20 While the 1899 election ultimately resulted in the school board hiring more teachers for segregated schools, it served a segregationist political agenda—ensuring no white teachers would encounter students.

In the face of these new challenges, residents organized to fight back wherever they could. Baltimore’s churches, newspapers, political clubs, and civic organizations spoke out against the onslaught of attacks on their equal rights. The 31 newspapers established in Baltimore between 1856 and 1900 helped to spread residents’ shared concerns through editorials and reporting on injustice in Baltimore and around the country. One of those papers holds a unique place in the development of the civil rights movement: the Afro-American newspaper. John H. Murphy Sr., a 51-year-old veteran of the US Colored Troops, established the Afro-American newspaper in 1892 after combining his own church newsletter, The Sunday School Helper, with two other publications: The Ledger, established in 1882 by Rev. George Freeman Bragg, rector of St. James Episcopal Church, and The Afro-American, published by Rev. William M. Alexander, pastor at Sharon Baptist Church and a founding member of the Brotherhood of Liberty. Over the next several decades, the Afro-American newspaper (later known simply as the AFRO) grew into national newspaper with editions in 13 major cities. Ultimately, together with thousands of Black people in Maryland and Baltimore, Rev. Harvey Johnson’s Brotherhood of Liberty, and the community the group represented successfully frustrated “white attempts at disfranchisement and segregation” and laid the foundation for the generation of activists that followed in the early twentieth century.21

The Baltimore NAACP and Continued Resistance: 1900s–1920s

The Brotherhood of Liberty evidently faded from existence by the early twentieth century. When local activists organized the Maryland Suffrage League in 1905, then 62-year-old Johnson declined a nomination as the group’s president saying that a “younger man should lead race battles.” Johnson’s efforts were far from forgotten, however. In 1917, as a group of Black lawyers recognized the 25th anniversary of the 1885 legal victory over their right to practice law in Maryland by presenting Johnson with the gift of “a handsome silk umbrella.”22 These same lawyers, including W. Ashbie Hawkins, Warner T. McGuinn and George W. F. McMechen, joined legal campaigns and defense committees rallying opposition to lynching and disenfranchisement in the 1900s and housing segregation in the early to mid-1910s. Many Black Baltimoreans saw the clear continuity between oppression under slavery before the Civil War and current threats to Black freedom. For example, in October 1913, Warner T. McGuinn, a local Black attorney then residing at 1911 Division Street, observed: “Physical slavery has been abolished, but its subtler forms are still here. Disfranchisement, ‘jim crowism’ and segregation are but the subtler forms of race slavery.”23

Across the country, individuals engaged in anti-racist activism, mutual support, and interracial organizing began to shape new national movements but remained divided on the best way to achieve greater security, health, and prosperity for Black Americans. Booker T. Washington was a national leader from Alabama whose work exemplified an “accommodationist” approach. Washington encouraged the uplift of Black citizens through education and entrepreneurship over direct challenges to discriminatory laws in hopes of avoiding a white backlash to his activities—an approach most famously captured in his 1895 speech known as the Atlanta compromise.

By the turn of the twentieth century, there was growing frustration with this approach among many Black Americans. Harvard-trained sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois offered a sharp critique of Washington’s accommodationist approach in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folks. Du Bois pointed to Booker T. Washington’s 1895 Atlanta compromise speech as an example of "the old attitude of adjustment and submission." Du Bois predicted that if Black Americans followed Washington’s recommendation to focus on “industrial education, the accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South,” it would ultimately lead to disenfranchisement, “a distinct status of civil inferiority” for Black Americans, and the withdrawal of support for Black Americans seeking higher education. Instead, Du Bois sought to change public opinion and force white Americans to recognize that political and civic equality was essential for both the well-being of Black Americans and the health of American democracy.24

In July 1905, Du Bois joined William Monroe Trotter and a number of others who opposed an accommodationist approach and formed a new civil rights organization known as the Niagara Movement. The participants at the group’s first annual meeting at the Erie Beach Hotel in Ontario, Canada, included Rev. Garnett Russell Waller. Waller lived at 325 E. 23rd Street (near Trinity Baptist Church at Charles and 20th Streets) and served as the Niagara Movement’s Maryland secretary.25 The next year, the organization met in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, where Rev. Harvey Johnson gave the opening invocation at the group’s members-only business meeting.26

Two years later, in August 1908, the Springfield, Illinois, race riot resulted in three days of mass violence where 5,000 white Americans attacked their Black neighbors. At least 16 people died, and white rioters destroyed dozens of homes and businesses. The shock of the violent attack inspired three white New Yorkers to organize a national conference including both white and Black activists, W. E. B. Du Bois among them, to meet in New York City on February 12, 1909—the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth—and form the National Negro Committee. At the group’s second meeting on May 12, 1910, the participants established a more permanent organization—the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1912, Black Baltimoreans established the first local chapter of the NAACP, but initially struggled with uncertain leadership and limited financial support.27 President Woodrow Wilson’s move, shortly after taking office in March 1913, to re-segregate the federal workforce and facilities in Washington, DC, led the Baltimore branch to join activists in Boston, Detroit, Topeka, Denver, Tacoma, Seattle and Oakland in holding mass protests and writing letters to the President protesting what the NAACP called Wilson’s “officializing race prejudice.”28

A growing willingness among Black Baltimoreans to organize and act against racism is clear even before the local chapter of the NAACP was established. For example, when two advance agents for the notoriously racist play The Clansman arrived in Baltimore in March 1906, Black waiters at the St. James Hotel at the southwest corner of Charles and Centre Streets refused the agents service in protest, reportedly with the encouragement of the “Constitutional League.”29 The Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith’s movie based on The Clansman, screened for the first time in Baltimore the evening of March 6, 1916, before a crowd at Ford’s Theatre that “packed the house to its utmost limit.” The 1871 theater on Fayette Street near Eutaw Street hosted the show for seven weeks while “beating all records for length of run and for receipts.”30 The screening drew outrage from the writers at the Afro-American newspaper who had been closely following the NAACP’s national campaign to restrict the film’s distribution. Two days after the opening night at Ford’s, the newspaper reported that “yells of rage and screams of hate” elicited by the film “did not cease with the end of the show.” The paper quoted two contrasting responses to the film: a “colored man” who called it “the most disgusting thing I have ever seen,” and a white man who said, “I should like to kill all of the damn niggers in the United States.”31

The Birth of a Nation’s commercial success reflects the significant difficulties the NAACP faced locally and nationally. Organizers also often struggled to raise and sustain financial support for the movement. In June 1920, activist Addie Hunton came to Baltimore as a field organizer and recruited a large number of new members for the local chapter. When she returned to Baltimore in January 1923 for a mass meeting together with A.M.E. Bishop John Hurst, she wondered at the chapter’s failure to sustain their membership, writing: “Where did 2,000 members signed up in 1920 go? … People are interested everywhere. We fall down on the field for want of a sustained leadership.”32 The local anti-lynching movement faltered by the late 1920s, as the campaign by the national NAACP could not push federal anti-lynching legislation past intransigent opposition in the US Congress. Similarly, despite their eventual success in overturning Baltimore’s segregation laws, Black activists could not overcome the coordinated efforts of white neighbors and elected officials who maintained residential segregation through alternate means.

Political Power and Black Community

Baltimore’s activists included proponents of both the accommodationist and anti-racist approaches to civil rights represented by Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. Many local religious leaders worked to “uplift” Baltimore’s poor Black residents by improving their living and working conditions while still avoiding direct challenges to segregation. Other activists articulated the need to build and support Black institutions by withdrawing from racist white institutions rather than working to change them. While religious groups still dominated civil rights leadership, there was a rise in the number of fraternal organizations and mutual aid groups that also played a role in organizing Black Baltimoreans around a variety of social issues. And, in the early decades of the twentieth century, the fight for women’s suffrage provided a new avenue for civil rights advocacy that ultimately led to increased political power for the Black community.

Uplift Ideology and Community Building: 1890s–1920s

Some Black Baltimoreans responded to racial inequality and widespread racism by investing in education, civic activities, and religious work to “uplift” Baltimore’s poor and working-class Black residents. Historian Kevin K. Gaines has written about “racial uplift ideology” and how it can be interpreted as “an anti-racist argument” used by an educated Black elite. Uplift, Gaines writes, was a “complex, varied and sometimes flawed response to a situation in which the range of political options for African American leaders was limited by the violent and pervasive racism of the post-Reconstruction United States.”33

Rev. George Freeman Bragg is another example of a Baltimorean who believed in the importance of racial uplift. Born in North Carolina on January 25, 1863, Bragg’s childhood was shaped by the Civil War and Reconstruction. Ordained as a deacon in Virginia in 1887, he entered the Episcopal priesthood in 1888 and, in 1891, arrived in Baltimore with a passion for fostering independent leadership within the Black church. He joined the 66-year-old St. James’ Church located at Saratoga Street and Guilford Avenue. In 1901, Bragg led his church to a new building in northwest Baltimore at Park Avenue and Preston Street near the site of the present-day Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. During the early twentieth century, Bragg became a prominent speaker and writer on the role of Black congregations within the white church, Black religious history, and a variety of civil rights issues.

Bragg’s writing reflects the complexities and contradictions inherent to Baltimore’s uplift movements more broadly. In 1904, for example, Bragg joined dozens of other Black pastors in speaking out against the proposed Poe Amendment to disenfranchise Black voters by calling it “an eternal disgrace” and concluding that the amendment “seeks to convert a hitherto quiet and industrious body of people into a state of discontent, and thereby retard the best interests of the whole people.”34 In a 1906 letter to the Sun, Bragg observed that many white judges and police officers were “unconsciously” prejudiced against Black people and argued: “If the negro is uplifted he must be uplifted from within. The man who seeks his reformation must be of the same bone and blood as himself and hopeful to the end of the chapter."35

In his 1904 remarks, however, Bragg also reinforces positive racial stereotypes of Black Americans as “quiet and industrious,” and, in 1906, Bragg offered the most charitable possible interpretation of white prejudice as “unconscious” rather than intentional and explicit. Bragg’s assumptions of white superiority and the necessity of a conciliatory approach to Black uplift are also clear in a 1918 letter where Bragg made the case for recognizing “white people who have helped the colored race,” writing: “Contact of the best of the white race with black people will beget the same likeness in the ebony. Therein is security and peace.”36

While Bragg’s presentation may have been intended to catch the sympathies of the Sun’s white editors and readers, Bragg’s approach to social change surely prompted skepticism among many Black Baltimoreans in the early twentieth century. White Baltimoreans, however, embraced Bragg’s ideas. The 1926 Colored Professional, Clerical and Business Directory noted that Bragg “possesses possibly more strong friends among influential white people of this community than any other colored clergyman.”37

When middle-class Black residents in his congregation continued to move even farther west, Bragg moved St. James again in 1932. The congregation moved to the former Episcopal Church of the Ascension, constructed in 1867, at Lafayette Square (B-4436), where they celebrated their first service on Easter morning. The move reflected a major change in the neighborhood as St. James’ Church was one of four Black congregations that moved to Lafayette Square between 1928 and 1934.38

Republican lawyer Harry S. Cummings also employed the language of “uplift” while serving on the First Branch of the Baltimore City Council.39 Twenty-six-year-old Baltimore-native Harry Cummings was the first Black person to win elected office in Baltimore when he won a seat on the City Council in 1890, representing city’s eleventh ward. It was a narrow win—just a little over 100 votes out of 3,472. Cummings had graduated from the University of Maryland School of Law just a year earlier, and, when the Sun asked his plans after the election, he explained, “I will feel it my duty” to address the “special needs for colored people” especially “better school facilities.”40 In September 1894, Cummings spoke at a “colored people’s fair” organized by the Baltimore County Industrial Association at the Timonium fairgrounds. Then out of office, Cummings spoke on the importance of “morality, religion, frugality, and industry,” arguing “it is our duty to show the world the progress we have made.”41 However, in other settings, Cummings railed against the structural barriers to Black people finding better work; calling out “unfair and unjust restrictions imposed on [black workers].”42 Cummings and his family moved to 1234 Druid Hill Avenue in 1898. The Councilman’s sister, noted educator Ida Rebecca Cummings, continued to live in the house up until the 1950s, but Cummings, his wife Blanche Teresa Conklin and their two children, Louise Virginia and Harry Cummings Jr., moved again to 1318 Druid Hill Avenue in 1911 where Cummings lived up until his death in 1917.43

While unable to overturn the system of segregation, individuals could still work to improve the material conditions of life for themselves, their families, and neighbors. For example, in 1894, Dr. J. Marcus Cargill helped found Provident Hospital—the first hospital in Baltimore employing Black doctors and nurses—with 10 beds located in a small house at 419 Orchard Street. Less than two years later, the hospital moved into a larger house at 413 W. Biddle Street. In the late 1920s, the hospital managed to raise funds to purchase and remodel the former Union Protestant Infirmary building erected in 1859 at Division and Mosher Streets. Albert I. Cassell, a noted Black architect who served as the University Architect for Howard University, drafted plans to remodel the building. Finally, on October 15, 1928, Provident Hospital opened at the new location on Division Street.44 Unfortunately, after the hospital vacated the building for a new facility on Liberty Heights Avenue in the late 1960s, the building suffered a severe fire and the city ordered the building’s demolition in 1972.45

During this period, Black women also took on key leadership roles as both volunteers and paid staff to philanthropic groups and mutual aid organizations. For example, in 1896, a group of Black women in Baltimore founded the Colored Young Women’s Christian Association (CYWCA), joining a national movement gathered under the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs to promote “racial uplift.”46 In 1902, the CYWCA opened a facility in a corner rowhouse at 1200 Druid Hill Avenue.

After the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, Ida R. Cummings and other members of the CYWCA established the Colored Empty Stocking and Fresh Air Circle organized to support Black dependent children.47 The Empty Stocking Circle served as a Black counterpart to a charity led by local white women to make Christmas special for Baltimore’s poor children. The “group hosted events at churches, including St. John A.M.E. Church and Union Baptist Church, and often drew more than 1,000 people. The Freeman reported on the group’s successful fundraising and expanding programs in 1908:

The Colored Empty Stocking and Fresh Air Circle, at Baltimore, which held a street carnival on Druid Hill avenue, Lanvale, Etting and Dolphin streets, last week, have used the proceeds of the sales to purchase a farm on the Emory Groves car line, near Reisterstown. The farm consists of a large dwelling, where the little ones will be entertained during the summer, and ten and one-half acres of ground.48

The Women’s Cooperative Civic League formed in 1913 with a broader mission to “address housing, health, sanitation, and educational problems resulting from the rapid urban growth” in Black neighborhoods. The organization was led by Sara Collins Fernandis, a Black social worker who lived at 953 Druid Hill Avenue for over 17 years. The Civic League divided responsibility for different wards of the city among a core group of volunteers and grew their membership to reach 130 people by 1914.49

A national resurgence of the antebellum lyceum movement led many members of Baltimore’s Black middle class to form literary societies. For example, in 1906, Amelia Johnson and others formed a Baltimore chapter of the Du Bois Circle, a women’s auxiliary created to support the Niagara Movement organized by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Trotter. With a mission of “social uplift and higher literary attainment,” the group organized regular meetings for discussion on both literature and current issues affecting the city’s Black residents. Like the Empty Stocking Circle, literary societies also played a meaningful role in sharing political opinions, providing mutual aid for Black neighbors, and organizing their resistance to Jim Crow in Baltimore during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. As one summary of Baltimore’s civic, literary, and mutual aid associations noted, such groups worked with “limited funds and an all-black membership” and “accomplished much in spite of seemingly insurmountable opposition.”50

In her study of women at Sharp Street United Methodist Church, Felicia L. Jamison attributes the rise of female leadership to their role in raising the money to pay down a $70,000 debt for the new church building the congregation completed in 1898.51 By December 1920, the congregation burned its mortgage documents, then quickly shifted their attention to the construction of the church’s Community House: “a church-affiliated community center that housed young and poverty stricken women, and offered professional classes to the Baltimore black community.”52 A year earlier, in 1919, under the leadership of Rev. M. J. Naylor, Sharp Street Church established a community program that “included a kindergarten, a day nursery, and an employment bureau.”53 The new facility enabled the church to build on this foundation with a new $85,000 community center. The Community House Annual Report for 1921–1922 describes the center’s mission as seeking to “provide a higher civic and social life, to institute and maintain educational and philanthropic enterprises and to investigate and improve conditions generally through co-operation with other social agencies.”54

Uplift and electoral politics were not the only approaches activists employed in this period. Activists also focused on the need to build and support Black communities independent of racist white institutions. Under Rev. Harvey Johnson’s leadership, for example, Union Baptist Church (B-2965) withdrew from the Maryland Baptist Union Association in 1892 in response to unequal salaries for Black pastors and unequal authority for the Black churches belonging to the religious association.55 Five years later, in September 1897, Johnson delivered a speech in Boston, entitled “A Plea For Our Work As Colored Baptists, Apart From the Whites,” that criticized white churches for their failure to acknowledge the equality of Black co-religionists: “Why is the proposition never made to us of the necessity of co-operating in the work of abating the many forms of legal and socially oppressive laws and customs now in vogue all over the country, both North and South?”56

In 1898, Rev. Johnson organized the Colored Baptist Convention of Maryland. Historian Bettye Collier-Thomas has noted Johnson’s close relationship with W. E. B. Du Bois in this period and suggested that Johnson “willingly shared twenty years of experience, strategy development and know-how with the founders” of the Niagara Movement.57 Harvey and Amelia Johnson both used their writing to speak out against racist ideas and the people who sought to promote them. In her introduction to Rev. Johnson’s book, Amelia exhorted Black Americans to “search out, examine, reject and deny the wretched misrepresentations” of Black people as inferior.58

Many activist groups were established during this period, but some proved more difficult to sustain, including two organizations associated with Trinity Baptist Church (B-2970). One example is the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL), first established in 1914 in Ohio by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican-born activist. James Robert Lincoln Diggs, educator and pastor at Trinity Baptist Church beginning around early 1915, helped establish the Baltimore chapter of the UNIA-ACL in 1918, and later presided over Garvey’s 1922 marriage to Amy Jacques Garvey.59 Trinity Baptist Church also hosted the 1920 annual convention for the National Equal Rights League from October 20 to October 22. The conference was presided over by Rev. J. H. Taylor, secretary of the Maryland Association for Social Service, with speakers including founding member Monroe Trotter, lawyer Nathan S. Taylor from Chicago, and Trinity’s own Rev. Diggs.60 By 1922, the UNIA chapter was directed by Rev. J. J. Cranston and had an office at 1917 Pennsylvania Avenue.61

By the 1920s, both organizations were in decline—the National Equal Rights League had lost much of its membership to the NAACP. The UNIA quickly declined in size and prominence after the 1925 arrest of founder Marcus Garvey and his deportation to Jamaica two years later.

Fraternal organizations were an emerging center of political power and organizing. Black fraternal organizations in this period provided economic support for their members, typically in the form of insurance, but also played a critical role in supporting nascent civil rights activism with their large membership. A joint meeting of Black mutual aid societies in Baltimore in 1884 turned out 40 organizations with a combined membership of 2,100 people. By 1900, the city had over 70 mutual aid societies for Black Baltimoreans—groups whose membership dues supported the purchase of halls and meeting spaces, burial costs for members, and social events throughout the year.62 One example is Baltimore’s chapter of the United Order of Moses located at 527 Orchard Street. Established in 1868, the United Order of Moses had chapters in cities throughout the country. Some of these groups shared space with political organizations, such as when the Samaritan Temple at Calvert and Saratoga Streets hosted a “Colored Republican Mass-Meeting” in June 1884.63

Party Politics and Voter Disenfranchisement: 1900s

Black political power in the late nineteenth century was undermined by the racism of the local Republican Party and gerrymandering by the Democratic Party to limit the influence of Black voters. Black voters made up a small share of Baltimore’s total even after the addition of Black women to the pool of eligible voters following the ratification the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Outside of Baltimore City, the Democratic Party used a variety of strategies to illegally disenfranchise white and Black Republican voters. In November 1901, the Sun reported how “fully ten thousand ballots of legitimate voters” had been “thrown out on the most frivolous excuses.” For Baltimore City, however, pre-printed ballots meant only few ballots were “thrown out on the account of disfiguration or other inaccuracies.”64 Closer scrutiny by members of the Republican City Committee and Black voters may also have played a role in limiting the flagrant violations of voter’s rights found elsewhere in Maryland.

Disenfranchisement efforts spread across the country after Mississippi passed a new state constitution in 1890 that disenfranchised Black voters (the so-called “Mississippi Plan”), by creating barriers to voter registration and firearm ownership. White legislators and voters in Delaware, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri all enacted similar policies around this time.65 Frustrated by their electoral defeat in 1895, Maryland Democrats sought to undermine the Republican Party by disenfranchising Black voters. Maryland voters went to the polls three times in the early 1900s to consider the issue and vote on the Poe Amendment (1905), the Strauss Amendment (1908) and the Digges Amendment (1910), all of which threatened to eliminate the right to vote for thousands of Black Marylanders by restricting the right to vote based on ancestry and property ownership.

A coalition of Black activists and recent European immigrants worked together under the banner of the Maryland Suffrage League to defeat all three proposals. Although Black women were not yet allowed to vote, the disenfranchisement campaigns drew just as strong opposition from women as from men. In 1905, Rev. Alexander at Sharon Baptist Church (B-4441) at 1373 Stricker Street wrote to the Afro-American calling for Black women to join the fight:

We also appeal to colored women to do their part. The advocates of the Poe-amendment are urging the white women to help them and since the object of the amendment is to deprive colored men of civil and political liberties, colored women ought to do what they can to defeat it.66

A mass meeting of around 100 women at the Perkins Square Baptist Church (later demolished for the construction of George B. Murphy Homes) in October rallied opposition to the amendment.67 White Republican party leaders, including prominent Baltimore lawyer Charles J. Bonaparte, also played a role in rallying opposition to these proposals. Historian Jane L. Phelps noted Bonaparte’s opposition to the Poe and Strauss Amendments in 1905 and 1908.68 Ultimately opponents to the disenfranchisement campaign succeeded, defeating the Poe Amendment with 104,286 to 70,227 votes in 1905 and the Strauss Amendment 106,069 to 98,808 votes in 1908. An even more definitive vote defeated the Digges Amendment by a margin of 38,000 votes in 1910.69

While the campaigns against Black voter disenfranchisement prevailed, the influence of Black voters on local electoral politics was still limited. In 1900, Black men made up 15% of the voting-age population and 15% of registered voters. By 1932, Black men and women made up 16% of the population but only 12% of the registered voters.70 It is notable, however, that Black representation was never absent from the Baltimore City Council in the 1910s and early 1920s, as Black voters in the city’s Fourteenth and Seventeenth wards elected a series of Black Republicans to the City Council including Harry S. Cummings, Warner T. McGuinn, and Walter Emerson.71

Suffrage and Black Women Organizing: 1890s–1920s

The ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 marked a new era for the civil rights movement in Baltimore and around the country. However, winning the right to vote was just one of the ways that Black women grew in power and visibility as activists and organizers during this period. The opportunities Black women won through their own activism and political victories helped shape the movement throughout the twentieth century.

The Black women advocating for women’s suffrage encountered unique challenges. Following the 1890 merger of the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the national suffrage movement began to systematically exclude Black women in a bid to win more support from Southern white women and political leaders. The growing segregation of the suffrage movement encouraged the organization of independent groups for Black women, beginning with the Colored Women’s League in Washington, DC, in June 1892. In 1896, the Colored Women’s League merged with the National Federation of African American Women to form the National Association of Colored Women.

A number of white-led suffragist organizations, including NAWSA led by Carrie Chapman Catt and the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (later known as the National Woman’s Party) led by Alice Paul, sought to build support for women’s suffrage among southern white political leaders by arguing that suffrage for women would not challenge the white supremacist agenda of disenfranchising Black voters.72 Maryland suffragists similarly faced stiff opposition among state legislators. Local white women’s suffrage groups, such as Bassie Ellicott’s Equal Suffrage League of Baltimore and Emma Maddox Funck’s Maryland Suffrage Association, supported the continued disenfranchisement of Black women voters in Maryland. For example, in March 1909, white Baltimore suffragist Edith Houghton Hooker hosted a meeting where Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, president of the NAWSA, spoke. The Sun reported:

That all the leaders in the movement for woman suffrage do not extend their desire for women to vote to include all “colored sisters” was made evident last night by the two most conspicuous figures at the meeting of the Equal Suffrage League of Baltimore, in Friends’ Meeting House, on Park Avenue.73

During the 1912 campaign for a statewide bill to grant women’s suffrage in Maryland, an editorial in the Afro-American observed how white women sought to deny suffrage to Black women calling it a “play to the galleries seeking to catch the favor of a few Negro haters in the legislature at Annapolis.”74

Black women, however, would not be excluded from politics or civil rights activism. In 1906, reflecting on the organization of the “Federation of colored women of Baltimore and in the State of Maryland,” J. T. Jenifer wrote to the Afro-American to argue that the organization, “will be a combined moral handmaid in the influence and aid of the Suffrage League, Niagara Movement, and Civic Councils, in every effort against jimcrowism, disenfranchisement and in every effort in race redemption, civil rights and uplift.”75 Black women also organized to support the Republican Party in 1911, as the Afro-American reported:

For the first time in the political history of Maryland, the Negro women of the city have been organized into a campaign committee for the purpose of working for the success of the Republican ticket.

A new “Auxiliary Republican Committee” met at 414 W. Hoffman Street. The group, chaired by Rev. Ernest Lyon, former US Ambassador to Liberia and minister at Ames Methodist Episcopal Church, allied with the Anti-Digges Amendment League, an organization of “several hundred Negro women” led by president Eliza Cummings, mother of City Councilman Harry S. Cummings.76

In response to this pattern of exclusion by white suffrage organizations, Estelle Hall Young, a Black civic reformer, founded the Woman’s Suffrage Club in 1915. Young had studied under W. E. B. Du Bois in Atlanta and later moved to Baltimore and married Dr. Howard E. Young, a prominent Black pharmacist. The Young household lived at 1100 Druid Hill Avenue, close to club leaders Margaret Gregory Hawkins and Augusta T. Chissell who lived in neighboring houses at 1532 and 1534 Druid Hill Avenue. In December 1915, the Woman’s Suffrage Club held the first in a series of mass meetings at Grace Presbyterian Church with activist Alice Dunbar as the featured guest speaker. The club continued to host public meetings at local churches, using advertisements in the Afro-American to publicize their events.77

When the House of Representatives voted on an earlier version of the women’s suffrage amendment in 1915, four members of the Maryland delegation voted against the proposal citing the enfranchisement of Black women as the rationale for their opposition.78 In 1919, when the Senate considered the Nineteenth Amendment, Maryland’s Senators split over the issue with the state’s Democratic Senator voting against and the Republican Senator voting in favor. When the measure came before the Maryland legislature for ratification on February 24, 1920, it was rejected again due to opposition to granting Black women the vote. Despite Maryland’s rejection of the measure, the Nineteenth Amendment won support in 36 states, and, with the amendment’s approval in Tennessee on August 18, it became part of the US Constitution on August 26, 1920.

Black Baltimoreans quickly turned to the task of registering women to vote that fall. The Women’s Suffrage Club held weekly meetings at the YWCA at 1200 Druid Hill Avenue urging Black women to register at the polls on the earliest possible date: September 21, 1920. Estelle Young saw voting, in part, as one way to challenge the prejudice deployed against Black women during the recent suffrage debate, saying:

We women are especially bitter against the type of white politicians who said that we would not know a ballot if we saw one coming up the street. We must register in order to vote, and we must vote in order to rebuke these politicians.79

On November 2, 1920, women voted for first time in Maryland, and, in 1921, the Women’s Suffrage League of Maryland affiliated with the recently formed League of Women Voters of the United States.80

Homes and Neighborhoods

Once evenly distributed throughout the city, by the turn of the twentieth century Baltimore’s Black population had concentrated into segregated Black areas. As Black households were displaced by industrial and commercial development in the downtown areas and excluded from growing suburban districts, distinct Black neighborhoods emerged in older neighborhoods west and east of downtown.

Development of a Segregated Black Community: 1880s–1900s

Baltimore’s dramatic political and social changes during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century not only coincided with, but, in large part, promoted the residential segregation of Black residents and the creation of segregated Black neighborhoods. Even as late as 1880, the city’s Black population could be found distributed evenly over three-quarters of Baltimore’s 20 wards and eight districts. By 1890, however, the largest share of Black Baltimoreans lived in the Eleventh Ward, an area roughly contained within the present boundaries of W. Franklin Street, Park Avenue, Preston Street, and Myrtle Avenue, where over 11,000 of the 21,269 residents were identified as “colored” (making the ward over 50% black). By 1904, the city’s Northwestern District (which included the Eleventh Ward) held more than 40% of Baltimore’s over 81,000 Black residents.81

The movement of Black households was in part due to their displacement for the expansion of the B&O railroad yards around Camden Station in the 1900s, the development of War Memorial Plaza east of Baltimore City Hall, and the construction of Preston Gardens on St. Paul Street in the 1910s, among other projects. Black households that could afford to move to northwest Baltimore also were able to avoid the poor housing and sanitation conditions found in the city’s older neighborhoods around the harbor. At the same time, in the fast-growing suburban neighborhoods at the edges of the city, builders sold houses with the implicit or explicit promise of excluding Black residents. This sprawling suburban development was made possible by the expansion of electric streetcar service in the 1890s and 1910s, the creation of a much-needed new sanitary sewer system in 1915, and the annexation of a large area of Baltimore County in 1918.

Reduced demand from white households created an opportunity for Black households looking to move into previously segregated areas. Anne McMechen, attorney George McMechen’s wife, later explained her family’s aspirations for their purchase of a McCulloh Street house: “we wanted to be more comfortable—a right I think everyone has to exercise.”82 Black Baltimoreans who could afford to move left the formerly “aristocratic St. Paul street section,” south Baltimore, and east Baltimore for the northwest area.83 The Old West Baltimore Historic District (B-1373) encompasses much of the area sought after by affluent and middle class Black residents during this period.

Historian Willard B. Gatewood described Baltimore’s “relatively well-to-do… aristocracy of color,” writing:

A black editor calculated in 1890 that about twenty individuals in the city’s black community collectively represented a wealth of approximately $500,000. The wealthiest, John Locks, was said to be worth $75,000. Many of those included in Baltimore’s black economic elite derived their wealth from catering, barbering, hod-carrying, brick-making, and caulking. … Many of these individuals invested in real estate, so that by the turn of the century their heirs were often among the wealthiest blacks in the city.84

The depth of this Black middle class is illustrated by the numbers of lawyers, business owners, educators, school administrators, religious leaders, and civic organizations listed in the first edition of the Colored Business Directory published by Robert W. Coleman in partnership with his wife, Mary Mason, beginning in 1914.

Industrial and commercial development around the harbor, the destruction of over 1,500 buildings in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, and the city’s subsequent work to widen downtown streets also contributed to the displacement of Black residents in the city center. Rev. Levi Coppin, pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church from 1881 to 1883, called out the condition around their 1847 sanctuary in 1881: “Bethel could not remain indefinitely in Saratoga St., among the iron foundries and hold a leading place among the Churches.” The congregation ignored its pastor’s entreaties to move until 1909 when the city condemned their building to make way for a wider Saratoga Street forcing the church to relocate to northwest Baltimore in January 1911.85 In contrast to Bethel’s delayed move, some residents experienced more sudden and brutal displacements. In 1905, the B&O Railroad began buying up property in the area surrounding Camden Station.86 Two years later, in June 1907, after a court injunction blocking the demolition of a three-story tenement at 912 Sharp Street ran out, the B&O Railroad gave the Black residents just 30 minutes notice before they started tearing down their building.87

White landlords in the newly segregated Black neighborhoods in northwest Baltimore extracted as much rent as they could from the growing number of Black tenants. In January 1915, the Afro-American reported on the premium white landlords charged. The account suggested that Black tenants on Argyle Avenue, Myrtle Avenue, and McCulloh, Lanvale, and Stricker Streets all paid at least 20% more than the white households that had previously lived there. Black residents looking to buy a home had their own unjust obstacles to overcome including exploitative rent-to-own schemes. The Afro-American concluded their report on segregation and housing conditions for Black Baltimoreans, with the observation: “A restricted residence area for the race tickles the whims of some of the whites, makes other whites rich and impoverishes the colored people who have, like the Jews in Russia, to live within the pale.”88

Similar to those Black residents moving into homes formerly occupied by white households, Black congregations moved into formerly white churches. After their displacement on Saratoga Street, for example, Bethel A.M.E. Church moved into the 1868 building of St. Peter’s Protestant Episcopal Church (B-123) located at Druid Hill and Lafayette Avenues. The speakers at the opening services included William T. Vernon, an A.M.E. church leader and Republican-appointed Register of the Treasury, who spoke on the “Birth of a New Freedom,” declaring: “What the Negro desires in this country is the same law to govern him as govern the white man, or in other words, a square deal.” The next address came from James P. Matthews, an old member of the St. Peter’s congregation that originally erected the church, reflecting on the “uptown” movement of white and Black churches and reassured the assembled congregation that the City Council’s efforts to enact a segregation ordinance would not be able to exclude members who sought to “acquire homes within easy reach of the church.”89

A smaller number of congregations built new sanctuaries using services from white builders and architects. Examples include St. Peter Claver Catholic Church (B-4443), built at Fremont and Pennsylvania Avenues in 1888, and Union Baptist Church (B-2965), built on Druid Hill Avenue in 1905. Sharp Street Church (B-2963) purchased an existing church at Dolphin and Etting Streets but then tore it down in 1892 to erect the new building that still stands today.

| Year of move | Church | Prior location | New location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1888 | St. Peter Claver Catholic Church | Calvert and Pleasant Streets | Fremont and Pennsylvania Avenues |

| 1898 | Sharp Street Church | Sharp and Pratt Streets | Dolphin and Etting Streets |

| 1901 | St. James Episcopal Church | Lexington Street and Guilford Avenue | Park Avenue and Preston Street |

| 1905 | Union Baptist Church | Guilford Avenue between Saratoga and Lexington Streets | Druid Hill Avenue and Dolphin Street |

| 1911 | Bethel A.M.E. Church | Saratoga and Gay Streets | Druid Hill Avenue and Lanvale Street |

Table: Examples of Black congregations relocating to northwest Baltimore.

By the late 1920s, the area occupied by Black residents, churches, and schools in west Baltimore included most of the neighborhoods now known as Madison Park, Upton, Druid Heights, Harlem Park, and Sandtown-Winchester. In 1926, the Afro-American recalled the rapid changes residents had witnessed since the beginning of the century:

The Baltimores’ “Who’s Who” has been constantly moving northwest in the city during the last 25 years… Although a few prominent families still live in the South and Northeast Baltimore, the bulk of the population now resides in that section of the city known as Northwest Baltimore. […] Oxford and Orchard streets once housed many of Baltimore’s colored four hundred. Even Sara Ann Street, now one of the most dilapidated and one of the worst streets in the entire city, once boasted the names of now prominent families.90

In east Baltimore, a similar transition took place in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In 1929, the white Episcopalian Church of the Holy Innocents sold its building to the Black Grace Baptist Church (B-5145-4) and, in 1931, Baltimore’s oldest Black Roman Catholic congregation—St. Francis Xavier—purchased the 1867 Madison Square M.E. Church (B-3973).91

Excluding Black Tenants and Homeowners: 1890s–1920s

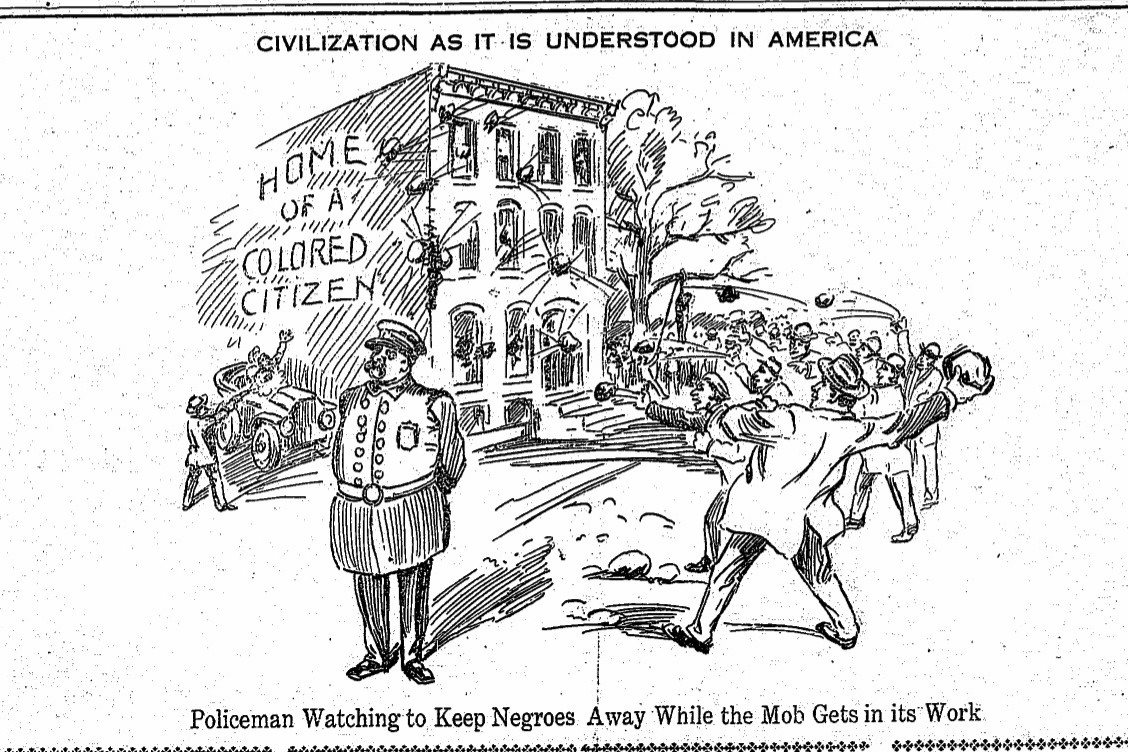

White residents, elected officials, and developers used a wide variety of approaches to create and maintain segregated white neighborhoods. When mob violence proved an inadequate deterrent, white residents demanded municipal segregation ordinances to enlist help from the police in excluding Black owners and tenants. When Black lawyers used the courts to overturn the segregation ordinances, white property owners turned to restrictive covenants and exclusion through physical design. These and other approaches were difficult for Black activists to overcome and turned housing segregation an intractable challenge throughout the twentieth century.

White Violence and Racial Segregation Ordinances: 1890s–1917

The many documented examples of attacks on Black households in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries suggest that physical violence played an important role in the exclusion of Black residents from many Baltimore neighborhoods.92 One early documented incident took place in late August 1899. Just one day after John Lang, a 55-year-old Black construction worker, and his family moved to 1805 Druid Hill Avenue, crowds of white boys and young men threw a barrage of stones and bricks at the back the building. The attack broke all of the home’s rear windows and forced Lang’s wife and children to “shut themselves in a room” for safety.93 The Lang household was the only “colored” family on the block (the next nearest Black family reportedly lived south of Lanvale Street).

The attack followed sustained efforts by local leaders to encourage opposition to Black housing opportunity and political power. Just a few months earlier white Democrats in the Fourteenth Ward had rallied at nearby Solmson’s Hall on Fremont Avenue where participants heard William B. Redgrave open the meeting by complaining about the “dismal atmosphere” of “negro domination,” and Charles C. Rhodes, a local lawyer and magistrate, claiming that the growth of the city’s Black population threatened to “depreciate the value of property.”94

Attacks on homes owned or occupied by Black households continued in the early 1900s and 1910s. In May 1902, after Black tenants rented a home at 1705 Druid Hill Avenue, assailants smashed three of the front windows with potatoes and poured cans of sticky tar onto the home’s white marble steps and window sills.95 In September 1910, similar attacks took place at 1802 and 1804 McCulloh Street. In September 1913, a group of white men attacked the house 1324 Mosher Street one day after a Black family moved in. The attack provoked a crowd of young Black men to respond in kind by throwing stones at other nearby houses and the ensuing fight resulted in the injury of five people (including a police officer).96 The attacks likely continued, in part, because the police rarely intervened and the penalties for white residents who assaulted Black neighbors were light to non-existent. For example, in 1911 two young white men in southeast Baltimore encountered a Black man, Lacy Stubling, sitting in a doorway at 18 S. Spring Street, called him a racial slur, and then beat him “almost into insensibility.” One was sentenced to 30 days in jail and the other only 20 days.97

For years, white advocates of racial segregation had sought to pass legislation to make it illegal to rent or sell to Black households in areas of existing white occupancy—and, of course, to enlist the police in enforcing the law. On December 19, 1910, Mayor James Preston signed this long-sought policy into law, making it the first municipal law to require racially segregated housing in the United States. Known commonly as the West Ordinance after Councilman Samuel T. West who fought for the policy, white residents in northwest Baltimore began advocating for the bill just weeks after W. Ashbie Hawkins purchased a house at 1834 McCulloh Street and rented it to his law partner George F. McMechen. The new ordinance prohibited Black Baltimoreans like McMechen from buying or living in houses on blocks like the 1800 block of McCulloh Street where a majority of existing occupants were white. It further prohibited white Baltimoreans from moving into blocks that were largely black.98

Within a month of the bill coming into effect, 26 cases were brought before local courts. While most of these cases involved Black people seeking to move to excluded blocks, a few involved white residents. One white woman, Mrs. Kate Koller, was charged in January 1911 after she moved to 602 Arch Street, despite having lived in the house next door for several years. Reportedly, the complaint was made by “colored residents in the block” possibly seeking a fair application of an unfair law and potentially to highlight the absurdity of the policy.99 According to historian Bruce Thompson, in the very first case to reach the courts, the judge “ruled that the law was invalid because it was drawn incorrectly.”100

After the first ordinance was overturned, the City Council passed a second segregation ordinance on April 7, 1911. However, the Council quickly identified a potential legal issue with the law, so they replaced it with yet another segregation ordinance on May 15. The new law was entitled:

an ordinance for preserving peace, preventing conflict and ill feeling between the white and colored races in Baltimore city, and promoting the general welfare of the city by providing, so far as practicable, for the use of separate blocks by white and colored people for residences, churches and schools.101

In June 1913, W. Ashbie Hawkins, a local Black lawyer living at 529 Presstman Street, went to court to defend Rev. John H. Gurry, the Black pastor of King's Apostle Holy Temple. Gurry faced criminal charges for moving his church to 581 Laurens Street—what the police called a “white block” under the segregation law. In June, Hawkins won Gurry’s case and overturned the segregation ordinance again.

Undeterred, the City Council passed yet another replacement segregation in November 1913. It wasn’t until four years later, in 1917, that the US Supreme Court decision in Buchanan v. Warley overturned a similar ordinance in Louisville, Kentucky, and ruled municipal segregation laws unconstitutional.102 According to historian Dennis Halpin, Black Baltimoreans’ “resistance to the ordinances remade the city’s racial geography.” However, white residents also persisted in their efforts and Black activists “struggled to challenge the strategies segregationists used in the wake of the laws’ demise.”103

Deed Restrictions and Exclusion by Design: 1890s–1920s

Deed restrictions, racist practices by professional realtors, and racialized urban design and planning (described by some as “clearance and containment”) all contributed to the persistence of segregation even after the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision. Historian Dennis Doster suggests that the national NAACP’s later advocacy around residential segregation has roots in their legal fight over segregation in Baltimore.104

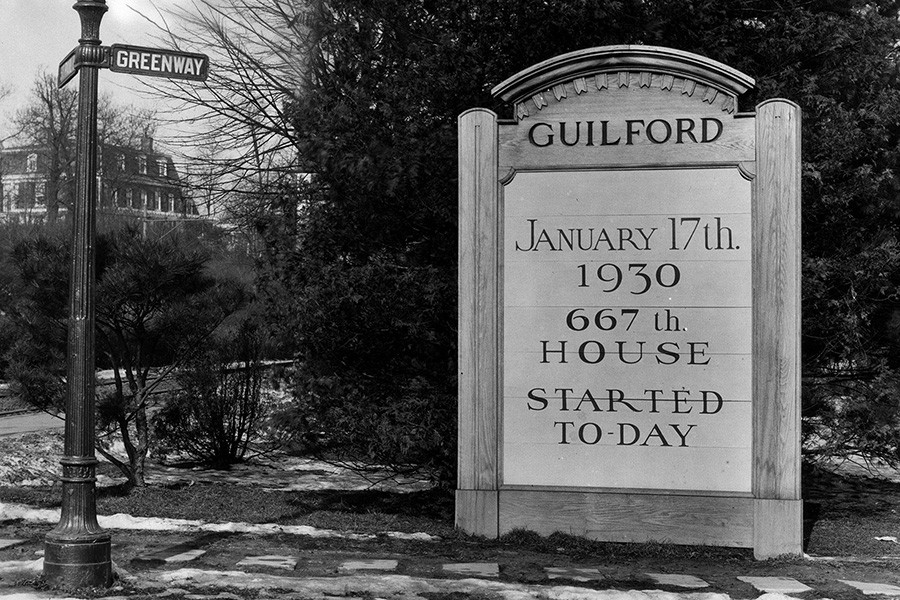

Outside of the exceptional cases of Morgan Park and Wilson Park, local builders and developers almost never erected new homes for Black buyers in the first half of the twentieth century. Indeed, builders selling new homes to white Baltimoreans proudly advertised deed restrictions that prohibited Black people from buying or occupying property within their development. In other cases, white residents organized to encourage neighbors to sign covenants and pressure property owners to refuse to sell or rent to Black households. Some of the city’s most notable examples of racial exclusion are the neighborhoods built by the Roland Park Company, including Roland Park (B-136, established in 1891), Guilford (B-3654, established in 1913) and Homeland (B-1336, established in 1924).

Historian Paige Glotzer has studied how the Roland Park Company “used deed restrictions as the cornerstone of a broader attempt to manufacture a dichotomy between suburban and urban space in order to sell a new spatial and social arrangement to a status-conscious white middle class.”105 Ultimately, these north Baltimore neighborhoods served as models of racial exclusion for developers nationwide. Home developers around the country regularly requested copies of the restrictions as they sought to emulate the Roland Park Company’s approach to racial exclusion. Glotzer credits the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) with supporting the national distribution of discriminatory practices. For example, in 1924, the revised NAREB code of ethics explicitly prohibited realtors from “introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individual whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.”106

When deed restrictions were not enough to isolate white communities, the Roland Park Company also established physical boundaries between its developments and nearby properties occupied by Black Baltimoreans. For example, the company planted “a long hedge to cut off sightlines of a predominantly black settlement down the hill” before later placing a “sewage disposal field” at the same location.107 Evidence of exclusion by design is still visible in Baltimore where physical barriers and one-way streets separate the neighborhoods of Homeland and Guilford from the predominantly Black neighborhoods on the east side of York Road.

Many older neighborhoods in Baltimore could not create new physical barriers like the Roland Park Company, but they could use racial covenants. In January 1924, 200 members of six west Baltimore “protective associations” met to fight the movement of Black households into their neighborhoods. Residents gathered at Fulton Avenue Presbyterian Church located at Fulton Avenue and Monroe Street and listened to Dr. C. P. Woodward, Councilman for the Fifth District, defend the necessity of exclusionary organizations:

The principal function of any organization is to acquire everything of benefit to the community and to keep away everything undesirable. It is a pity that law-abiding citizens who do not receive sufficient protection from the law to keep out undesirables must form protective associations to do so.108

The meeting sparked a campaign to seek signed commitments promising to refuse all Black buyers from 1,600 property owners in the blocks bounded by North Avenue, Pennsylvania Avenue and Bentalou Street. The Afro-American summarized the sentiment at the meeting: “Negroes should be put in a bag and pitched overboard.”109

The racist panic by their white neighbors prompted Black Baltimoreans to renew organizing efforts but to limited effect. A new Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance was formed with a meeting on January 14, 1924, at Union Baptist Church. The group established a “civic committee” led by Rev. D. G. Mack to aid in a “crusade against segregation.”110 That same month, the state legislature established a new Inter-Racial Commission with a mix of 13 white and eight Black members “to consider legislation concerning welfare of the colored people of Maryland.”111 From the outset, however, Black critics saw the commission as an inadequate response to the city’s challenges. In February, the Afro-American called out the Inter-Racial Commission for their “dominant desire… to preserve good feelings between the races” that led the members to avoid any statement explaining “plainly whether it is for or against segregation.” The editorial concluded that the ongoing efforts by white residents to prevent “Negro invasion” as a “phase of segregation” even “more insidious and dangerous than an effort to legalize it for it is being nurtured and kept alive by the worst kind of racial hatred.”112

Proponents may have relied on violence and racial hatred because their efforts to use the courts to promote segregation were less successful. For example, in 1918, a group of white residents in Lauraville attempted to have the circuit court in Towson revoke the 1917 sale of the Ivy Mill property to Morgan College (formerly the Centenary Biblical Institute, now Morgan State University). The court dismissed the case. Lauraville residents appealed but the state court upheld the lower court’s decision.113 The Morgan Park (B-5316) neighborhood next to the new campus slowly developed into a Black residential neighborhood with homes for Morgan College faculty and administrators along with notable individuals including W. E. B. Du Bois and Dr. Carl J. Murphy.114

Morgan Park wasn’t the only Black community developed in northeast Baltimore. The development of nearby Wilson Park began in 1917, when Harry O. Wilson Sr., a wealthy Black businessman and banker, purchased several parcels of land in northeast Baltimore near Cold Spring Lane and the Alameda (some of which had already been subdivided by the Huntingdon Building Company). Wilson advertised in the Afro-American offering 200 lots and six cottages “with all conveniences,” including hot water, heat, electric lights and large front porches, available in a community “open to our race.” Building lots started at $300 and completed cottages were listed for $1,600.115 For a wealthier group of Black residents, Wilson Park became an elite enclave. By the 1920s, Wilson Park homeowners included lawyers William Ashbie Hawkins, George W. F. McMechen, and Rev. Garnett Russell Waller, the national NAACP’s first vice-president and Wilson’s father-in-law.116

Urban Reform Efforts and the Great Migration: 1900s–1920s

In the early twentieth century, participants in a growing urban reform movement—including both white- and black-led community groups concerned about housing, sanitation, public health, and social conditions—began to explore new approaches to addressing racial and class inequalities. The Great Migration of Black Americans from rural communities in the south to northern cities prompted debates over how to address the poverty and poor housing these new residents experienced. In New York City, these pressing concerns inspired a group of reformers to establish the Committee on Urban Conditions Among Negroes (later known as the National Urban League) on September 29, 1910.

Concern around urban housing and sanitation centered, in part, on the risk of contagious diseases such as tuberculosis. The local interest in these issues is illustrated by the white-led housing reform efforts focused on conditions in segregated Black neighborhoods in the 1890s and 1900s. Streets and Slums: A Study in Local Municipal Geography (1892) by Frederick Brown was the first in a series of influential studies on the relationship between housing, health, and municipal policies. Two years later, in 1894, Carroll D. Wright, a white statistician who served as the US Commissioner of Labor between 1885 and 1905, submitted a report to Congress titled The Slums of Baltimore, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. Most famously, in 1907, a white social worker, Janet Kemp, wrote a report entitled Housing Conditions in Baltimore for the Association for the Improvement of the Condition of the Poor and the Charity Organization Society.117

In contrast to northern and Midwestern cities, like New York, Chicago, and Cleveland, where the Great Migration brought large numbers of Black migrants from the deep South, Baltimore was largely a destination for Black migrants from Maryland and Virginia. In 1910, 87% of the city’s Black population was native to Maryland and migrants from Virginia made up the largest share (8.7%) of those born outside of the state. In 1920, the share of native Marylanders declined to 76%, but was still a sharp contrast with Detroit’s 8.4% or Manhattan’s 20.9% of native-born Black residents. Even in 1930, at the outset of the Great Depression, 59.4% of Baltimore’s Black population was born in Maryland.118

White-led reform efforts paralleled, and, at times, responded to Black efforts to address both poverty and discrimination among the city’s Black residents. In 1891, the Brotherhood of Liberty hosted a public meeting with William A. Hunton, the first Black YMCA executive in the United States. By 1893, local organizers succeeded in establishing Baltimore’s Colored Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).119 The organization grew and erected the Druid Hill Avenue Branch of the YMCA at 1609 Druid Hill Avenue in 1919.120

In the spring of 1898, Rev. Ernest Lyon, pastor of the John Wesley Methodist Episcopal Church and resident at 141 W. Hill Street, delivered a paper, “Mortality Among Colored People,” before the city’s newly formed Ministerial Union to “agitate for the improvement of the condition of the colored people.” Lyon linked the problem of mortality among Black residents in Baltimore to “the unsanitary condition of the section in which they live… inhabited almost exclusively by colored persons.” Lyon argued the city health department took “little pains to give the streets and houses proper attention” in areas occupied by Black residents.121

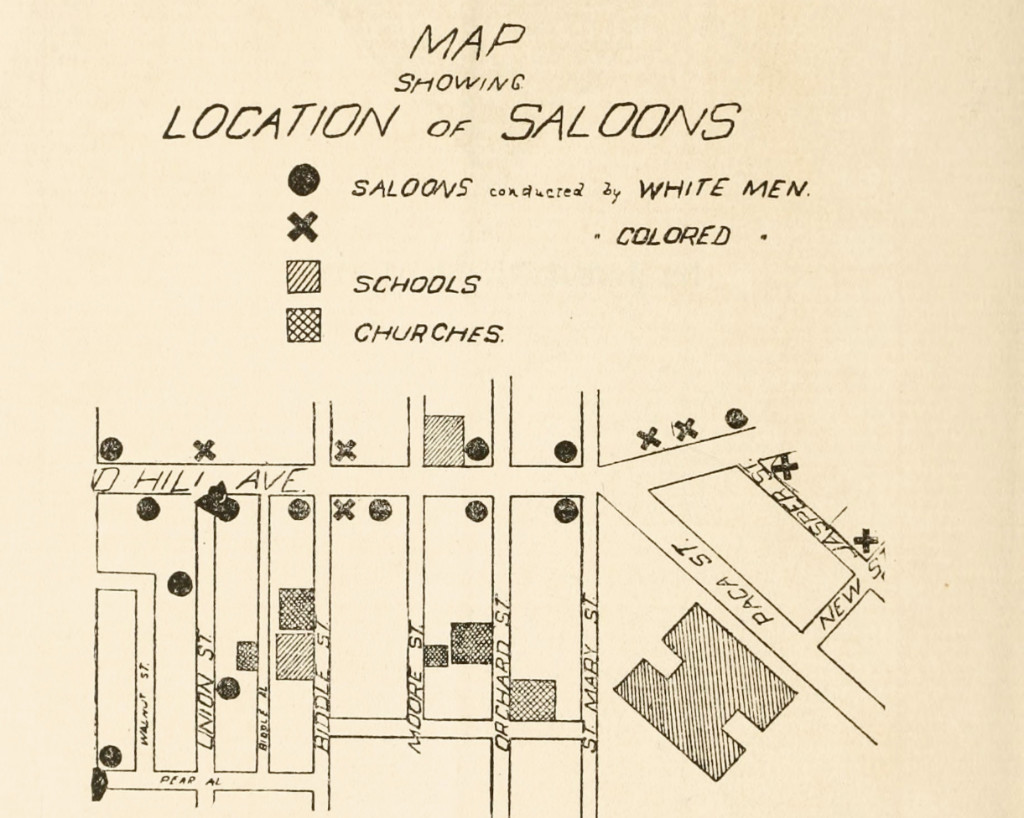

In 1906, inspired by a 1904 exhibition on tuberculosis in Baltimore that highlighted the concentration of cases in the segregated district in northwest Baltimore, a group of prominent Black lawyers, doctors, ministers, educators, and business leaders established a new organization known as the Colored Law and Order League. Led by Dr. James H. N. Waring, a Black physician and principal of the Colored High School, the group conducted a study looking at the effect of saloons, many owned by white operators, located in close proximity to Black schools in west and east Baltimore. In 1908, the group presented their findings to reformers and religious ministers, including the Ministerial Union and the Colored Ministerial Union. The group described how implicit and explicit discrimination by the Baltimore police and the Liquor License Board had enabled the poor conditions in many Black neighborhoods to develop.122

Challenging Employment Discrimination: 1880s–1920s

In the same 1898 speech where he decried the poor housing conditions for Black Baltimoreans, Rev. Ernest Lyon also observed how the “exclusion of the colored men from labor organizations” forced Black workers to accept low wages making it even more difficult to purchase decent food and housing. The issues of housing and neighborhood conditions at the center of late nineteenth and early twentieth century reform efforts were closely related to employment discrimination. Prejudice by white employers, segregated unions, and a range of official and unofficial policies barred Black men and women in Baltimore from a wide range of public and private employment opportunities.

White elected officials not only avoided any effort to limit racial discrimination against Black workers, white Democrats even exploited racist anxieties over integrated workplaces as a means to undermine support for Republicans among white voters. In October 1889, while considering an ordinance to regulate hiring by the city commissioner’s office, the City Council only narrowly avoided adding an amendment by Councilman D. Meredith Reese to limit employment to “white citizens” only. In explaining his proposal, Reese opposed “mingling white and colored men in work,” arguing the “colored workman is not equal to the white workman,” and, when his colleagues questioned the constitutionality of the amendment, Reese argued that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to Baltimore City.123

Discrimination in public employment was uniquely frustrating to Black Baltimoreans after a Republican mayoral administration took office in 1895. Despite Black voters making up an estimated one-third of the city’s Republicans, by 1898, the only Black workers appointed by Mayor Alcaeus Hooper were three Black street department superintendents who supervised segregated teams of Black laborers. A sharp editorial in the Afro-American pointed out the striking contrast with the six or seven hundred white people appointed to city jobs.124

Most Black workers in Baltimore and many other cities had been excluded from the broader national labor movement. One of the few national unions for Black workers, the Colored National Labor Union, collapsed around 1871 and no other group had replaced it. One difficulty for Black workers was segregation of local union chapters. One of the few unions to challenge this in Baltimore was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) whose members started organizing Black longshoremen on the east coast in 1917 during World War I. Ben Fletcher, a Black labor leader and organizer for IWW from Philadelphia, organized dockworkers in Baltimore in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Unfortunately, Fletcher was arrested in Pennsylvania and held until 1923.125 Despite such setbacks, current and former IWW members remained active in Baltimore through the Marine Workers League for several more years.126

In the early 1920s, the Baltimore Urban League emerged as one of the most important organizations addressing the issue of employment discrimination. Before Baltimore’s local chapter was officially established, a committee of residents requested assistance from the National Urban League’s Department of Research and Investigations. Beginning in March 1922, the national organization conducted a three-month study of local industry that documented the discrimination and exclusion that Black workers encountered in Baltimore. A full one-third of the 175 industrial plants surveyed for the study (a total of 62 plants employing 20,735 people) refused to hire any Black workers.127