The 50-year period between the early 1830s and mid-1880s set the foundation for Baltimore’s long civil rights movement. Varied social movements sought to secure freedom, provide mutual support, and encourage self-determination for Black Baltimoreans. At the same time, the development and spread of racist ideas before and after the Civil War laid the cultural and political foundation for segregation and disenfranchisement in the late nineteenth century. Moreover, these racist ideas shaped the work of white abolitionists along with Black educators, religious leaders, and activists—many of whom adopted an assimilationist approach that sought to “uplift” Black Baltimoreans to the assumed superior state of white Baltimoreans. Only a few directly confronted the role of white supremacy and racial discrimination in dividing working people and undermining their ability to challenge the political and economic interests of large property owners and established white political authorities in the decades before and after the Civil War.

European colonists in the Maryland Colony established the Town of Baltimore, Jonestown, and Fells Point in the early 1700s. Baltimore City incorporated between 1796 and 1797, uniting these three settlements. By the early nineteenth century, free and enslaved Black people turned the city into a precious refuge in a Chesapeake region dominated by oppressive white supremacy. The city was a place where Black people organized and worked to seek freedom from slavery and self-determination. In the city, these men and women organized to build independent Black churches, such as Sharp Street and Bethel A.M.E Churches, and to open schools for Black children who were excluded from the segregated public schools the city opened in 1826. By 1831, over 10,000 enslaved people and over 17,000 free people of color lived in Baltimore.

Following Nat Turner’s August 1831 rebellion in Southampton, Virginia, however, the reaction of white slaveholders threatened the safety and independence of this growing community. During the rebellion, Nat Turner traveled through the area encouraging enslaved people to join him and killing white slaveholders and their families before the rebellion was suppressed by a local militia. In retribution, white slaveholders killed approximately three dozen Black individuals without a trial, until the local militia stepped in to make mass arrests.1 Maryland’s slaveholders panicked, envisioning similar violent slave insurrections led not by enslaved people, but by the state’s free Black residents. The state legislature swiftly enacted repressive laws placing new strict limits on the rights of both free and enslaved Black Marylanders.

Black residents in Baltimore resisted. They pushed back against the publicly funded Maryland Colonization Society, a group that sought to transport free Black Marylanders to west Africa; petitioned Baltimore City to establish public schools for Black students; and protested the exclusion and discrimination experienced by Black workers. In the Supreme Court’s notorious 1854 Dred Scott decision, when Maryland native and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and six other justices ruled that “the enslaved African race” and free people of color could make no claim to freedom or citizenship under the US Constitution. Former Marylander Frederick Douglass joined thousands of other Americans, including Black Baltimoreans known and unknown, in protesting the decision by risking their own lives and freedom to help enslaved people escape the South and, after 1854, the United States along the Underground Railroad.

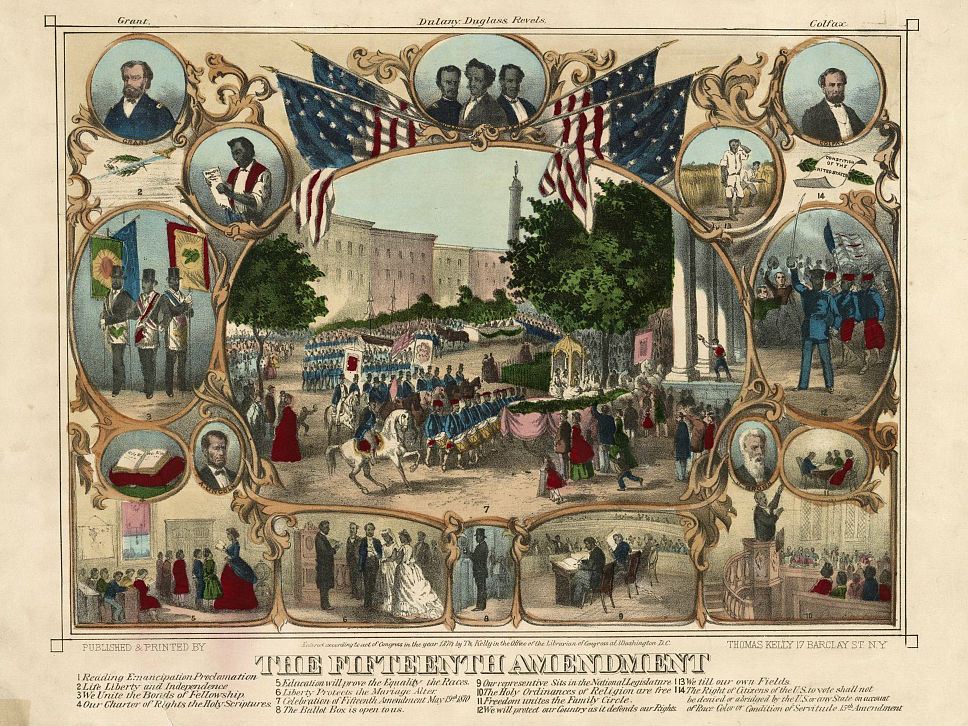

The onset of the Civil War in 1861 marked a new beginning for Black Baltimoreans seeking greater freedom for themselves and their neighbors. Hundreds of free Black people in Baltimore supported the Union army by working on fortifications and hospitals around the edges of the city. Over 8,000 enslaved Marylanders enlisted in the US Colored Troops between the spring of 1863 and the end of the war two years later. White Union supporters drafted a new constitution in 1864 that proposed to abolish slavery and disenfranchise Marylanders who fought for the “so-called ‘Confederate States of America,’” or gave “any aid, comfort, countenance or support to those engaged in armed hostility to the United States.”2 After a narrow vote of Maryland residents in October 1864 approved the new constitution, slavery in Maryland officially ended 222 years after enslaved Africans were first held in slavery at St. Mary’s City in Southern Maryland. In the politically turbulent period after the end of the Civil War, the nation adopted the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution in 1867 giving all Black Marylanders the right to equal protection under the law, and the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, giving Black men the right to vote.

These new legal and political rights empowered an emerging community of Black activists—a group that included religious leaders, labor organizers, and many Union army veterans who settled in Baltimore after the end of the war. Black congregations, Republican political clubs, fraternal and mutual aid organizations, and the Colored Convention Movement all helped structure the community of men and women fighting for freedom and justice for Baltimore’s Black residents. Some Black and white activists focused their work on the religious and educational “uplift” of the newly freed people arriving in Baltimore after the end of the Civil War. Aspiring Black teachers could enroll for training at the Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of Colored People, established on Courtland Street near Saratoga Street in 1865, or at the Centenary Biblical Institute, established at Sharp Street Church in 1867.3 Increased access to education among Black residents also created new demands for skilled employment. In the 1870s and 1880s, Black educators, religious leaders, and other supporters pushed Baltimore City to begin hiring Black teachers for the city’s segregated colored schools.

Even the moderate proponents of racial “uplift,” however, found little support from the state’s white politicians, judges, and community leaders. After the Civil War, white political leaders across the state, including many who had supported or fought for the Confederacy, stoked racist fears and anxieties to undermine the rising political power of their Black neighbors. Just three years after the abolition of slavery, a new state constitution in 1867 changed the rules for legislative representation to allow white legislators associated with the openly white-supremacist Democratic Party to dominate the Maryland General Assembly. Through speeches and publications, they presented nascent civil rights activism in Baltimore as impossible and dangerous due to their belief in the inherent inferiority and criminality of Black Marylanders. White leaders used racist ideas to justify police violence and inequality in criminal justice—topics that emerged as major concerns for Black Baltimoreans in the 1860s and 1870s. When Black Republican party activists sought to influence the selection of candidates within their own party, white Republicans pushed back by manipulating primary elections. Outside of Baltimore, Democrats excluded Black voters from the polls and redrew local districts to diminish Black voter influence on elections.

Black Life in Baltimore Before the Civil War

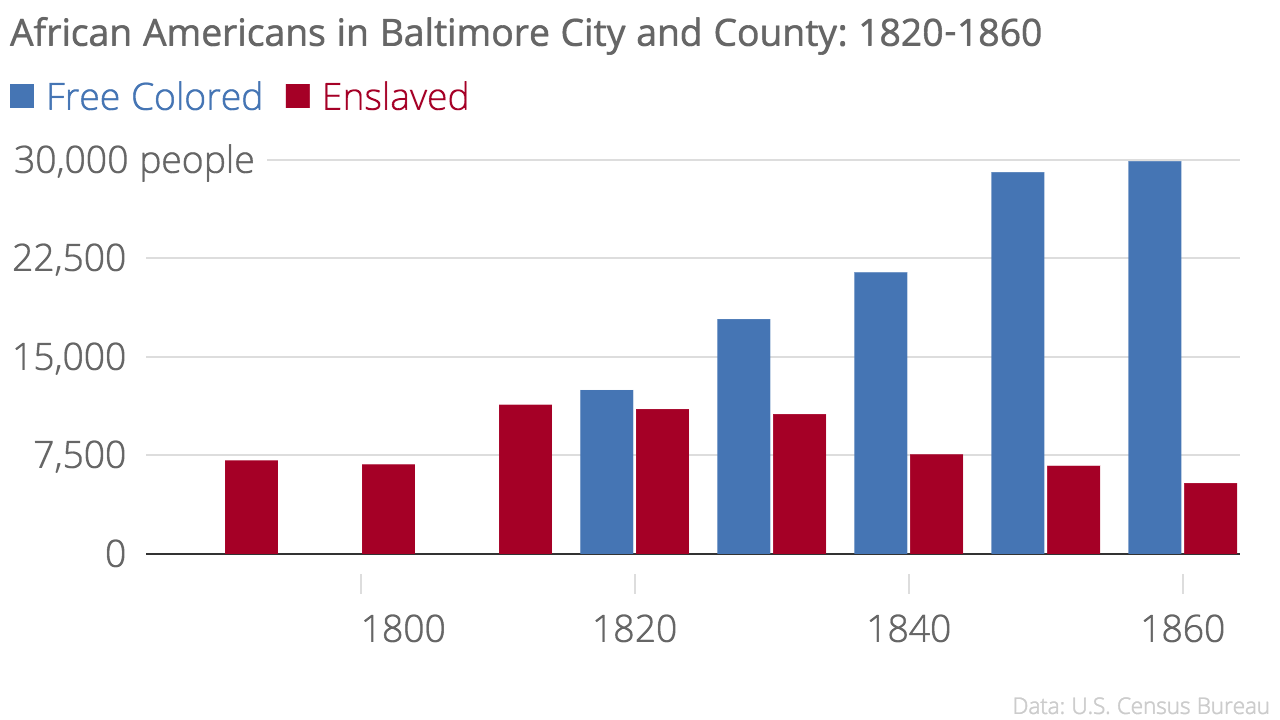

Baltimore grew quickly in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Between 1790 and 1820, the city nearly doubled in population and then doubled again by 1840. Enslaved and free Black workers were key to this early growth. Black men and women who built and repaired ships in Fell’s Point, washed laundry in alley house courtyards near the harbor, dug clay for bricks from pits in South Baltimore, cared for other people’s children in Mount Vernon mansions, and swept streets in the Western Precincts around today’s Lexington Market. In the early 1800s, free Black people outnumbered enslaved people, making Baltimore the only place in the state where most Black people were free.4 In the 1820s and 1830s, Black residents, both free and enslaved, were about one quarter of the city’s residents.

Initially, the city’s free Black population concentrated around the harbor and Fell’s Point—close to shipyards, docks, and warehouses where they found work in the region’s booming maritime economy. Very few free Black households had the wealth or opportunity to acquire property. By 1798, only eight had acquired real estate making up just (3.3% of the all Baltimore real estate owners). The average value of their real estate was just $226 compared to $1,4791 for white-owned real estate.5 This deep disparity only grew worse during the early nineteenth century.

The growing population of free people of color in Baltimore followed the broader growth in the free Black population in Maryland. Since the late eighteenth century, changing agricultural practices around the state and declining profits for tobacco farms led to an increasing use of manumission to free thousands of enslaved people.6 After 1810, the total number of enslaved people in Maryland began a long decline. The proportion of free people grew from 27% of the state’s Black population in 1820 to over 40% in 1840.

By 1830, over one-third of the state’s free Black people lived in Baltimore. In the city, they could find work and educational opportunities largely unavailable elsewhere in Maryland. New arrivals from the Eastern Shore and Southern Maryland joined the existing community of Black churches and social groups and helped them grow in both size and influence.7 Baltimore offered free and enslaved men and women the opportunity to earn wages—wages that often went to purchase their own freedom or the freedom of family members. Historian Seth Rockman explained, “When slaves gained some control over the wages they earned, freedom was typically not far behind.”8

The distribution of Black residents changed as the city center saw the development of more rowhouses for affluent white residents. In 1810, almost half of Baltimore’s free Black residents lived near the center of the city. But, by 1830, less than 10% resided in that area. Historian Christopher Phillips described how Black residents rented “cheap tenement housing” on the west side of the city. Proximity to the city’s white population was a practical requirement for Black residents working in white households but most free Black people occupied houses in the “maze of alleyways and court-yards” where “black family dwellings interspersed with those of laboring and poor whites.” For example, in 1820, hundreds of free and enslaved Black households lived in small houses on narrow alleys including Happy Alley, Argyle Alley, Straw berry Alley, Petticoat Alley, and Apple Alley in or near Fells Point; Union Alley and Liberty Alley in Old Town; Bottle Alley, Whiskey Alley, and Brandy Alley in the center of the city; and Welcome Alley, Waggon Alley, Dutch Alley, Sugar Alley, and Honey Alley to the west and south.9

By 1850, Black property owners made up just 0.4% of the city's free Black population and 0.6% of the city's total population. Evidently, even this small group must have been seen by some white Marylanders as a threat—given the failed attempt in the state legislature to pass a law prohibiting free Black residents from buying real estate or leasing a property for more than a year. In 1856, there were only 236 Black property owners in the city.10

Free Black activists in the period included George Alexander Hackett who was born free in 1806, and, as a life-long member of Bethel A.M.E. Church, became a prominent activist in the 1840s and 1850s.11 Black caulker and labor organizer Isaac Myers was born free in 1835, and, as a child, attended a day school run by Rev. John Fortie, who, a generation earlier in 1787, had left Lovely Lane Methodist Church to form the Colored Methodist Society with Caleb Hyland.12

Enslaved people in Baltimore faced the same threats of brutal violence and family separation experienced by other enslaved Marylanders. At the same time, however, the large population of free people of color in Baltimore and the varied opportunities for Black workers gave many enslaved people a chance to make a better life. Frederick Douglass later recalled the “marked difference” in the 1820s between his experience with slavery in southeast Baltimore and on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, writing:

A city slave is almost a freeman, compared with a slave on the plantation. He is much better fed and clothed, and enjoys privileges altogether unknown to the slave on the plantation.13

However, any privileges enjoyed by free and enslaved Black Baltimoreans over Black men and women living in other areas of the state remained severely limited. White artisans excluded free Black workers from craft apprenticeships and employers relegated Black workers to the most difficult, dangerous, and lowest-paying jobs in the city.14 Free Black men and women living in Maryland could not vote and could not testify in a criminal trial or a freedom suit.15 Baltimore’s public schools first opened in 1826, but Black children could not attend public school even as their parents paid taxes that went towards their construction and operation.16 In 1827, pro-slavery candidates swept local and national elections making the preservation and expansion of slavery the cornerstone of the national Democratic Party.17

Repression in Baltimore after Nat Turner’s Rebellion: 1830s–1850s

The early 1830s marked a critical turning point in the earliest history of the civil rights movement in Baltimore. Following Nat Turner’s rebellion in Southampton, Virginia, in August 1831, Maryland slaveholders panicked over reported rumors in the Niles’ Weekly Register and the Baltimore American of impending revolts in Maryland reflecting what historian Sarah Katz described as “the frenzied fear among whites that the nation’s slaves were prepared to rise up in a violent bid for freedom.”18

In response, the Maryland state legislature established a committee led by Henry Brawner, a slaveholder from Charles County in Southern Maryland. Brawner’s committee developed a proposal to expand funding for colonization, restrict manumissions, and undermine the rights of free Black Marylanders.19 In May 1832, the legislature approved the committee’s proposal including a prohibition to stop free Black people from moving to Maryland from another state or from returning to Maryland after taking a job elsewhere. The new law prohibited free Black Marylanders from owning firearms without a certificate from county officials or buying alcohol, powder, or shot. African Americans could no longer hold religious meetings unless a white minister was present, with the exception of Black congregations in Baltimore City.20 By end of the 1830s, Maryland had enacted laws to effectively re-enslave free Black people by allowing courts to sentence them to a term of servitude for debts, “vagrancy,” or certain criminal convictions.21

As this pattern of oppression continued into the 1840s and 1850s, many Black Baltimoreans left Maryland for free northern states, like Pennsylvania, Ohio, or New York, or for Black communities in Canada. Significantly, the size of the city’s Black population hardly changed at all between 1840 and 1860. Baltimore had transformed from “a place of refuge to one of repression,” observed historian Christopher Phillips.

Building Independent Black Congregations and Institutions: 1830s–1850s

The second quarter of the nineteenth century was a time of great religious fervor and social change. The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival that led many congregations to evangelize and recruit free and enslaved Black members. While predominantly an evangelical movement led by Methodists and Baptists, the religious revival fostered a host of reform movements including temperance, women’s rights and the abolition of slavery. The relationship of Black Baltimoreans to this movement was complicated. While many Black leaders advocated for greater freedoms through newly formed organizations, many others were forced to work within an oppressive system to seek incremental reforms.

In resistance to the severe restrictions on Black life in Baltimore and Maryland, local Black abolitionists, church leaders, and activists led efforts to oppose colonization and protect the rights of free Black Baltimoreans. The strong local opposition to colonization came, in part, thanks to the way that free and enslaved Black Baltimoreans could build communities in ways they could not in many other Southern towns and cities. In Virginia, for example, an 1806 law required newly freed African Americans to leave the state after manumission.22 In Maryland, many Black residents stayed and built congregations.

Baltimore’s Black churches provided education and civic and community meetings for adults that made the church into a platform for political action.23 The city’s growing Black population in the early and mid-nineteenth century supported the growth of both existing Black churches and the foundation of new churches and religious organizations. Black parishioners also struggled against repressive white religious institutions from the inside.

One of the earliest Black congregations in the city was Sharp Street Church, which was established in 1787 and initially worshipped in the gallery of the Old Lovely Lane Chapel on German Street. In 1802, the congregation built their own church between Lombard and Pratt Street (where the Baltimore Convention Center is located today), serving both free and enslaved Black residents. The church operated a school and served as a meeting location for various advocacy groups.24 Despite the success of this large and influential congregation, Sharp Street Church was stymied in their efforts to secure independent Black leadership. As noted by historian J. Gordon Melton, through the 1820s, Sharp Street, along with Asbury, was considered an African church attached to the Baltimore charge. In 1832, the two churches were set aside as the “African Methodist Episcopal Church in the City of Baltimore” and incorporated as a single entity, but they still had a white minister, Joseph Frey. Frustrated by this, the Sharp Street congregation annually petitioned the Baltimore conference to assign a Black preacher to lead the congregation, but the petition was consistently ignored. In response to this lack of action, beginning in 1848 “black Methodists from Sharp Street and other Black congregations began to lobby for the organization of an all-black Conference to include the churches in the care of the Baltimore Conference.”25

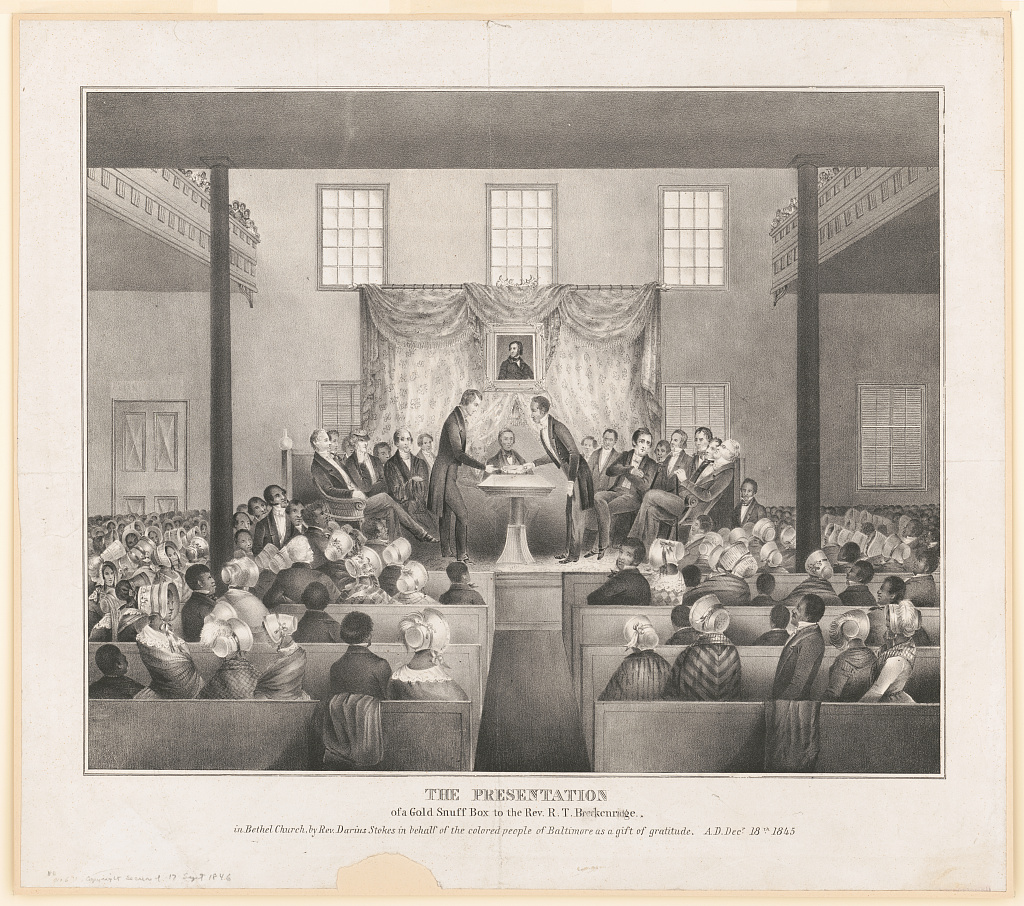

Around 1815, a group of Black Methodists established the African Methodist Bethel Church Society (now Bethel A.M.E. Church) and, in 1817, bought a building on Saratoga Street near Gay Street from a white abolitionist named John Carman.26 George Hackett and the members of the Moral Mental Improvement Society, “considered one of the city’s leading literary and debating societies” met at Bethel A.M.E. Church on the first Sunday of every month, highlighting the important link between religious and social institutions.27 Historian Christopher Phillips noted the role of social institutions in Baltimore between 1790 and 1860:

Rather than overt organized opposition, Baltimore’s free Black residents sought to strengthen their social institutions, by which to provide by example—both to themselves and to white residents—that they were worthy of equal treatment.28 Historian Stephen Whitman similarly argued how by building Black institutions and making “claims to respect as fellow Christians,” Black Baltimoreans made a “a visible and sometimes successful challenge to the ideology of black inferiority and pointed to the possibility of a stable multi-racial society, proslavery and colonizationist claims to the contrary.”29

Not all Black religious groups could afford the risk of a direct challenge to established white religious authorities. One example of this is the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the first Black Catholic religious order for women in the United States. The order was established in 1828 by Mother Mary Lange and Marie Magdaleine Balas—two French-speaking Black women who came to Baltimore along with many other Black and white migrants from the Caribbean following the end of the Haitian Revolution in 1804. Historian Diane Batts Morrow observes that the early sisters “did not directly protest their marginal social status” and “functioned within the parameters of racial discrimination sanctioned by the church.”30

The Oblate Sisters formed on June 13, 1828, and opened a School for Colored Girls with 11 boarding students and five day students gathering in a rented residence at 5 St. Mary’s Court. The building also served as the convent for the sisters as they made the education of children of color their own defining mission.31 By July 2, 1829, the group moved to a second rented residence at 610 George Street. Even as they worked to educate Black children, the Sisters accepted discriminatory policies imposed by white Catholic Church leadership, although not without frustration. Such policies included burial in a racially segregated cemetery and segregated seating in chapel pews (the Sisters “evidently agonized” over the decision to accept this seating rule imposed by white church leaders in 1837). The group sought to find a difficult balance as they “acceded to socially sanctioned racial discrimination” while they simultaneously “resisted real and potential threats to their status as women religious.”32

As with the example of the Oblate Sisters, operating schools for Black students was a major area of focus for Black religious communities and, in some cases, sympathetic white allies. In 1797, a group of Black Methodists supported by the Maryland Society for the Abolition of Slavery, a Quaker abolitionist group, opened a school and meetinghouse on Fish Street (now Saratoga Street) but lack of funds forced the group to leave the building within just a few months. By 1801, the group had arranged funds for a “convenient house for the accommodation of the members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church” in Baltimore, and, in 1802, created a meetinghouse on Sharp Street than became known as the African Academy.33

In 1807, Daniel Coker founded the Bethel Charity School on Sharp Street with the sponsorship from the Colored Methodist Society of Baltimore and, by 1817, operated the school from Bethel A.M.E. Church on the south side of Saratoga Street east of Holliday Street where Coker served as pastor. William S. Watkins succeeded Coker as the church schoolteacher after Coker’s emigration to West Africa in 1820.34

In 1826, the Maryland General Assembly authorized the creation of the Baltimore city school system for white children under the age of 10 and the first school, known as Public School No. 1, opened on September 21, 1829. Public Schools No. 2 and No. 3 (also for white students only) opened soon after and by the end of the year, enrolled 269 students.

Black families recognized the injustice of being forced to pay school taxes that supported white-only schools, and Black leaders in Baltimore petitioned the city government to provide either tax relief or schools for Black children. These petitions were presented in 1839, 1844, and 1850 (which included signatures from 90 Black and 126 white Baltimore residents). Despite the interracial support, the mayor and City Council rejected every one of these petitions.35 In 1859, Noah Davis, pastor at Saratoga Street Baptist Church, observed:

The large colored population of Baltimore, now from thirty to forty thousand souls, have no sort of Public School provision made for them, by the city or state governments. They are left entirely to themselves for any education they may obtain.36

Despite the exclusion from public schools, Black Marylanders sought education—often through the city’s growing churches. By the 1850 Census, over half of Maryland’s Black residents identified as literate to some extent.37 By the late 1850s, Baltimore had 15 Black Protestant congregations with over 6,000 members. Church Sunday schools had nearly 3,000 people in regular attendance.38

The activism, politics, and beliefs of Baltimore’s Black residents were informed and inspired by Black activists across the state and nation—organized through abolitionist groups and fraternal organization as well as schools and churches. Between the 1830s and the 1890s, the “Colored Convention” movement organized state, regional, and national meetings giving Black leaders a platform to “strategize about how they might achieve educational, labor, and legal justice.”39 For example, in 1830, Hezekiah Grice, a Baltimore butcher, began appealing to Black leaders in the north to hold a national meeting—an appeal that led to the founding the American Society of Free Persons of Color, the sponsoring organization for the much of the Black national convention movement between 1830 and 1835.40 Baltimore also hosted several regional and national meetings between the 1840s and 1860s—including the first regional conference for Black Methodists at Sharp Street Church (1846), the Maryland State Convention of Free Colored People (1852), the State Colored Convention of Maryland (1862), and the Colored Men’s Border State Convention (1868). These gatherings were critical to the development of Black politics before and after the Civil War. Through the research and documentation created by Colored Conventions Project, Dr. Gabrielle Foreman has demonstrated how convention speakers called for “community-based action that gathered funds, established schools and literary societies, and urged the necessity of hard work in what would become a decades-long campaign for civil and human rights.”41

Resistance to the Colonization Movement in Maryland: 1830s–1863

Supporters of the American Colonization Society in Maryland first established a statewide organization in 1827 when a group of loosely organized regional and county societies united. The Maryland General Assembly awarded the new group an annual grant of $1,000 to transport free Black Marylanders to the American Colonization Society’s settlement in Liberia. When the group sent only 12 emigrants to Liberia in 1828, the state terminated its appropriation the following year. Support for colonization was renewed following Nat Turner’s Rebellion in August 1831, leading the state to restore funding with a larger appropriation of $10,000 a year for 20 years to resettle free Black Marylanders in West Africa.42

Black Marylanders reacted strongly to the state’s efforts to expel them. Historian Christopher Phillips recounts Black resistance to the efforts by the Maryland Colonization Society, noting:

The pervasively hostile sentiment against colonization throughout the period and the equally persuasive demeanor of the Baltimore junto forced the Maryland Colonization Society to abandon recruitment effort on the state’s Western Shore.43

Black activists could clearly see the prejudice and racism that drove the state’s resettlement campaign. Colonization was an effort by white Americans who sought to resolve fears over the nation’s free Black population by transporting Black Americans to new colonies in West Africa. While the colonization movement found some support among Black religious leaders, many recognized the racist belief in Black inferiority that drove the movement. In 1831, writer, educator, and minister, William S. Watkins writing in William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator described colonization as deportation and argued that white supporters of colonization sought to strengthen slavery by arguing that "our natural color" is an "obstacle to our moral and political improvement." Instead, he and other Black Baltimoreans would “rather die in Maryland under the pressure of unrighteous and cruel laws” than be “driven, like cattle” to Liberia.44

The Maryland State Colonization Society’s belief in Black inferiority is clearly illustrated in a resolution from the group’s 1841 convention that bluntly stated, “the idea that the colored people will ever obtain social and political equality in this State is wild and mischievous; and by creating among them hopes that can never be realized, is at war with their happiness and improvement.”45 Consequently, between 1832 and 1841, only 50 individual emigrants sponsored by the Maryland State Colonization Society came from Baltimore. In the 20-year period between 1831 and 1851, the society sent only 1,025 emigrants to West Africa—less than one-fifth of the total of 5,571 recorded manumissions in Maryland during the same period. The latter figure likely understates the total number of enslaved people freed in that period as not all slave owners filed manumission documents.46

Not all Black Baltimoreans opposed colonization. Most famously, Daniel Coker, the founding pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church, emigrated to Liberia in 1820. But even differences of opinion over colonization helped shape a distinct local Black identity. Christopher Phillips writes:

[The] conflict over colonization offered black Baltimoreans the opportunity to further the evolution of their own community as distinct and autonomous… Whether for or against colonization, Baltimore’s black community unified around a principle far more compelling; racial progress. Baltimore’s black society became, in the words of one historian of urban African Americans of the antebellum North, a “community of commitment.”47

The representatives of the Maryland Colonization Society heard the opposition from the very outset of their efforts. The society’s membership and leadership included some of the state’s most prominent residents (a number of residences associated with those individuals are still extant in the greater Baltimore region). In 1838, the society’s traveling agent John H. Kennard reported to the board of managers summarizing his understanding of Black opposition to colonization:

They are taught to believe, and, do believe, that this is their country, their home. A Country and home, now wickedly withholden from them but which they will presently possess, own and control. Those who Emigrate to Liberia, are held up to the world, as the vilest and veriest traitors to their race, and especially so, towards their brethren in bonds. Every man woman and child who leaves this country for Africa is considered one taken from the strength of the colored population and by his departure, as protracting the time when the black man will by the strength of his own arm compell those who despise and oppress him, to acknowledge his rights, redress his wrongs, and restore the wages, long due and inniquitously withholden.48

Organized Black resistance to colonization helped stunt the colonization movement before the Civil War, and also laid the groundwork for further advocacy efforts in the years after the Civil War. As before, much of this resistance took place in Black churches, such as Sharp Street and Bethel A.M.E. Church, as well as in the homes of free Black residents and around the city’s wharves and piers where the colonization ships launched for West Africa. Ultimately, the Maryland State Colonization Society ended active operations in 1863, shortly after the beginning of the Civil War.

Escape from Slavery in Baltimore Before and During the Civil War

The struggle for freedom by enslaved Americans changed over the course of the first half of the nineteenth century. Agricultural trends, including a reduced reliance on tobacco cultivation, led to an increase in the manumission of enslaved workers and a growing free Black population. The rise of an organized abolition movement led to new social pressure within some white religious communities to free enslaved people. Black and white Marylanders participated in the Underground Railroad, a loose network of individuals who assisted fugitive slaves in their flight to northern free states. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 only encouraged Underground Railroad efforts and further heightened tensions between slaveholders and abolitionists. The Civil War ultimately brought freedom to all enslaved Americans, but the fight for civil rights for free and newly emancipated Black Baltimoreans was just beginning.

Abolition and Manumission in Early-Nineteenth-Century Baltimore: 1800s–1830s

In the early nineteenth century, slavery in Maryland began to change in significant ways that supported the growth of the state’s free Black population. Importantly, an increasing number of farms stopped cultivating tobacco with enslaved labor. Instead, many farms turned to growing grain and produce, less labor-intensive crops that relied more on the labor of European immigrants than enslaved Black people. Seeing diminishing profits in holding large numbers of enslaved people, rural slaveholders, especially in western and central Maryland, began to manumit, granting legal freedom to hundreds of people they had held in bondage. As the Maryland State Archives notes:

In the state’s northern and western counties, farmers became increasingly dependent upon diversified agriculture, in which slavery played a diminishing role. On the Eastern Shore, soil exhaustion and declining tobacco prices forced farmers to abandon tobacco, manumit their slaves, and cultivate their farms with free black and white farmhands.49

Many members of the state’s growing free Black community supported the emancipation of their family, friends, and neighbors who continued to be held in slavery—sometimes saving money to purchase the freedom of a family member or assisting a friend in escaping to Pennsylvania, New York, or Canada.

Another factor that contributed to the rising number of manumissions and the growth of abolition in Baltimore was the movement by the Society of Friends (better known as the Quakers), and, to a more limited extent, the Methodist Church, to advocate against the slave trade and slave holding more generally. For example, in 1778, Maryland Quakers “called on one another to free their bondsmen and abjure slaveholding.”50 From the late 1700s up through the Civil War, Quaker meetinghouses in Baltimore City, and other Quaker settlements in central Maryland, played a critical role in promoting abolitionist sentiment and in providing support for enslaved people to escape on the Underground Railroad. One notable early Quaker opponent of the kidnapping of free people of color in Baltimore was Elisha Tyson. Tyson reportedly helped secure freedom for hundreds of enslaved people—a contribution recognized by the 3,000 Black people who joined his funeral procession in 1824.51 Tyson’s summer home still stands in the Stone Hill Historic District (B-1319) in the Hampden area.

Between 1800 and 1860, the proportion of slaveholders among Baltimore City residents declined, the share of Baltimore’s total population held in slavery also declined, and the share of the Black population living in freedom grew. Nearly one-third of city residents held at least one enslaved person in 1800. But by 1850, only about 1% of the city’s white population were slaveholders. Enslaved people made up 9% of the city’s population in 1790, under 2% in 1850, and barely 1% in 1860. A small minority of the city’s Black population, just 20%, was free in 1790. By 1830, over 75% of the same population was free and over 90% was free in 1860.52 This large free Black population, and the limited freedoms they had secured, led to stronger, and more organized, advocacy efforts than were possible in other areas with a large enslaved population.

While Quakers stood out among white Marylanders for their opposition to slavery in the nineteenth century, other white Christians supported Black co-religionists in some circumstances. Due to the Methodist Church’s support for abolition, enslaved and free Black people in Maryland often either joined or affiliated with it. Outside the city in Baltimore County and other nearby counties, Black Methodist churches became the nucleus of rural communities that were critical to the success of the Underground Railroad. For example, in 1853 a free Black community in Cecil County near Pennsylvania erected the Howard Methodist Episcopal Church in Port Deposit (the building was later demolished in 1981). Other examples of early-nineteenth-century, free Black communities in Baltimore County include: Glen Arm (BA-3094) around the Waugh Church (BA-540), where services began as early as 1829 (the first chapel was constructed in 1849); the Piney Grove community (BA-3087) around the surviving Piney Grove United Methodist Church (BA-1177) built in 1850; and, the Troyer Road community (BA-3093) that formed around the Mount Joy African Methodist Episcopal Church (BA-2101) and the Union United Methodist Chapel (BA-2100)—both congregations were established between 1850 and 1877.53

Despite the support of some Methodist churches and Quaker meetings, supportive white abolitionists remained a small minority in the Baltimore area and in Maryland. Two notable white abolitionists in early-nineteenth-century Baltimore were Benjamin Lundy, who helped establish the Maryland Anti-Slavery Society in 1825, and William Lloyd Garrison who joined Lundy in 1829 in publishing the abolitionist newspaper, The Genius of Universal Emancipation.54

Historian and Black abolitionist William Still observed the challenges facing enslaved Black people attempting escape through Baltimore in his 1872 book, The Underground Railroad:

Baltimore used to be in the days of Slavery one of the most difficult places in the South for even free colored people to get away from, much more slaves. The rule forbade any colored person leaving there by rail road or steamboat, without such applicant had been weighed, measured, and then given a bond signed by unquestionable signatures well known. Baltimore was rigid in the extreme, and was a never-failing source of annoyance, trouble and expense to colored people generally, and not unfrequently to slave-holders too, when they were traveling North with ‘colored servants’ … But, not withstanding all this weighing, measuring and requiring of bonds, many travelers by the Underground Rail Road took passage from Baltimore.55

Despite these challenges, Baltimore provided freedom seekers significant advantages. Natural geography and transportation routes both supported activist efforts to turn Baltimore city into a hub for fugitives headed toward the Susquehanna River and Wilmington, Delaware, where abolitionists like Thomas Garrett waited to assist, or north through Baltimore County.56 Within the city, railroads were one important part of the infrastructure for escape. The Pratt and Charles Street Depot for the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad saw hundreds of fugitives pass through on their escape north, including Henry “Box” Brown, who escaped from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1849; William and Ellen Craft, who escaped from Georgia in 1848; and, most famously, Frederick Douglass.57 Douglass escaped from slavery in Baltimore on September 3, 1838, by boarding a train to New York City. In 1850, the extant President Street Station (B-3741) building on President Street was erected and likely played a role in other similar escapes up through the Civil War.

The significant resistance white and Black abolitionists encountered in Maryland only grew from the 1830s through the 1850s. Historian Sarah Katz described how fear of “slave revolts” following Nat Turner’s rebellion in Southampton, Virginia, led to a crackdown on abolitionist organizations:

Exaggerated reports of slave revolt alarmed Baltimore in 1831; so did a fear of abolition societies. Many supporters of slavery thought the antislavery movement encouraged insurrection. … Some Baltimoreans went so far as to accuse abolitionist societies of holding midnight military drills to prepare blacks for insurrection.58

In addition to restrictions on the movement of Black Marylanders, the state delivered severe penalties for anyone caught assisting enslaved people in an escape. One notable example was Charles Turner Torrey. In 1842, Torrey organized an Underground Railroad route from Washington to Baltimore, Philadelphia and Albany, New York. He moved to Baltimore in late 1843, and, in June 1844, was arrested and confined to the Maryland Penitentiary where he died of tuberculosis on May 9, 1846. A memoir telling the story of his life and death inspired action from abolitionists throughout the United States and Europe.59

Abolition and the Underground Railroad after the Fugitive Slave Act: 1850–1861

In 1850, the US Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which required that all local and state governments in northern states must fully cooperate with slaveholders seeking to re-enslave people who had escaped from slavery in Maryland and other states where slavery remained legal. The new law made escape an even more dangerous proposition for enslaved people and life for free Black men and women difficult as they could be kidnapped and forced into slavery. Earlier paths to emancipation through self-purchase, or purchase by family members, were increasingly undermined by slaveholders who fraudulently broke term slavery agreements to maximize their own profit. As a result, historian Stephen Whitman explains, enslaved Black Marylanders “more and more frequently took the long odds of winning freedom through flight.”60

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, pushed by Southern slaveholders to stem the flow of enslaved people moving north to freedom, led to expanded efforts by abolitionists to support the Underground Railroad, as well as to growing violence on both sides. Baltimore was no exception. In 1851, for example, Baltimore County slaveholder Edward Gorsuch and several others were wounded seeking to recapture four enslaved men who had escaped to the farm of abolitionist William Parker in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The event became known as the Christiana Riot (also known as the Christiana Resistance) and sparked an even deeper commitment to militant resistance among abolitionists.61

Baltimore and Maryland slaveholders called on the Baltimore police, as well as local police and courts in northern states, to support their efforts to recapture escaped enslaved people. Historian William T. Alexander observed a “remarkable” growth in the “activity and universality of slave hunting” under the new law, citing the example of a Baltimore police officer who killed William Smith, an alleged fugitive in Pennsylvania, while attempting an arrest:

The needless brutality with which these seizures were often made tended to intensify the popular repugnance which they occasioned. In repeated instances, the first notice the alleged fugitive had of his peril was given him by a blow on the head, sometimes with a club or stick of wood… In Columbia, Penn., March, 1852, a colored person named William Smith was seized as a fugitive by a Baltimore police officer, while working in a lumber yard, and, attempting to escape the officer drew a pistol and shot him dead.62

While countless residential buildings associated with slaveholders, and certain resistance by enslaved people, in the Baltimore region are still standing, there are fewer examples of sites associated with the Underground Railroad and the reaction that movement sparked. The Baltimore Jail (B-5315), designed by local architects James and Thomas Dixon and completed in 1849, is one of these few extant examples in Baltimore of a site associated with the detention of escaped slaves and abolitionists. Up until 1864, the jail held hundreds of “runaways” along with Marylanders, both white and free Black people, who assisted enslaved people as they fled to freedom. The Warden’s House from the original jail complex still stands intact on East Madison Street though the remainder of the original complex was completely transformed in the 1960s. The Warden’s House was one part of the penal system for slavery in Baltimore that also included a number of private slave jails operated around the Baltimore Harbor, although none of the private slave jails survive.63

Emancipation and the Civil War: 1861–1865

The Civil War brought about radical changes for free and enslaved Black Baltimoreans from the onset of the conflict to the end of slavery in Maryland in November 1864. From the start of the Civil War in April 1861, free Black workers in Baltimore provided support to Union troops at camps and hospitals around the city. Northern troops at Union camps became potential allies who could offer refuge and assistance for enslaved Marylanders seeking escape. On April 16, 1862, the emancipation of enslaved people in Washington, DC, created new opportunities for enslaved Black people to escape from bondage, especially in the Maryland counties adjoining the District. President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, declaring the end of slavery and the abolition of enslaved people in all Confederate states, including neighboring Virginia. Despite Maryland’s large enslaved population, the state’s official support for the Union meant the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply.

Black Baltimoreans helped to ensure the end of slavery by pouring even more effort into supporting the escape of enslaved people. Historian Lawrence Mamiya describes how George A. Hackett, a local business owner and member of Bethel A.M.E. Church, would frequently “hire a wagon, go on a plantation, fill it with slaves, and with a six-barreled revolver in each hand, defy the master to prevent it.”64 At the same time, a Congressional bill to provide “compensated emancipation” in Maryland failed in 1863 and a similar bill failed before the state assembly.65 By the spring of 1863, the Union Army began to recruit free and enslaved Black Marylanders for enlistment in the US Colored Troops. The Union army ultimately enlisted over 8,700 Black men in six Maryland regiments.66

In November 1864, Maryland passed a new state constitution abolishing slavery. The new constitution also disenfranchised white Marylanders who had left the state to fight for or live in the Confederacy and men who had supported the Confederacy within the state. Under this arrangement, the Maryland legislature approved the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution abolishing slavery nationwide on February 3, 1865.67 However, with the restoration of voting rights for many Confederate sympathizers and veterans after the end of the Civil War in 1865, the state legislature voted against the Fourteenth Amendment, guaranteeing the rights of citizens and other persons, on March 23, 1867.

That same year, former slaveholders also attempted to roll back the emancipation of the state’s formerly enslaved people using a regressive “apprenticeship” law but the US Supreme Court issued the decision In Re Turner that overturned the law.68 Three years later, the state rejected the Fifteenth Amendment, protecting a citizen’s right to vote from restrictions based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” on February 26, 1870.69 The rights and freedoms of Maryland’s Black citizens were far from assured.

Protecting Freedom after the Civil War

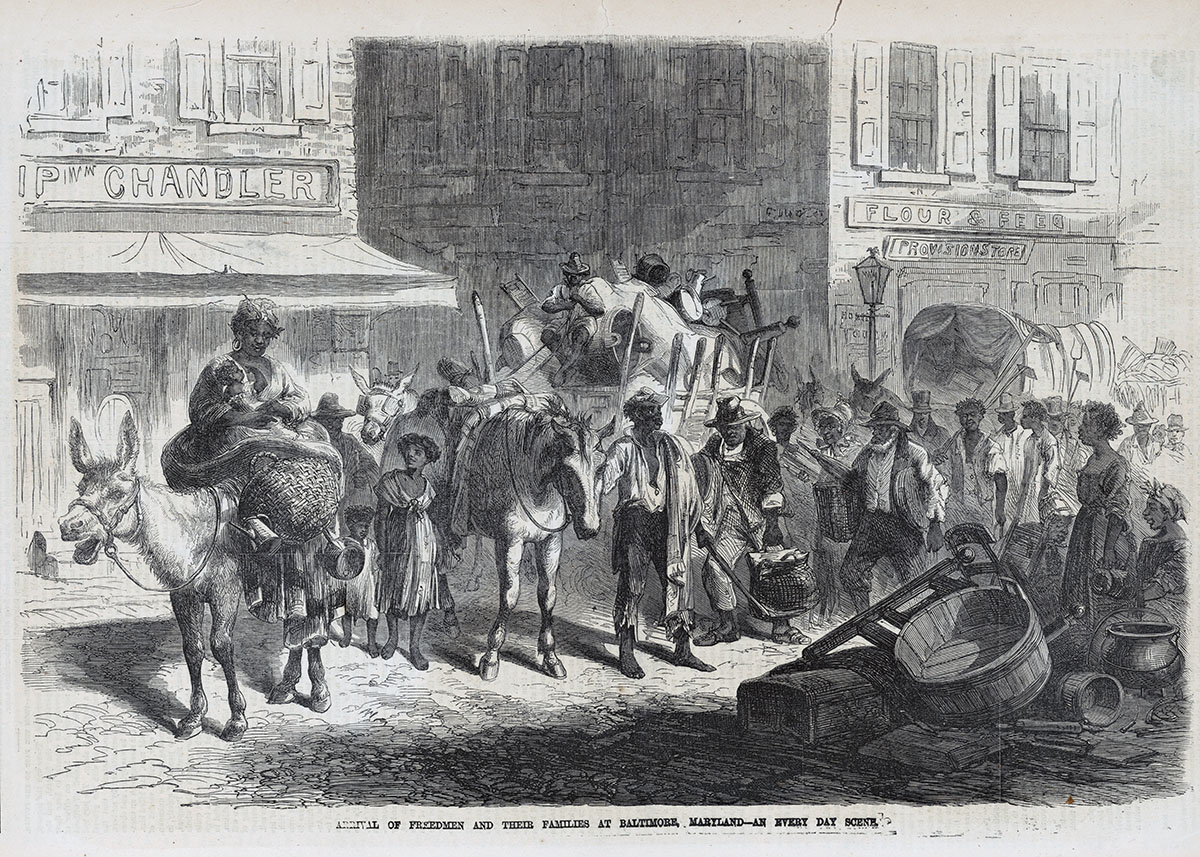

After decades of slower growth before the Civil War, Baltimore’s Black population grew quickly between 1870 and 1900—from 39,558 in 1870 to 53,716 in 1880 to 79,739 in 1900.70 Much of this growth was fueled by thousands of formerly enslaved Black people who moved from rural counties in Maryland and Virginia to Baltimore both to seek work and find protection from white violence, which was a particularly serious threat for rural Black communities during this period. In his book Imperfect Equality, historian Richard Paul Fuke describes several racially motivated violent incidents, including an attack on Black worshippers at a Methodist camp meeting in Anne Arundel County in August 1866 and a large fight disrupting an educational meeting, sponsored by the Freedmen’s Bureau of the Baltimore Association, in Queen Anne’s County on August 1, 1877. Fuke highlights the special vulnerability of “uniformed and armed blacks returning to rural Maryland” after service in the US Colored Troops to attacks by groups of former Confederate soldiers.71

Black Americans gained new rights after the Civil War through the passage of several federal civil rights acts, only to see these rights slowly eroded by the end of the nineteenth century. In Baltimore City, Black men could vote in local and federal elections for the first time since the state legislature stripped the right to vote from free people of color in 1810. In 1867, the state legislature first considered a law to allow Black men to serve on juries for crimes involving white defendants, a right that was ultimately granted in 1880 as a result of the US Supreme Court ruling in Strauder v. West Virginia.72

A few areas of Black residential and commercial life in Baltimore developed into distinct neighborhoods including Courtland Street near downtown, Orchard Street in west Baltimore, and Hughes Street in South Baltimore. These areas contained spaces for Black mutual support and public life beyond churches. New institutions, both secular and religious, opened in adapted or purpose-built structures. Abolitionist and Bethel A.M.E. Church member George Hackett helped found the Douglass Institute in spring 1865 in the former Newton University building located at 210 E. Lexington Street. The organization’s goals were to “promote education for African Americans and to provide meeting space for members of the black community.”73 A few years later, in 1867, Hackett helped established the Gregory Aged Women’s Home, also known as the Colored Women's Home, in the former Hicks Hospital—a federal military hospital established on Townsend Street (renamed Lafayette Avenue in 1869) in the vicinity of the former city almshouse. Ann Prout, a Sunday school teacher and congregant at Bethel A.M.E., became president of the association in charge of the Women’s Home.74

Many of the new migrants struggled to find housing in the immediate post–Civil War period. Fuke quotes a report by the Friends Association less than a month after emancipation in Maryland stating that the organization has been receiving “many calls from women with children… who have neither food nor shelter.” In January 1865, the group reported, “We find more suffering than we are able to alleviate. They [are in] want of the most necessary food and clothing, and have crowded into alleys and cellars.”75

Neighborhoods largely populated by Black residents grew around the harbor. Hundreds of dwellings in the Fell’s Point (B-3714), Federal Hill (B-3713), and Mount Vernon (B-3722) National Register Historic Districts were at one point occupied by free and enslaved Black people before and after the Civil War. Notable among these neighborhoods is Sharp Leadenhall (B-1369), a small area of a larger South Baltimore Black community that was substantially displaced by industrial urban renewal projects and highway construction in the mid-twentieth century. The area is now protected as a local historic district.

Politics after the Fifteenth Amendment: 1870s–1880s

The ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the US Constitution in 1870 added 39,000 new Black voters to the total of 131,000 white voters registered in the state of Maryland. This change set the stage for decades of struggle within and between the Democratic and Republican parties and encouraged the development of a new political freedom movement that sought to influence the positions of white candidates and run Black residents for local and statewide elected office. Despite new political power and overwhelming Black support for Republican candidates, the Democratic Party won the Maryland Governor’s office in every election from 1866 to 1896. Similarly, the Mayor of Baltimore remained in the grip of the Democratic Party (or a related party) from Mayor Robert T. Banks, the first mayor elected under the new State Constitution adopted in 1867, up until the election of Republican Alcaeus Hooper in 1895.

The Democratic Party’s firm political control on Baltimore and Maryland reflected the same national trends that led to the withdrawal of Union troops from the South and the end of Reconstruction. The National Historic Landmark Civil Rights Framework notes how, little more than 15 years after the end of the Civil War, “the concept of equal rights collapsed in the wake of legislative and judicial actions,” continuing:

The Republican and Democratic parties sacrificed civil rights in exchange for white southern votes. In the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, the US Supreme Court found the statutory guarantee of equal enjoyment of public accommodations unconstitutional on the grounds that the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment only applied to state activities and did not permit federal control of individual actions. This decision greatly limited the rights of blacks and strengthened Jim Crow laws in the South.76

The failure of the Republican Party to support the interests of Black Baltimoreans led many to begin organizing new independent organizations. In February 1880, for example, a convention of “colored delegates from each ward of the city” met at the Douglass Institute on Lexington Street to organize a new “Equal-Rights League.” The meeting attendees heard speeches from Rev. John A. Handy, James Taylor, N.C.M. Groome, Isaac Myers and Jeremiah Haralson. Myers observed how in Maryland:

Colored men cannot sit upon juries, colored children cannot be taught in the public schools by teachers of their own race, and colored people cannot get accommodations in hotels nor be admitted to practice as lawyers in State courts. By units of action the colored people will secure these rights and privileges.77

Haralson, a former Congressman from Alabama, spoke to Black Baltimoreans about the violent takeover of local and state governments in many Southern states. Haralson himself was forced by an armed mob to flee Alabama in 1878 and suggested that the “colored people in Maryland are free compared with their race in Alabama and the far South, where they are now fleeing from ‘a second slavery that is more damnable than the first.’” The discussion continued past midnight before the meeting concluded with a resolution:

They set forth that neither the republican nor democratic parties in this State accord equal rights to the colored man, and the organization is promoted to secure him his rights and the respect to which he is entitled as a citizen.78

Black Marylanders approached the end of the nineteenth century with a clear picture of the threats they faced and a deep commitment to continue fighting for change.

Equal Protection after the Fourteenth Amendment: 1860s–1880s

In Baltimore, new federal civil rights laws, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, provided a new foundation for Black residents and visitors to make legal and social demands for equal access and opportunity. In one significant example from February 1871, John W. Fields, a Black barber visiting Baltimore from Virginia, was ejected from a Baltimore streetcar. Fields sued and won a judgment against the trolley company, a decision that forced the integration of municipal transit in Baltimore.79

In 1867, the state legislature first considered a law to allow Black men to serve on juries for crimes involving white defendants, and finally, in 1880, the US Supreme Court decision in Strauder v. West Virginia overturned Maryland’s prohibition on Black jurors.80 In Baltimore City, Black men could vote in local and federal elections for the first time since the state legislature stripped the right to vote from free people of color in 1810. Black leadership played an important role in enabling further activism, as African Americans in Baltimore could legally hire Black lawyers beginning in 1885, the date that Everett J. Waring was admitted to practice law in Baltimore.

Equal treatment in areas of employment and criminal injustice were similarly hard fought in the 1860s and 1870s. Discrimination against Black workers had been on the rise even before the Civil War. Historian Douglas Bristol noted how, in the 1850s, white men crowded out Black barbers in Baltimore:

The last decade before the Civil War transformed barbering in the United States, as the number of white men in the trade surpassed the number of black men… In Baltimore, white men achieved a razor-thin majority within the trade at the end of the 1850s, and the number of black barbers shrank.81

Violent attacks by white workers and racialized labor strikes were another tool that white workers used to exclude or discriminate against Black workers. In 1865, white caulkers went on strike to exclude Black caulkers from the shipyards. When the strikers won, Isaac Myers, George Hackett, William F. Taylor, John W. Locks and Causemen Gaines, all laymen at Bethel A.M.E. Church, organized the cooperative Chesapeake and Marine Railway and Drydock Company in February 1866. This black-owned business eventually employed 300 skilled Black workers. Isaac Myers went on to organize the Colored Caulkers Trade Union Society in 1868. In 1869, after white workers excluded Black workers from the new National Labor Union, Myers organized the Colored National Labor Union. The Chesapeake and Marine Railway and Drydock Company lasted until 1884 and is memorialized today at the Frederick Douglass–Isaac Myers Maritime Park in Fell’s Point.82

In the struggle for equal protection, police violence remained a source of significant concern for Black households after the Civil War. Fuke noted the “fatal police shooting of Eliza Taylor, a Black woman, in September 1867,” quoting the Baltimore American:

A colored woman was killed under circumstances which show the spirit of hate and oppression cherished toward that portion of the population by many of the police.83

The police officer involved in the shooting was acquitted of murder—prompting criticism from a convention of Black leaders in Baltimore, as the Baltimore American reported:

The President [George A. Hackett] stated the object of the meeting, quoting the Declaration of Independence in proof of the fact that the colored people have no friends in Baltimore in the Governor or the police, and cited the action of the Grand Jury in discharging the Policeman Frey, charged with the murder of the colored woman, Eliza Taylor, as a specimen of the justice which is meted out to colored people in this city.84

Despite such resistance, the conditions of unequal treatment continued to get worse in Maryland and throughout the country. In 1884, the Maryland Legislature reaffirmed its opposition to interracial marriage. At the national level, efforts to disenfranchise Black voters won support from the US Supreme Court decision in The Civil Rights Cases (1883), a consolidation of five similar cases, which ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional. At the federal level, Democrats in the US Congress led in part by Maryland Senator and Bourbon Democrat Arthur Pue Gorman, defeated the Lodge Force Bill that would have authorized the federal government to ensure fair elections.

Opening Schools for Black Baltimoreans: 1860s–1880s

The beginning of the Civil War in 1861 and emancipation in Maryland in 1864 transformed the landscape of Black education in Baltimore. In 1864, a group of 30 white businessmen, lawyers and ministers, mostly Quakers, formed the Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of Colored People with the goal of establishing a Black public-school system. Within a year, the group had established seven schools in Baltimore with 3,000 students enrolled. At its peak in 1867, the group had set up more than 100 schools in the city and on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.85 In 1865, the Baltimore Normal School was founded to begin training Black teachers.

Across the state of Maryland, the Freedmen’s Bureau was critical in supporting the growth of Black schools and efforts to end the post–Civil War practice of re-enslaving Black children through forced apprenticeships. The Freedmen’s Bureau was a federal agency established in 1865 as part of larger Reconstruction efforts throughout the south. The Bureau was to assist newly freed slaves by providing educational opportunities and legal and economic advocacy to assist them in successfully gaining their independence. The Bureau’s Maryland headquarters was located at 12 N. Calvert Street in Baltimore—a building owned by Maryland Senator Reverdy Johnson.86 Historian W. A. Low described how the Bureau helped force the state government to recognize the end of slavery opening a way, “for the attainment of rights, privileges, and responsibilities that go along with the acquisition of freedom.”87

Immediately after the end of the Civil War, Black Baltimoreans and their allies focused on the need to establish schools for Black students and to create opportunities for Black educators. In 1865, the Friends’ Association opened an elementary school in the “African Baptist Church” at the corner of Calvert and Saratoga Streets.88 Around the same time at Sharp Street Church, the Centenary Bible Institute began holding classes before moving to 44 E. Saratoga Street in 1872. The Institute, which developed into today’s Morgan State University (B-5285), graduated its first student in 1878—John H. Griffin. Crowded conditions soon forced the Institute to relocate, and, in 1881, the school moved to the corner of Edmondson and Fulton Avenues in west Baltimore.89

After Baltimore City took over the Black schools established by Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of the Colored People in 1865, the school board moved to fire Black teachers, and by 1875 the city’s segregated Black schools employed no Black educators. Local congregations held “indignation meetings” between December 5 and December 8, 1879, to protest the ongoing issue and, again on January 6, 1881, to protest the school board’s refusal to honor their own pledge to hire Black teachers by the first of the year.90 Persistent demands by Baltimore’s Black residents before Baltimore City school officials finally led to the creation of the Colored High School in 1882 at Holliday and Lexington Streets.91 Protests over the exclusion of Black teachers continued up until Roberta Sheridan was hired to teach at Waverly Colored Public School in the fall of 1888.

-

Patrick H. Breen, "Nat Turner's Revolt (1831)," Encyclopedia Virginia (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 2018). ↩

-

Edward Otis Hinkley, The Constitution of the State of Maryland. Reported and Adopted by the Convention of Delegates Assembled at the City of Annapolis, April 27th, 1864, and Submitted to and Ratified by the People on the 12th and 13th Days of October, 1864. With Marginal Notes and References to Acts of the General Assembly and Decisions of the Court of Appeals, and an Appendix and Index., vol. 666, Archives of Maryland (Baltimore, MD: John Murphy & Co., 1864), http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000666/html/index.html. ↩

-

Richard Paul Fuke, “The Baltimore Association for the Moral and Education Improvement of the Colored People, 1864-1870,” Maryland Historical Magazine 66, no. 4 (Winter 1971); Edward Wilson, The History of Morgan State College: A Century of Purpose in Action, 1867–1967 (New York: Vantage Press, 1975); The Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of Colored People reorganized as a normal school for training Black teachers in 1893 and came under state control in 1908. In 1914, the school was renamed the Maryland Normal and Industrial School at Bowie, and, since 1988, has operated as Bowie State University. The Centenary Biblical Institute was renamed Morgan College in 1890, became a state institute called Morgan State College in 1939. The name changed to Morgan State University when the school was granted university status in 1975. ↩

-

Seth Rockman, Scraping by: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 34. ↩

-

Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, Forging Freedom: Black Women and the Pursuit of Liberty in Antebellum Charleston (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 120. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives and University of Maryland, College Park, “A Guide to the History of Slavery in Maryland” (Annapolis: Maryland State Archives, 2007), 10. ↩

-

Ibid., 10. ↩

-

Rockman, Scraping By, 65. ↩

-

Christopher Phillips, Freedom’s Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790–1860 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 104–5. City code required alleys to be no wider than 12 feet. ↩

-

Myers, Forging Freedom, 120, 138. ↩

-

Lawrence H. Mamiya, “A Social History of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore: The House of God and the Struggle for Freedom,” in Portraits of Twelve Religious Communities, ed. James P. Wind and James W. Lewis, vol. 1, American Congregations (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 239–40. ↩

-

Camille Heung, “Myers, Isaac (1835-1891) | the Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed,” BlackPast.org (http://www.blackpast.org/aah/myers-isaac-1835-1891); Bettye C. Thomas, “A Nineteenth Century Black Operated Shipyard, 1866–1884: Reflections Upon Its Inception and Ownership,” The Journal of Negro History 59, no. 1 (January 1974): 1–12, doi:10.2307/2717136. ↩

-

Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), 34. ↩

-

T. Stephen Whitman, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early National Maryland (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2015), 164. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives and University of Maryland, College Park, “A Guide to the History of Slavery in Maryland,” 10. ↩

-

Howard S. Baum, Brown in Baltimore (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011), 25. ↩

-

T. Stephen Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake: Black and White Resistance to Human Bondage, 17751865 (Baltimore, MD: The Maryland Historical Society, 2006), 120. ↩

-

Sarah Katz, “Rumors of Rebellion: Fear of a Slave Uprising in Post–Nat Turner Baltimore,” Maryland Historical Magazine 89, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 329. ↩

-

Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake, 128. ↩

-

“An Act Relating to Free Negroes and Slaves,” March 1832; “An Act Regulating the Admission of Attorneys to Practice Law in the Several Courts of This State,” March 1832, which restricted the right to become a lawyer in Maryland to white men; Jeffrey Richardson Brackett, The Negro in Maryland: A Study of the Institution of Slavery (Baltimore, MD: N. Murray, publication agent, Johns Hopkins University, 1889), 236–38. ↩

-

Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake, 128; Phillips, Freedom’s Port, 191–95. ↩

-

Ibid., 103. ↩

-

Carter Godwin Woodson, The History of the Negro Church (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1921). ↩

-

J. Gordon Melton, “African American Methodism in the M. E. Tradition: The Case of Sharp Street (Baltimore),” The North Star 8, no. 2; Dorothy M. Dougherty, “Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church and Community House,” Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form B-2963 (Crownsville, MD: Maryland Historical Trust, 1978 and 1981), 8.1–3. ↩

-

Ibid., 18. ↩

-

Mamiya, “A Social History of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore,” 230. ↩

-

Ibid., 240. ↩

-

Christopher William Phillips, “"Negroes and Other Slaves": The African-American Community of Baltimore, 1790–1860” (Athens: PhD diss., University of Georgia, 1992), 7. ↩

-

Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake, 135. ↩

-

Diane Batts Morrow, Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time: The Oblate Sisters of Providence, 1828–1860 (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 139; Diane Batts Morrow, “The Oblate Sisters of Providence: Issues of Black and Female Agency in Their Antebellum Experience, 1828–1860” (PhD diss., University of Georgia, 1996). ↩

-

Morrow, Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time, 16. ↩

-

Ibid., 139. ↩

-

Christopher Phillips, Freedom’s Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 128–129. ↩

-

Ibid., 131–133; Rachel Gallaher, “Coker, Daniel (1780-1846),” The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed, accessed October 9, 2018, https://blackpast.org/aah/coker-daniel-1780-1846; “William Watkins (b. circa 1803 - d. circa 1858), MSA SC 5496-002535,” Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), July 8, 2011, http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc5400/sc5496/002500/002535/html/002535.html. ↩

-

Baum, Brown in Baltimore, 25–26; Bettye Gardner, “Ante-Bellum Black Education in Baltimore,” Maryland Historical Magazine 71, no. 3 (1976). ↩

-

Davis, A Narrative of the Life of Rev. Noah Davis, a Colored Man; Hilary J. Moss, “Education’s Enclave: Baltimore, Maryland,” in Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 63–124. ↩

-

Barbara Jeanne Fields, Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 39. ↩

-

Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake, 148. ↩

-

P. Gabrielle Foreman, Sarah Patterson, and Jim Casey, “Introduction to the Colored Conventions Movement,” Colored Conventions Project: Bringing Nineteenth-Century Black Organizing to Digital Life, accessed November 6, 2018, http://coloredconventions.org/introduction-to-movement. ↩

-

Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake, 143. ↩

-

P. Gabrielle Foreman and Colored Conventions Project Team, “Colored Conventions: Bringing Nineteenth-Century Black Organizing to Digital Life” (http://coloredconventions.org/, 2016). ↩

-

“An Act Relating to the People of Color in This State.” March 1832; Maryland State Archives, “Maryland State Colonization Society Overview,” 2012, 1. ↩

-

Phillips, Freedom’s Port, 226. ↩

-

C. Peter Ripley, The Black Abolitionist Papers: Canada, 1830-1865, vol. 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 234. ↩

-

“Maryland State Colonization Convention,” The Sun, June 1841, 1. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives, “Maryland State Colonization Society Overview,” 3. ↩

-

Phillips, Freedom’s Port, 226. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives, “Maryland State Colonization Society Overview,” 3–4. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives and University of Maryland, College Park, “A Guide to the History of Slavery in Maryland,” 12. ↩

-

Robert J. Brugger, Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634–1980 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 167. ↩

-

John Shoemaker Tyson and Citizen of Baltimore, Life of Elisha Tyson, the Philanthropist (Baltimore: Printed by B. Lundy, 1825). ↩

-

Phillips, Freedom’s Port, 16–26. ↩

-

E.H.T. Traceries, “African American Historic Survey Districts - Baltimore County,” (Baltimore County Government, April 2016), http://www.baltimorecountymd.gov/Agencies/planning/historic_preservation/maps_and_research_links/historicsurveydistricts.html. ↩

-

Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake, 115-120; Lundy had established his newspaper in January 1821 in Mount Pleasant, Ohio, after purchasing The Emancipator from Elihu Embree. ↩

-

William Still, The Underground Rail Road: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &C., Narrating the Hardships, Hair-Breadth Escapes, and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom, as Related by Themselves and Others or Witnessed by the Author : Together with Sketches of Some of the Largest Stockholders and Most Liberal Aiders and Advisers of the Road (Porter & Coates, 1872), 136. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives, “Flight to Freedom: Slavery and the Underground Railroad in Maryland” (http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdslavery/html/antebellum/ba.html, December 2010). ↩

-

Maryland Public Television, “Pathways to Freedom | Underground Railroad Library | Museums and Historical Sites” (http://pathways.thinkport.org/library/sites4.cfm, 2002). ↩

-

Katz, “Rumors of Rebellion,” 330–31. ↩

-

Joseph C. Lovejoy, Memoir of Rev. Charles T. Torrey Who Died in the Penitentiary of Maryland, Where He Was Confined for Showing Mercy to the Poor (Boston: J.P. Jewett & Co., 1847). ↩

-

Whitman, Challenging Slavery in the Chesapeake, 172–73. ↩

-

Talbot Anne Kuhn, “Maryland and the Moderate Conundrum: Free Black Policy in an Antebellum Border State” (Master’s thesis, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 2015). ↩

-

William T. Alexander, History of the Colored Race in America. (Kansas City, MO: Palmetto Pub. Co., 1887), 208. ↩

-

The history of Baltimore Jail and slavery is discussed in greater detail in the Explore Baltimore Heritage on the Warden’s House on Madison Street. ↩

-

Mamiya, “A Social History of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore,” 240–41. ↩

-

W. A. Low, “The Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights in Maryland,” The Journal of Negro History 37, no. 3 (July 1952): 221–47, doi:10.2307/2715492. ↩

-

Charles W. Mitchell, Maryland Voices of the Civil War (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 357–364, 400–434. ↩

-

The Thirteenth Amendment took effect on December 18, 1865. ↩

-

Charles Olmsted, “In Re Turner (1867),” Legal History Publications, January 2005. ↩

-

The Fourteenth Amendment took effect on July 9, 1868, and the Fifteenth Amendment on March 30, 1870. The Maryland State Legislature voted to ratify both amendments nearly a century after they came into effect: April 4, 1959, for the Fourteenth and May 7, 1973, for the Fifteenth. ↩

-

US Census, 1870; 1880; 1900; These figures, based on the US Census, likely understate the true scale of Baltimore’s growing Black community. Fuke looked at the growth in Black households listed in Woods’ City Directory, noting that “the number of black householders listed… tripled from 4,000 to 12,000” between 1864 and 1871 (112). ↩

-

Richard Paul Fuke, Imperfect Equality: African Americans and the Confines of White Racial Attitudes in Post-Emancipation Maryland (New York: Fordham University Press, 1999), 206–7. ↩

-

“The Admission of Negroes as Witnesses,” The Sun, January 25, 1867. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives, “210 East Lexington: The Douglass Institute,” The African American Community and Historic Sites in Baltimore, December 1994, https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/stagser/s1259/121/6050/html/0006.html. ↩

-

Maryland State Archives, “210 East Lexington: The Douglass Institute,” The African American Community and Historic Sites in Baltimore, December 1994, https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/stagser/s1259/121/6050/html/0006.html. “Local Matters: Dedication of the Gregory Aged (Colored) Women’s Home,” The Sun, July 22, 1867. Mamiya, “A Social History of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore,” 241–42. ↩

-

Fuke, Imperfect Equality, 115. ↩

-

National Historic Landmarks Program, “Civil Rights in America: A Framework for Identifying Significant Sites” (Washington, DC: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, 2008), 7. ↩

-

“Equal-Rights League–Demands of a Colored Convention,” The Sun, February 1880, 4. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

David S. Bogen, “Precursors of Rosa Parks: Maryland Transportation Cases Between the Civil War and the Beginning of World War I,” Maryland Law Review 63, no. 4 (2004), 733. ↩

-

“Admitted to The Bar. Decision in the Wilson Case,” The Sun, March 20, 1885. ↩

-

Douglas W. Bristol Jr., Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 103–4. ↩

-

Thomas, “A Nineteenth Century Black Operated Shipyard, 1866-1884”; Frank Towers, “Job Busting at Baltimore Shipyards: Racial Violence in the Civil War-Era South,” The Journal of Southern History 66, no. 2 (May 2000): 221–56, doi:10.2307/2587658. ↩

-

Fuke, Imperfect Equality, 131. ↩

-

Ibid., 131. ↩

-

Baum, Brown in Baltimore, 25–26. ↩

-

Low, “The Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights in Maryland,” 226; Fuke, Imperfect Equality, 117. ↩

-

W. A. Low, “The Freedmen’s Bureau and Education in Maryland,” Maryland Historical Magazine 47, no. 1 (March 1952); Low, “The Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights in Maryland,” 247. ↩

-

Angela D. Johnson, “The Strayer Survey and the Colored Schools of Baltimore City, 1923–1943” (Master’s Thesis, Morgan State University, 2012), 10. ↩

-

Ibid., 10. ↩

-

Mamiya, “A Social History of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore,” 244. ↩

-

Johnson, “The Strayer Survey and the Colored Schools of Baltimore City, 1923–1943,” 11. ↩